Book of Kells: History of world’s most famous medieval manuscript rewritten after dramatic new research

Lavishly illustrated 1,200-year-old copy of Gospels previously thought to have been thought to have been created as one book

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.New research is rewriting the history of the world’s most famous early medieval manuscript – a lavishly illustrated 1,200-year-old copy of the Gospels known today as the Book of Kells.

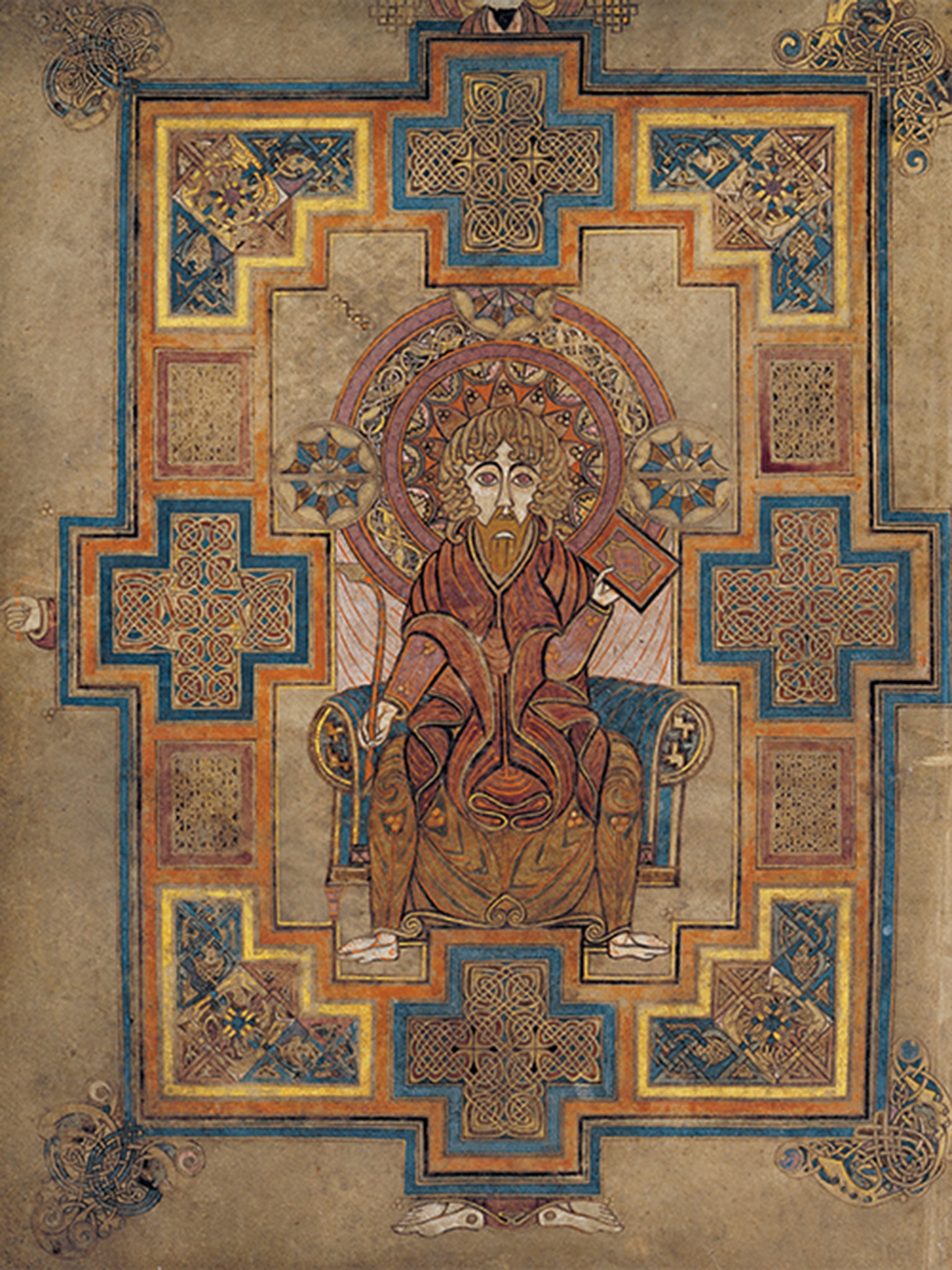

It had always been assumed that the work – which includes 150 square feet of spectacular coloured illustrations – was conceived and created as one book, containing all four Gospels.

But a detailed analysis of the texts has led a leading expert on early medieval illuminated manuscripts, Dr Bernard Meehan of Trinity College, Dublin, to conclude that the book was originally two separate works that were, in the main, created up to half a century apart.

Dr Meehan's new hypothesis suggests that the last part of the Book of Kells (namely St John’s Gospel) and the first few pages of St Mark’s Gospel were created by a potentially quite elderly scribe on the Scottish island of Iona sometime during the last quarter of the eighth century.

But he believes the rest of St Mark’s Gospel and the Kells copies of the Gospels of St Luke and St Matthew were created up to 50 years later in Ireland – in Kells itself.

It was previously thought by many that work on all four books had started on Iona and had been fairly rapidly completed in Kells, all as one continuous project.

Dr Meehan now thinks that it is more likely that the first work – St John’s Gospel – had originally been intended as a stand-alone single Gospel book .

Historical evidence suggests that, in the very late eighth century and at the beginning of the ninth, a series of political and other events disrupted Iona’s Gospel book production activity.

Their troubles started in 795 AD, when Viking raiders attacked the monastery.

it is also probable that the community was hit by some sort of major epidemic – possibly smallpox. Seven abbots at major monasteries in Ireland and western Britain all died in 801 and 802 – including two abbots (and one ex-abbot) of Iona.

A second Viking raid on the community took place in 802 and four years later, a third saw 68 monks and others were slaughtered.

Battered by the violence and the scourge of epidemic disease, much of the community decided to relocate by establishing a successor monastery in a safer place – an inland site across the sea at Kells in Ireland.

It was there that Dr Meehan believes that scribes ultimately finished off the copy of St Mark’s Gospel and set to work making their copies of St Matthew’s and St Luke’s gospels.

These, he said, were then combined with the St John’s Gospel manuscript to create the Book of Kells as it survives to this day.

Handwriting evidence suggests that the Iona monk who created his spectacular copy of St John’s Gospel was, stylistically, a very traditional scribe who had learned his craft at some stage in the mid eighth century. His scribal activity appears to have ceased abruptly, after he completed verse 26 of the fourth chapter of St Mark’s Gospel.

He may well have been one of the three very senior monks who died on Iona in 801 and 802 – either the newly appointed abbot, Bresal mac Ségéni, who died 801, or his successor Connachtach who died 802. It could also be the former abbot, Suibne who died in 801. He had resigned as head of the community 30 years earlier.

But why did that stylistically very traditional scribe decide to produce the fourth Gospel - that of St John - first rather than last? That decision potentially helps shed important light on the early history of Christianity in Ireland and Scotland.

Of the four Christian gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) only the fourth (John) was, and still is, traditionally believed to have been written by somebody who actually knew Jesus – namely, John, one of Jesus twelve most senior disciples.

His gospel was therefore privileged by some above the others in the very early Christian church. What’s more, according to tradition, John emigrated from Palestine to Ephesus (in what is now Turkey) around a decade after Jesus’ crucifixion. Traditionally, he was said to be the disciple Jesus was closest to.

At roughly the same time another disciple, St Peter, went to Rome where he became the first Pope.

Although all early Christians recognised the authority of successive popes (Peter’s successors) in Rome, some – because of John’s role in Ephesus – regarded Asia Minor (modern Turkey) as an equally key original Christian epicentre. The Irish recognised Rome as the home of the papacy – but the city’s past imperial glories had no resonance for them because Ireland had never been politically or culturally part of the Roman Empire.

Because they were less impressed by Rome’s glorious past, they were therefore more inclined to privilege John – a disciple who was not in any way associated with it.

What’s more, back in the third to seventh centuries, there had been, throughout the Christian world, ferocious disagreements as to the best way of calculating the correct date for Easter, for the anniversary date of Jesus’ resurrection. Again the Irish church’s view on that issue had been partly based on information specifically from John’s Gospel. That may have been another reason why the fourth gospel had such a special place in the hearts of Celtic Christians.

St John’s Gospel was therefore particularly relevant to Celtic Christian monks – like those on Iona.

“We know of four Celtic tradition St John’s Gospel books that survived into early modern or modern times – and I suspect that originally there must have been literally hundreds produced in the seventh and eighth centuries – an indication of just how important that particular gospel was from their perspective,” says Dr Meehan, who, through the London publishers Thames & Hudson, is this week publishing a new official guide to the Book of Kells.

Today, the great 680-page illuminated manuscript itself (now divided into four volumes) is owned by Trinity College, Dublin. It is on public display there – and every three months the pages are turned and four new pages are put on view.

This unparalleled treasure has been at Trinity for around 350 years (and for half of that time it has been on public display).

But its earlier history was substantially more dramatic. Almost 200 years after its completion, thieves stole it (and probably its gold and jewel-encrusted container) and buried the book itself under a sod of grass, almost certainly in a nearby field. Fortunately, after almost three months, its hiding place was revealed to the monks of Kells who then succeeded in retrieving it. It is not known whether the community had to pay a ransom to learn of its whereabouts.

Today, the first 10 pages and the last 12 pages of the original Gospel book are missing – and it’s very likely that they were so badly damaged by being buried in the ground, that they were disposed of after recovery, but never replaced. Indeed, on the surviving current first and last pages of the book, one can still see water damage that would be consistent with that brief, yet destructive, period of burial.

More than six centuries later, during a major Irish rebellion against English rule, Kells and its ancient abbey were partially destroyed. A few years later, the great gospel book was removed by the English to the more secure environment of the ecclesiastical authorities in Dublin. The Irish capital’s Welsh-born Anglican bishop, a fervent Protestant called Henry Jones, who had studied at Trinity and had subsequently become its vice-chancellor (but had also been Oliver Cromwell’s head of military intelligence!), then donated the book to the college, where it still resides.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments