The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Ancient woman’s remains found in Indonesia sheds light on lost human lineage

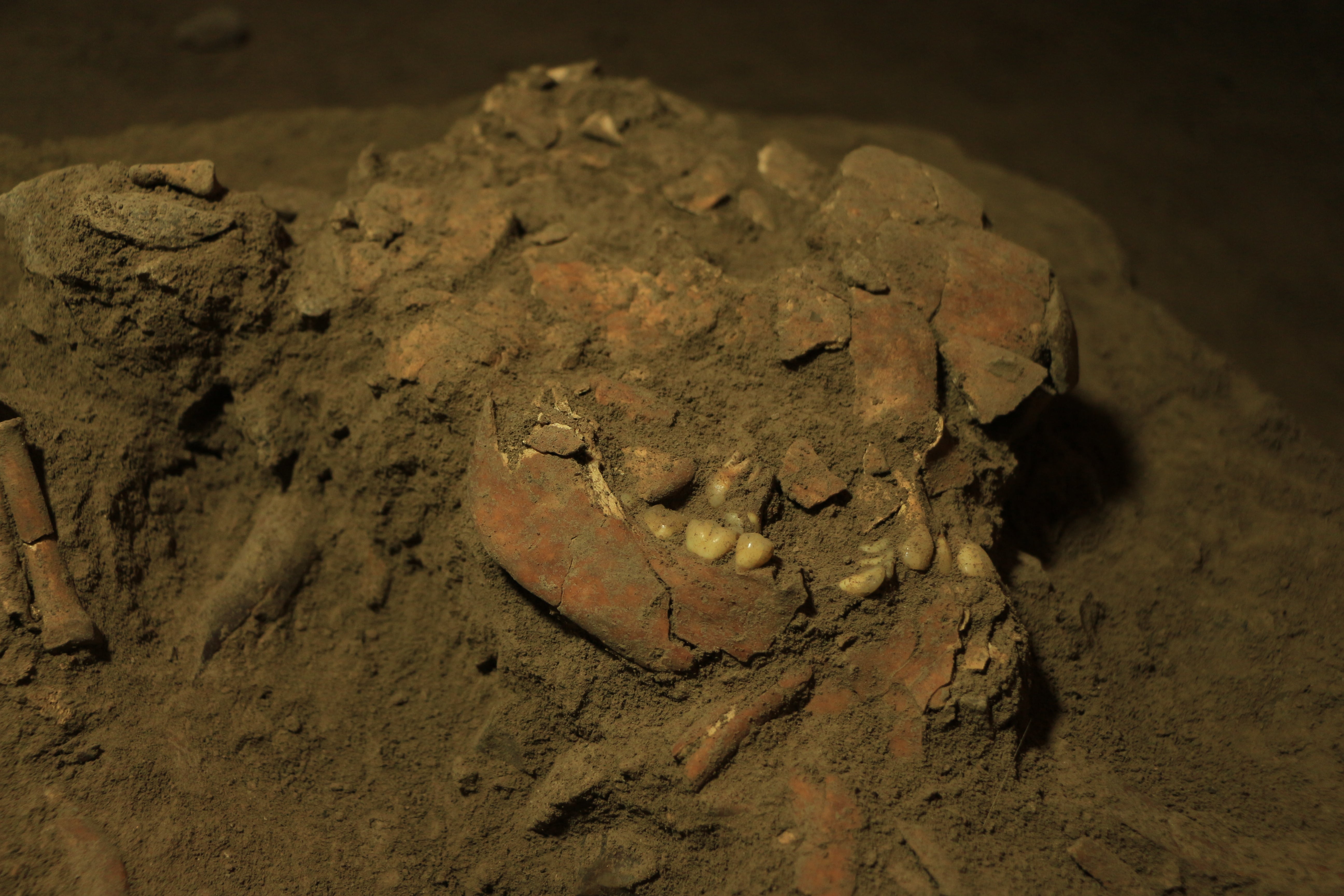

The remains of ‘Besse’, who was buried 7,200 years ago in Indonesia, have offered clues to a lost lineage of humans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A young woman, buried 7,200 years ago in the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, belonged to a lost lineage of humans who were some of the earliest settlers to leave mainland Asia, a new genetic analysis reveals.

The remains – unearthed in 2015 – belong to “Besse”, a 17- or 18-year-old woman who died about 7,200 years ago and is the only known skeleton of one of the Toalean people, the study published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, said.

The Toalean people were mysterious hunter-gatherers who mainly preyed on wild endemic pigs and harvested shellfish from the island’s creeks and estuaries, according to archaeologists, including those from Griffith University in Australia.

Archaeological records of the Toaleans, however, disappeared a few thousand years after the first late Stone Age settlements emerged on the island.

The Toaleans were related to the first modern humans who entered Wallacea some 65,000 years ago or more, according to the archaeologists, who based their findings on the collective evidence.

Wallacea was an ancient group of mainly Indonesian islands, that includes Sulawesi, Lombok and Flores, which once provided a gateway to New Guinea and Australia.

“These seafaring hunter-gatherers were the earliest inhabitants of Sahul, the supercontinent that emerged during the Pleistocene (Ice Age) when global sea levels fell, exposing a land bridge between Australia and New Guinea,” study co-author Adam Brumm from Griffith University, said in a statement.

“To reach Sahul, these pioneering humans made ocean crossings through Wallacea, but little about their journeys is known,” Dr Brumm added.

The woman’s genome also revealed she was a distant relative of present-day Aboriginal Australians and Melanesians or the Indigenous people on the islands of New Guinea and the western Pacific.

Some parts of her DNA, the scientists said, were also inherited from the now-extinct Denisovans, who were the distant cousins of Neanderthals.

Since fossils were sparse and ancient DNA is easily degraded because of the region’s tropical climate, scientists said very little was previously known about the population history of modern humans in Wallacea.

Researchers said the remains of the young woman have now offered the first ever ancient human DNA in Wallacea.

“Our team found ancient DNA that survived inside the inner ear bone of Besse, furnishing us with the first direct genetic evidence of the Toaleans,” the scientists wrote in The Conversation.

Based on the proportion of Denisovan DNA in Besse, the scientists speculate that the main meeting point between our species, the Homo Sapiens and the Denisovans may have been in Sulawesi or in the Wallacea cluster of islands.

This is similar to the evidence obtained from early human fossils in Europe of the crossover between Neanderthals and modern humans.

“The discovery of Besse and the implications of her genetic ancestry show just how little we understand about the early human story in our region and how much more there is left to uncover,” Dr Brumm said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments