Science news in brief: From Antarctic supernovae to crippled panthers

And other news from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Florida’s panthers hit with mysterious crippling disorder

In southwest Florida, any sighting of the state’s iconic panther – on your porch, lounging in the backyard, advancing towards you on a trail – might go viral. But last week, the state’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission took to social media to crowdsource a different kind of video: panthers that seem to have trouble walking.

Trail cameras in three counties have identified eight endangered panthers and one bobcat with a hitch in their step, affected by a mysterious neurological disorder that seems to hit kittens hardest. State officials have also confirmed nerve damage firsthand in another panther and another bobcat.

In one video shared by the agency, a panther kitten stumbles several times as it follows its mother and another sibling, dragging its lower body as it struggles to rise.

“While the number of animals exhibiting these symptoms is relatively few, we are increasing monitoring efforts to determine the full scope of the issue,” says Gil McRae, the director of the state’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute in St Petersburg, Florida.

The first video footage of a struggling kitten was taken by a citizen and sent to the agency in 2018. Later, a review of still photos from 2017 seemed to show another ailing kitten. This year the number of cases has increased. “It was not until 2019 that additional reports have been received, suggesting that this is a broader issue,” Carli Segelson, a spokeswoman for the agency, says.

This disorder is the latest obstacle to the recovery of the Florida panther, a beloved big cat and the state’s official animal. The panther is the only remaining puma population in the eastern United States, and it is a fixture on licence plates and the namesake of the Miami area’s NHL team.

In the 1990s, the Florida panther population dipped to around 20 cats, but the number rebounded with the addition of eight female pumas captured in Texas. In the past decade, however, as the Florida panther population has grown in step with human development in the animal’s habitat, scores of panthers have been killed crossing roads.

Genome study reveals clues to komodo dragon’s unique abilities

Komodo dragons are the largest lizards on the planet, with some adults measured at more than 350 pounds and longer than 10 feet. They detect their prey, including deer and water buffalo, from miles away with an exquisite sense of smell, and at close range, they race at terrifying speeds. Even a single bite can be enough to seal the prey’s fate, because a dragon’s saliva contains potent anticoagulants: once the bleeding starts, it doesn’t stop.

But when komodo dragons bite each other, which they do with some frequency, they do not bleed out the way their prey do. That suggests that at some point, they evolved a resistance to their own anticoagulants.

It’s one example of the odd batch of traits that have fascinated scientists, including Katherine Pollard, an epidemiologist and biostatistician at the University of California, San Francisco, as well as a researcher at the Gladstone Institutes. She wondered what the komodo dragons’ genome would reveal about their biology and evolution.

In a paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, she and her colleagues present the lizards’ genome, revealing evidence of a large number of mutations in important komodo genes. Their analysis offers insights into the dragons’ blood, senses and other unique aspects of their anatomy.

The group cobbled together a draft genome from two dragons living at Zoo Atlanta some years ago, and used tissue from a dragon in the Prague National Zoo to flesh it out. But more recently, Abigail Lind, a postdoctoral fellow in Pollard’s lab, focused on the process of interpreting the genome. Using algorithms that helped parse which parts of the sequence coded for proteins, Lind identified more than 18,000 genes. With the help of other lizard genomes, the researchers made predictions about the genes’ roles.

“We wanted to particularly look at different unique traits,” Pollard says. “The most obvious one is they are gigantic. But there are some other really cool things about them.”

To look for komodo genes that had undergone concerted evolution, the researchers pinpointed about 200 with a particularly large number of mutations compared to related species. This pattern suggested that natural selection had favoured alterations to those genes, honing them into a form that is specific to the dragons.

A supernova was hiding in Antarctica’s snow

Earth is continuously ploughing through extraterrestrial dust. Tens of thousands of tons of the stuff, mostly from asteroids and comets, settles all over the planet every year.

But even the faintest detritus has a story to tell. Recently, scientists analysed dust collected from Antarctic snow and found an excess of radioactive iron. After ruling out contamination from nuclear weapons testing and other sources, the team concluded that the iron was produced by supernovas, fleeting explosions of stars more massive than the sun. The results were published on 12 August in Physical Review Letters.

Meteorite hunters are drawn to Antarctica because the space rocks, which are dark, stand out against the snow. Dominik Koll, a doctoral candidate in nuclear physics at the Australian National University in Canberra, appreciates Antarctica for other reasons: its remote location and desert climate, which ensure that whatever extraterrestrial dust falls from the sky remains relatively uncontaminated and undiluted.

In 2015, a colleague of Koll’s collected roughly 1,100 pounds of snow near Kohnen Station in Antarctica. The snow, which had fallen within the past 20 years, was shipped to Germany, where it was melted and filtered. Then, with an extremely sensitive mass spectrometer, Koll and his collaborators identified the compounds within the detritus.

The researchers were looking for a rare, unstable variety of iron containing 26 protons and 34 neutrons. This radioactive isotope, iron-60, is produced by supernovas.

Iron-60 has been found on Earth in oceanic crust that is millions of years old and on the surface of the moon, indications that the isotope circulated through the solar system long ago. But iron-60 from supernovas has never been found in geologically young material; its discovery in relatively fresh snow would suggest that it’s still raining down on Earth.

The mystery of the Himalayas’ skeleton lake just got weirder

Nestled in the Indian Himalayas, some 16,500 feet above sea level, sits Roopkund Lake. One hundred and thirty feet wide, it is frozen for much of the year, a frosty pond in a lonely, snowbound valley. But on warmer days, it delivers a macabre performance, as hundreds of human skeletons, some with flesh still attached, emerge from what has become known as Skeleton Lake.

Who were these individuals, and what befell them? One leading idea was that they died simultaneously in a catastrophic event more than 1,000 years ago. An unpublished anthropological survey from several years ago studied five skeletons and estimated they were 1,200 years old.

But a new genetic analysis carried out by scientists in India, America and Germany has upended that theory. The study, which examined DNA from 38 remains, indicates that there wasn’t just one mass dumping of the dead, but several, spread over a millennium.

The report, published in Nature Communications, has led to a “far richer view into the possible histories of this site” than previous efforts provided, says Jennifer Raff, a geneticist and anthropologist at the University of Kansas who was not involved with the work.

Genetic analysis has helped make some sense of the jumble of bones. The researchers, led in part by Niraj Rai, an expert in ancient DNA at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences in India, and David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard University, extracted DNA from the remains of dozens of skeletal samples, and managed to identify 23 males and 15 females.

Based on populations living today, these individuals fit into three distinct genetic groups. Twenty-three, including males and females, had ancestries typical of contemporary South Asians; their remains were deposited at the lake between the 7th and 10th centuries, and not all at once.

Then, perhaps 1,000 years or so later, two more genetic groups suddenly appeared within the lake: one individual of East Asian-related ancestry and, curiously, 14 people of eastern Mediterranean ancestry.

The earlier study, of five skeletal samples, found three with unhealed compression fractures. In any case, across a range of centuries “it’s hard to believe that each individual died in exactly the same way,” says Éadaoin Harney, a doctoral student at Harvard and the lead author on the study.

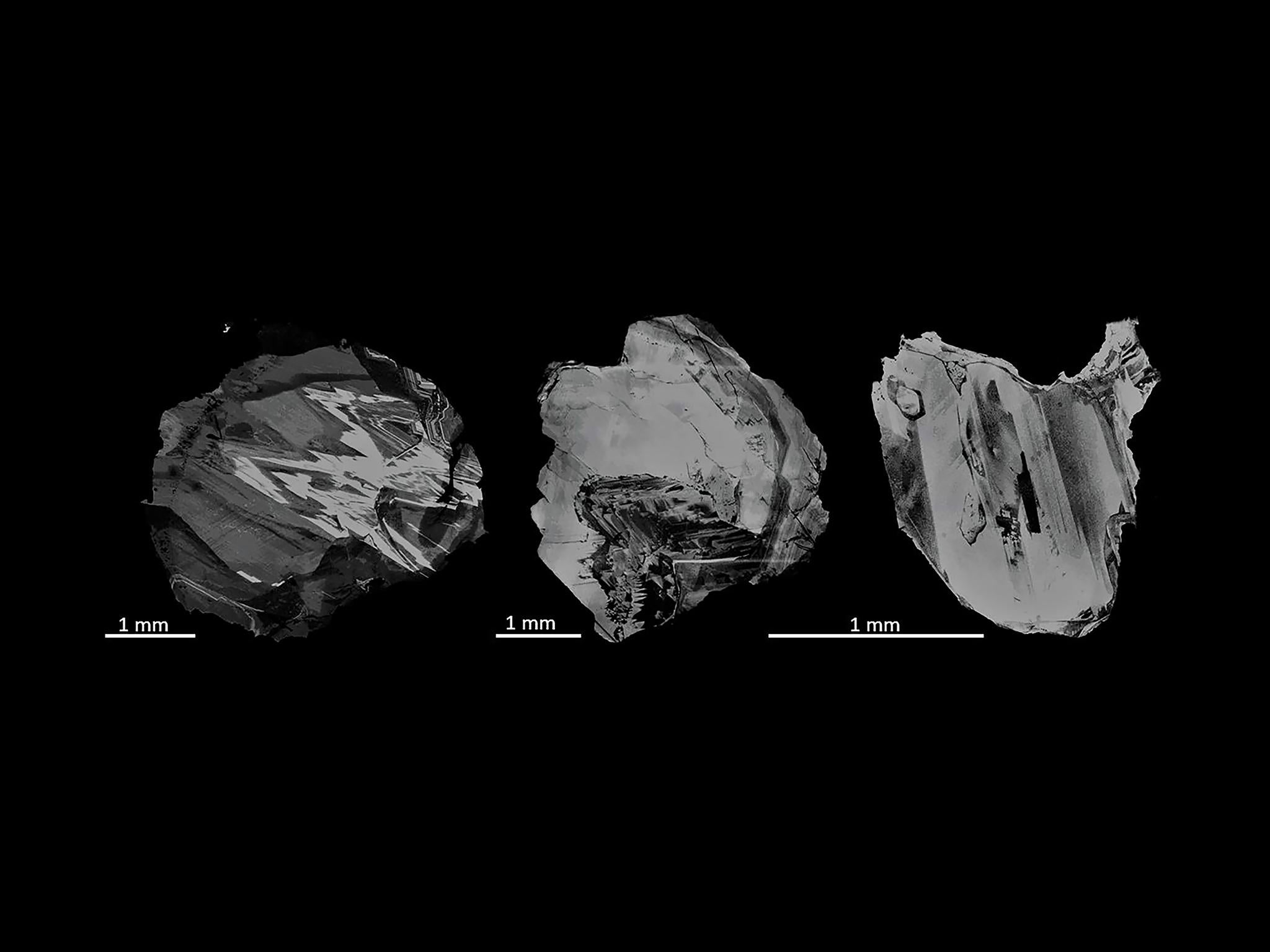

Glimmers of Earth’s distant past found in super-deep diamonds

We can’t dig to the centre of the Earth, and we can’t time travel. But if the universe could grant a consolation prize, it would be a super-deep diamond.

These sturdy, rare minerals travel hundreds of miles from Earth’s mantle, where they form, to the crust, where they are discovered. Along the way, they trap history in microscopic flaws.

“Super-deep diamonds are just time capsules, basically,” says Suzette Timmerman, a geochemist at Australian National University. She and her colleagues recently analysed a set of super-deep diamonds from Brazil and found, preserved within them, helium from Earth’s primordial past.

Their work, published in Science, is a further step towards understanding how the planet evolved since its coalescence from bits of rock and gas some 4.54 billion years ago.

Earth’s mantle, some 1,800 miles thick, begins about 25 miles down and is sandwiched between the thin outer crust and the dense, iron core. This ancient rock stuffing makes up more than three-quarters of the planet’s volume. But scientists know little about it.

Seismic studies have revealed how a convection current within the mantle allows its contents to circulate. Ocean island basalts — rocks that cooled after volcanic eruptions of magma from the mantle — have offered hints of the mantle’s chemical composition. But neither source has revealed what the mantle is made of at any particular depth.

Most diamonds form 100 miles or so below the surface. But in the region of Brazil where Timmerman worked, more than 99 per cent of diamonds are super-deep, having formed in the mantle’s transition zone, between 254 and 410 miles down.

Timmerman and her team used a high-tech laser and vacuum to release the fluid trapped in the inclusions of super-deep diamonds. Inside they found trace isotopes of helium, in ratios similar to what has been found in ocean island basalts.

Helium is extremely rare on Earth, so its presence in ocean island basalts suggested that a reservoir of helium existed somewhere below ground, although how far down was unclear.

“With ocean island basalts, we don’t know how much their chemical composition has changed when they come up,” Timmerman says. But the helium in the super-deep diamonds could have originated only where the diamonds formed, in the mantle — strong evidence that a helium reservoir exists down there.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments