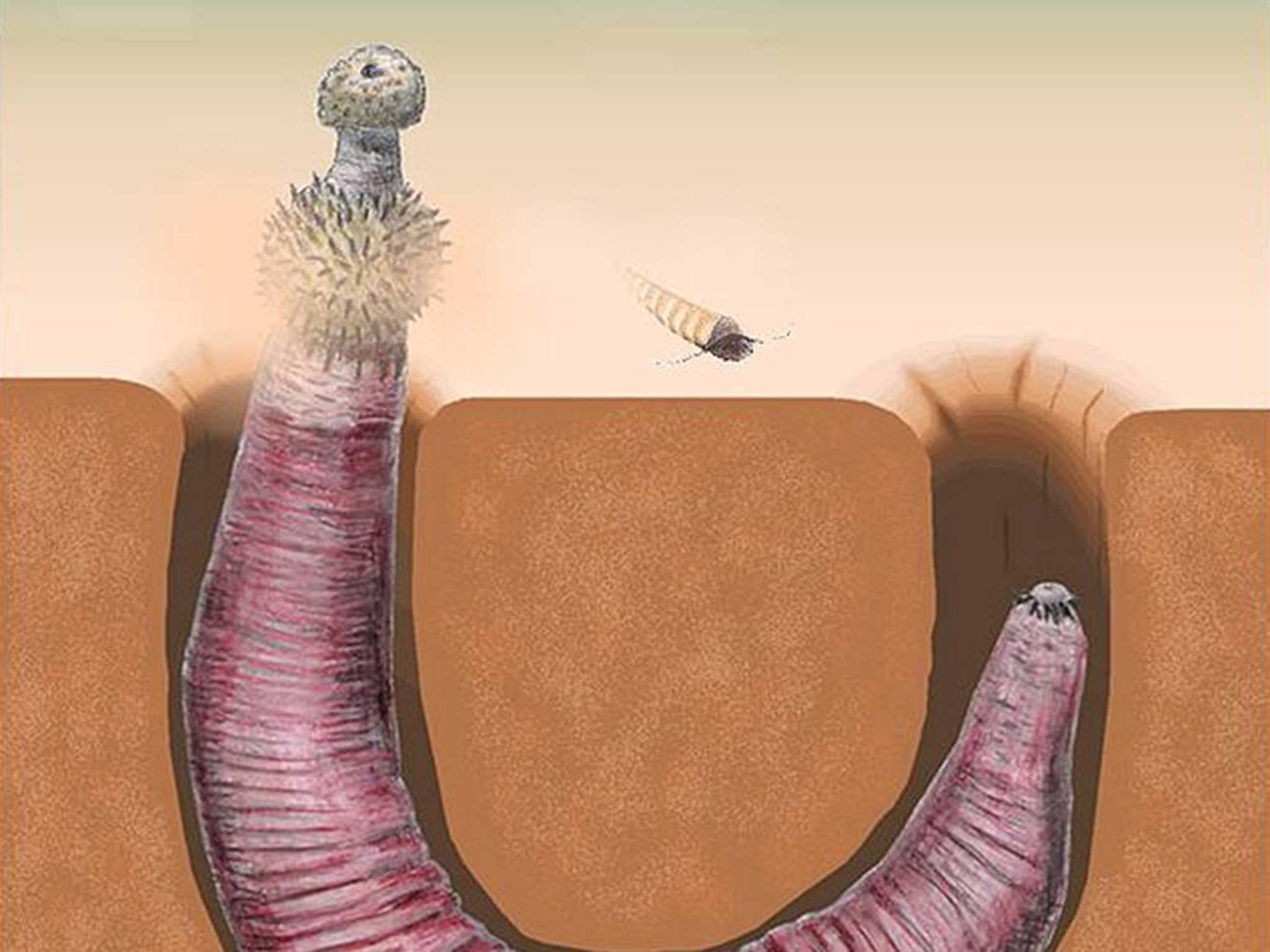

Ancient flesh-eating 'penis worm' dragged itself around by its teeth, scientists find

Researchers have created a 'dentists handbook' which they hope will help them identify other creatures from half a billion years ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have made an important breakthrough in the study of the unfortunately named ‘penis worm’ species that populated the earth half a billion years ago.

Using electron microscopy Cambridge researchers have been able to reconstruct the teeth of penis worms, also known as priapulids, in minute detail – allowing them to better identify other similar species across the world.

The creatures, which first emerged during the rapid evolutionary ‘Cambrian explosion’ period roughly half a billion years ago, were vicious predators able to turn their mouths inside-out and use their teeth to drag themselves forward.

Scientists have created a ‘dentists handbook’ by examining these ancient creatures’ teeth, each of which was shaped for a different purpose, and their research will allow them to build a fuller picture of the creatures who inhabited the planet millions of years ago.

During the Cambrian period, many creatures were soft-bodied so much of their remains have not been preserved except for their teeth.

“As teeth are the most hardy and resilient parts of animals, they are much more common as fossils than whole soft-bodied specimens,” Dr Martin Smith, a postdoctoral researcher in Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences and the paper’s lead author, explained.

“But when these teeth – which are only about a millimetre long – are found, they are easily misidentified as algal spores, rather than as parts of animals. Now that we understand the structure of these tiny fossils, we are much better placed to a wide suite of enigmatic fossils.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments