Mysterious ancient humans with brains like modern people prompt rethink of early evolution

'What if we have been studying the rise of modern human behaviour, and it’s not the rise of modern human behaviour?'

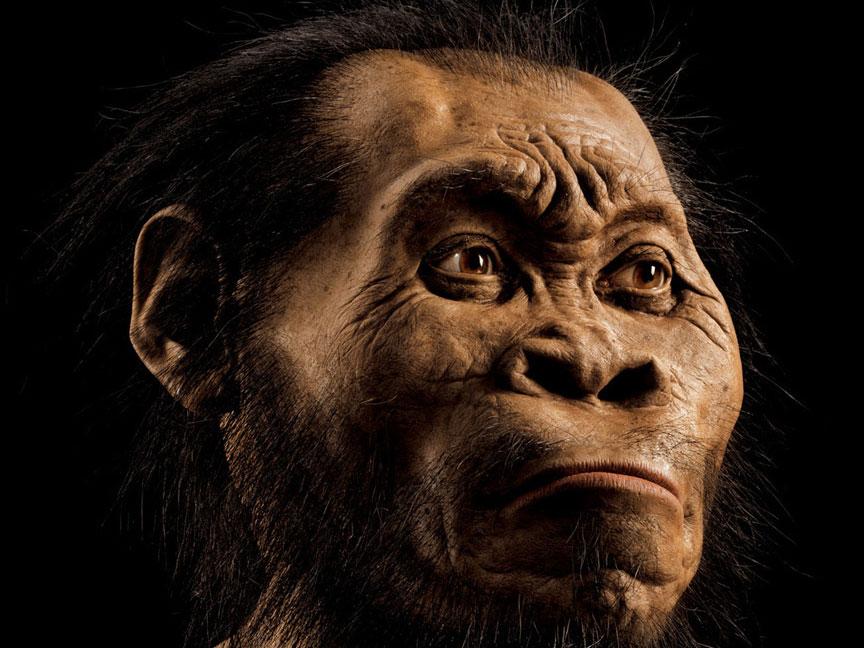

An ancient species of human with a brain no larger than an orange may have possessed intelligence to rival that of our own species.

Despite their size, the brains of Homo naledi have many of the sophisticated features found in modern humans.

The discovery has led to suggestions that long-standing beliefs about the evolution of human brains are “fundamentally wrong,” and much of Africa’s archaeology should be reconsidered.

H. naledi was revealed to the world in 2015 after at least 15 skeletons were unearthed in a South African cave. It immediately caused a stir because of its combination of primitive and advanced characteristics.

From the outset, one of the scientists behind the discovery, Dr Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand, insisted there was more to this new species than its diminutive 5-foot stature suggested.

“We argued that H. naledi was exhibiting some very complex behaviours,” he told The Independent. “We said it had a tool-making hand – or at least a potentially tool-making hand – we pointed out it had small feet and we rather controversially said the site may be a deliberate body disposal site.”

This point in particular struck a chord, as the idea these ape-like humans buried their dead in a ritualistic manner would suggest a level of sophistication never before seen in such apparently primitive creatures.

“That obviously caused some uproar in the field because of course everyone said ‘it can’t, it has got too small a brain’,” said Dr Berger.

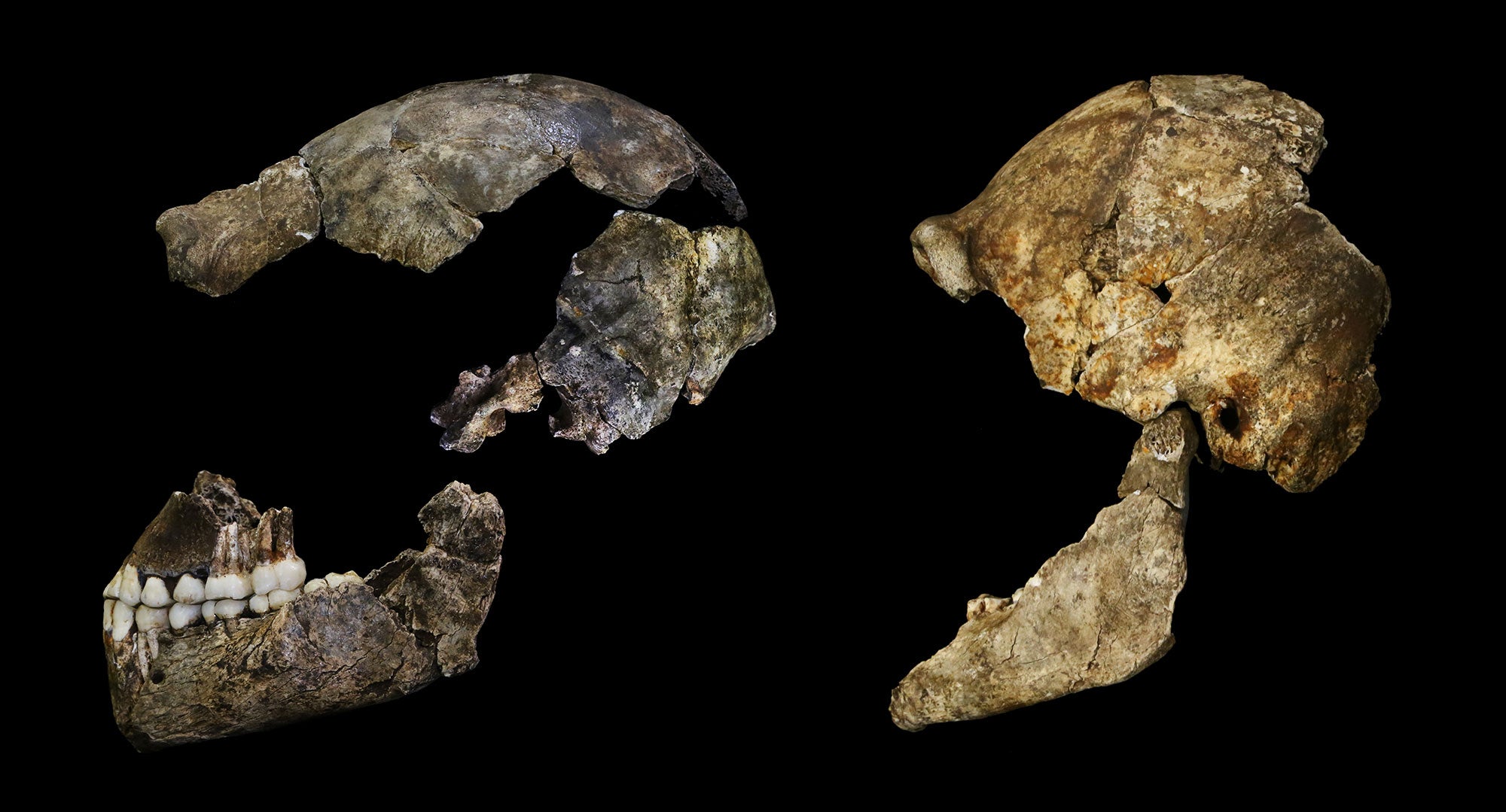

To determine whether there was more going on in the heads of these ancient humans than met the eye, Dr Berger enlisted the help of colleagues who could help him piece together skull fragments and create digital reconstructions of their skull interiors.

"This is the skull I've been waiting for my whole career," said lead author Dr Ralph Holloway, a physical anthropologist at Columbia University.

Using this technique, scientists can determine the structure of the brain, which “beats a mirror image of itself” onto the inside of the skull.

Their findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

On one level, the researchers’ reconstruction confirmed what they already knew – H. naledi had incredibly small brains comparable with primitive human-like creatures called Australopithecines.

However, when the small brains found in Australopithecines were subjected to the same analysis as H. naledi, they were found to have far more in common with chimpanzees than modern humans – as might be expected.

Whereas scans of the H. naledi revealed complexity in many areas – including regions linked with emotion and a large frontal lobe associated with language.

"It's too soon to speculate about language or communication in H. naledi," said co-author Dr Shawn Hurst of Indiana University. "But today human language relies upon this brain region."

Dr Berger added: “H. naledi has got all that, but packaged in the brain the size of a large orange. Here we have a violation of that sacred cow – the idea there was this link between ever increasing brain size paralleled with ever increasing complexity – yet you have this tiny brain which is in effect every bit as complex as a modern human.”

This is significant because it prompt a rethink about what the size of the brain means for our intelligence.

Dr Simon Underdown, an anthropologist at Oxford Brookes University who was not involved with the study, said the work was “really interesting”, although he noted the limitations of the methods used to investigate ancient human brains.

“The inherent weakness is that’s only what the outside of the brain looks like – and we know an awful lot of what goes on in our brain is internal,” he said.

However, he added: “You can look at the relative size and shape of different parts of the brain and look at what it looks like in a generic comparison ape and what it looks like in humans – and then look at where H. naledi sits”.

In 2017 geologists placed this unusual ancient human in southern Africa between 236,000 and 335,000 years ago, meaning they may have shared the region with modern humans.

Their exact relationship with humans, however, is unknown. They could be at the base of the human family tree, they could be our distant cousins, or they could – according to Dr Berger – even have hybridised with modern humans.

All of this is still highly speculative, but one of the most exciting conclusions to be drawn from this work is the challenge it poses to archaeologists trying to piece together the story of human evolution – and human intelligence.

Dr Underdown said: “The fact that it’s sitting 250,000 years ago in southern Africa where we are beginning to see in the archaeological record an explosion in complex tool use that we were attributing to modem humans – we can’t be so arrogant any more. This does open up other possibilities."

“There is always the danger when you have just got stone tools, you don’t 100 per cent know who made them because we don’t have all the fossils.”

To find out for sure, archaeologists will need to discover more evidence that directly links these archaeological sites with either our own species, H. naledi or perhaps another species entirely.

For the time being, Dr Berger said researchers cannot take for granted many of their assumptions about early humans.

”What if we have been studying the rise of modern human behaviour, and it’s not the rise of modern human behaviour?” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments