Pottery shards reveal ‘naughty pupils’ in ancient Egypt may have been forced to write lines as punishment

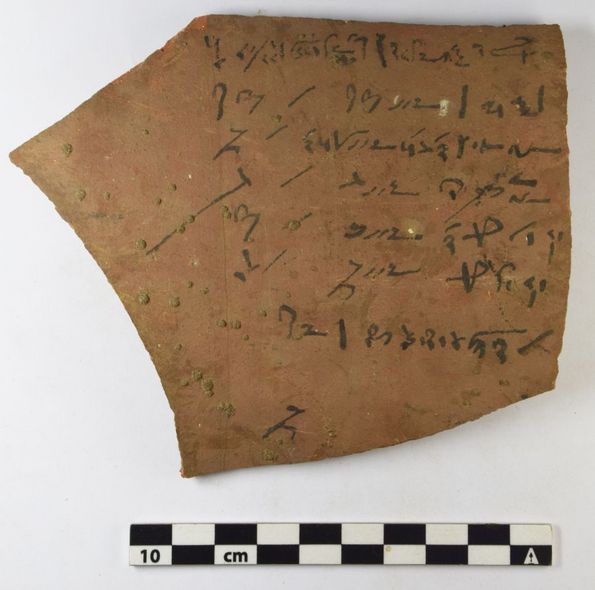

The fragments have notes inscribed with the same one or two characters each time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Naughty pupils” in ancient Egypt weren’t spared the wrath of their teachers and apparently wrote lines on pottery as school punishment, according to new findings.

Archaeologists recovered more than 18,000 pot shards from the long-lost city of Athribis in central Egypt that detailed daily life in the region about 2,000 years ago.

The shards – known as ostraca – were remains of vessels and jars which served as writing materials akin to “notepads”, said scientists, including those from the University of Tübingen in Germany.

The findings, described in the journal Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, revealed that the ostraca recovered from ancient Athribis documented lists of names, purchases of food and everyday objects, trade, teaching materials and writings from a school, including the punishment lines.

Egyptologists said it is very rare to find such a large volume of pottery shards, providing rich insights into the daily life of ancient Egyptians of this time period.

They said about 80 per cent of the pot shards were inscribed in demotic, the common administrative script in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods which developed from hieratic after 600 BC.

Researchers also came across pottery shards with Greek, hieroglyphic and, more rarely, Coptic and Arabic scripts, hinting at a multicultural history of the ancient city during this time.

There were also special pictorial ostraca recovered in the study that showed various figurative representations such as animals, including scorpions, swallows, humans, gods from the nearby temple and geometric figures.

The contents of the pot pieces, researchers said, varied from lists of different names to accounts of various foods and items of daily use.

A large number of ostraca, they said, could be from an ancient school.

“There are lists of months, numbers, arithmetic problems, grammar exercises and a ‘bird alphabet’ – each letter was assigned a bird whose name began with that letter,” Christian Leitz, of the Institute for Ancient Near Eastern Studies (IANES) at the University of Tübingen, said in a statement.

A large quantity of the pot shards, in “three-digit numbers”, contained writing exercises that researchers speculate may have been punishment given to “naughty pupils” in the ancient Egyptian school.

These ostraca, they said, were inscribed with the same one or two characters each time, both on the front and back.

Researchers also recovered shards containing writing exercises, including one where a pupil seemingly wrote numbers from one to 100, which they said the student managed to do, but got confused and wrote 86 instead of 84 in the sequence between 83 and 85.

“First part of the exercise consisted of writing the numbers, probably from 1 to 100, which the student managed to do, except for a confusion of 86 to 84 on row l. x+8 of the first column,” they wrote in the study.

Such large quantities of ostraca, inscribed with ink and a reed or hollow stick (calamus), have only been made once before, in the workers’ settlement of Deir el-Medineh, near the Valley of the Kings in Luxor in Egypt, researchers pointed out.

While these ancient texts were mostly notes about medical practices and medicine, the new discovery in Athribis reveals fresh insights into the daily life of common people in the ancient civilisation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments