The discovery of microplastics in the Antarctic fjords could have disastrous repercussions on the environment

While this plastic problem has become more prevalent, animals colonising the exposed fjords face challenging conditions which could have cascading effects on the ecosystem

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the middle of the last century, mass-produced, disposable plastic waste started washing up on shorelines and could to be found in the middle of oceans.

This has since become an increasingly serious problem, spreading globally to even the most remote places on earth. Just a few decades later, in the 1970s, scientists found the same problem was occurring at a much less visible, microscopic level, with microplastics.

These particles are between 0.05mm and 5mm in size. Larger pieces of plastic can be broken down into microplastics but these tiny bits of plastic also come from deliberate additions to all sorts of products – from toothpaste to washing power.

Now, with major global sampling efforts, it has become clear that microplastics are dispersing all over the world – in the water column, sediments, and marine animal diets – even reaching as far south as the pristine environments of Antarctica.

Glacial retreat

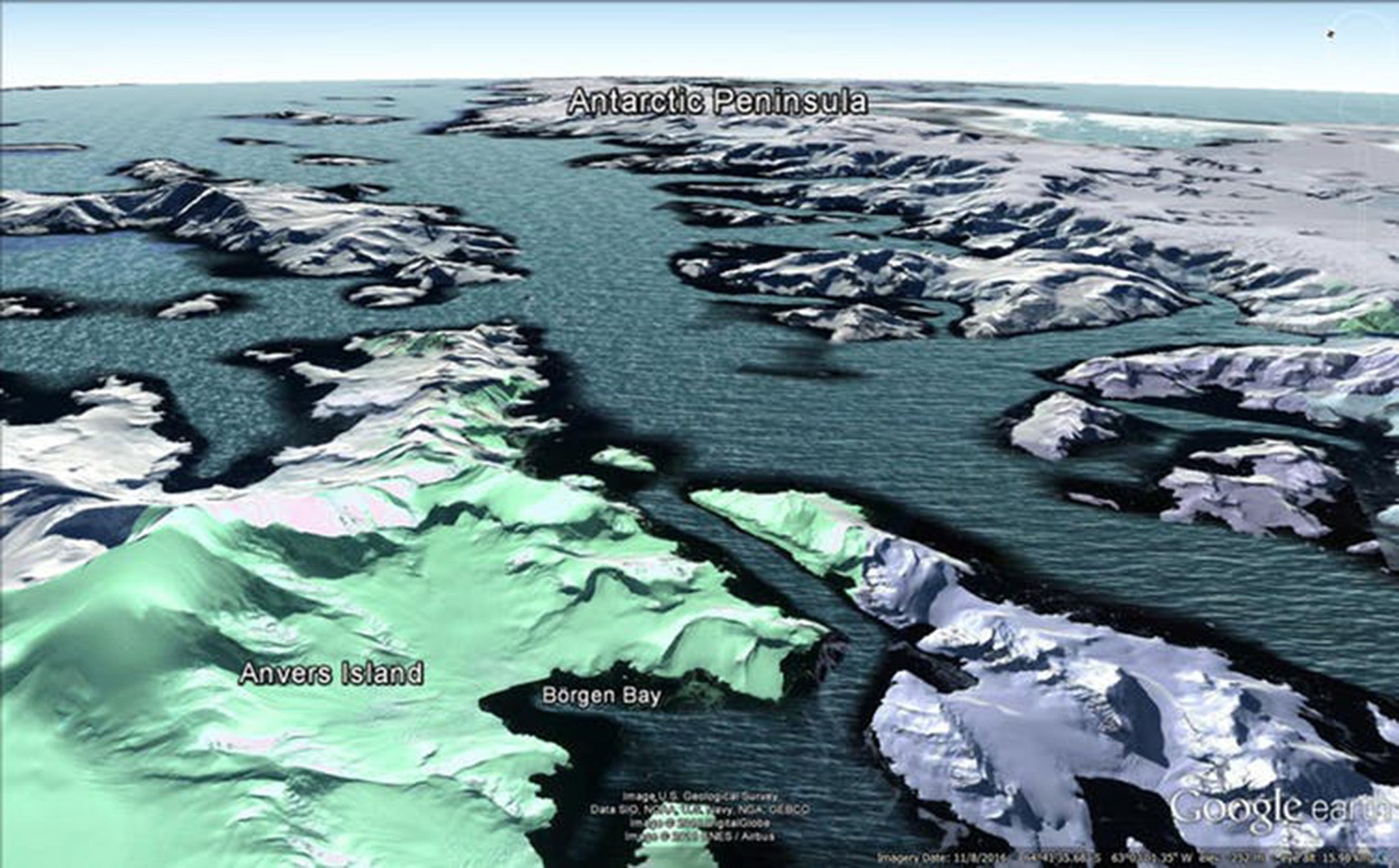

While this plastic problem has become more prevalent, one of the most pristine ecosystems on earth, the fjords of the western Antarctic Peninsula, have been revealed by retreating glaciers.

Tucked between islands and the mainland, the coast along the western Antarctic Peninsula has long, narrow inlets created by glaciers. During the last 50 years, these fjords have physically changed, due to reduced sea ice cover and because nearly 90 per cent of glaciers have retreated in this region. These processes have exposed the ocean floor of many of the fjords for the first time.

The potential for microplastics to impact this environment and its marine life is huge – and we’re now working to figure out the depth of the effect that microplastic pollution is having on the newly colonised habitats. Any microplastics recovered in the Southern Ocean, particularly in newly formed ecosystems, raise alarm. They not only indicate that the area has been affected, but that plastic pollution is increasingly ubiquitous too.

New habitats

In November 2017, our multidisciplinary UK-Chile-US-Canada research team – known as Icebergs – joined the RRS James Clark Ross (an ice strengthened research ship) and headed to Antarctica’s northernmost fjords. Our goal was, and still is, to gain a better understanding of how the environment and organisms evolve in newly emerging and colonising habitats in Antarctica. We are particularly interested in the marine ecosystems on the ocean floor, so have been looking at areas such as Marian Cove and Börgen Bay on the western Antarctic Peninsula, where communities have only developed in the last few decades – due to the retreating glaciers.

Thriving marine ecosystems can act as climate regulators. When ice retreats, new and pristine fjordic habitats are revealed and phytoplankton blooms occur. These help to counteract climate change because they take carbon dioxide gas out of the atmosphere. New productive seabed habitat also becomes available for the diverse shallow water fauna that eat this algae, and store the carbon long term. Not counteracting climate change, however, is the fact that new open water absorbs heat faster, in contrast to ice that would have reflected it.

The animals colonising the exposed fjords face challenging conditions. The sediment and fresh water flowing in the glacier melt runoff make it very difficult for many organisms to survive. And, if exposed to them, microplastics can be a serious concern for many marine animals, especially filter-feeding organisms (for example krill, and other zooplankton). As these creatures filter water to obtain food, they may ingest microplastics which can clog and block their feeding appendages, limiting food intake. Ingested microplastics may be transferred to the circulatory system too, which can cause an increased immune response.

Microplastics may also bring in new bacteria and chemical pollutants attached to them too. So, because many filter-feeding organisms support the entire food web, any impact on them should be expected to have cascading effects on the ecosystem.

In newly revealed habitats, creatures are less likely to have been impacted by marine pollutants previously so they can help us learn about more recent changes in an environment. To our knowledge, microplastics have not been found in the Antarctic fjords before now, but our preliminary results have already found an alarmingly high presence – similar to those found in the open water of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, near big civilisations.

These results came from samples taken directly from the fjords, and we are now looking further at the evidence of how micro-organisms are being affected by microplastics. During the next two Antarctic summers, we will be collecting more geophysical, physical oceanographic, sedimentological and biological data from these pristine sites in the same locations, so we can compare the changes over time in the habitats that colonise new ocean floors in Antarctic fjords.

Only after such rigorous data collection and analysis will we be able to tell the true impact of microplastics on pristine environments. Until then, we can all do our bit to cut down on potential pollution and protect what may very well be the last pristine environments on earth.

Alexis Janosik is an assistant professor of biology at the University of West Florida; ata interpretation ecologist at the British Antarctic Survey; rofessor of Physical Geography, University of Exeter; and enior lecturer in marine geology at Bangor University. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments