Common virus could be behind Alzheimer’s in some people, scientists say

Herpes virus may linger in gut and travel to brain via vagus nerve to cause a type of Alzheimer’s

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A chronic gut infection caused by a common virus may be linked to the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, a new study has found.

Cytomegalovirus, or HCMV, is one of nine herpes viruses that most people are exposed to in the first few decades of life. Unlike most herpes viruses, however, it is not considered to be sexually transmitted.

Researchers at Arizona University in the US found the virus may linger in the gut and travel to the brain via the vagus nerve that connects the two.

Once there, it may trigger immune system changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease, according to the study, published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“We think we found a biologically unique subtype of Alzheimer’s that may affect 25-45 per cent of people with this disease,” the study’s co-author, Ben Readhead, said.

If the findings are validated by further research, existing antiviral drugs could be tested to treat or prevent this form of Alzheimer’s disease. This can be supported by a blood test currently in development to identify patients with an active HCMV infection.

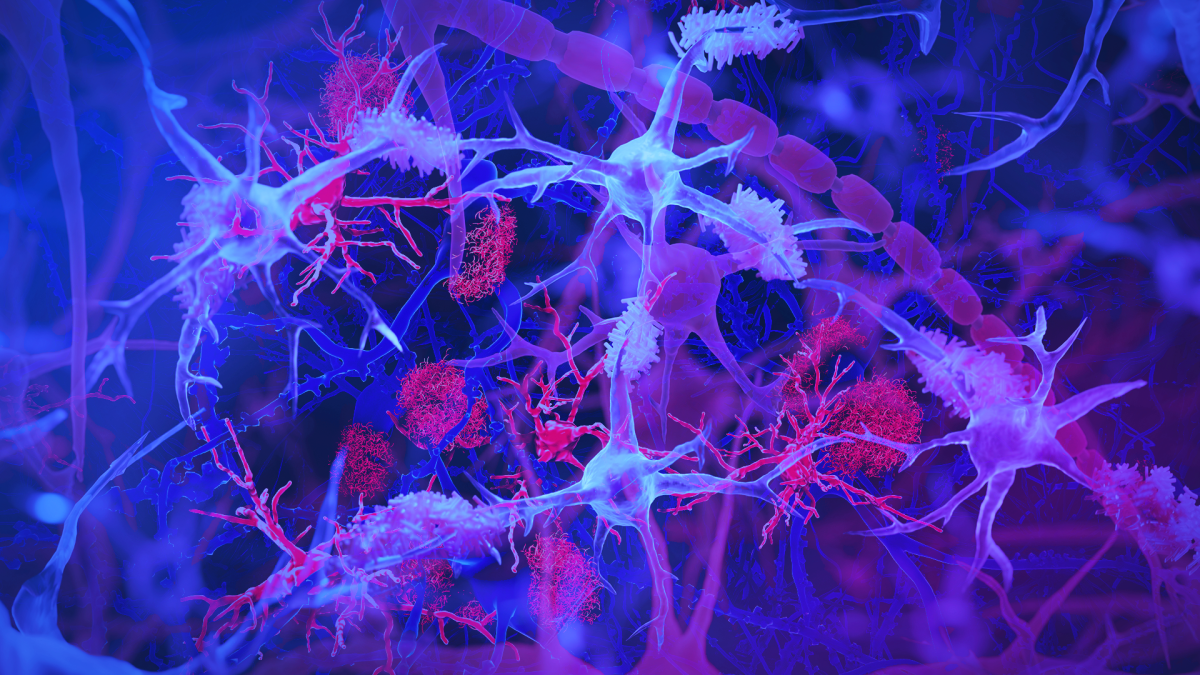

“This subtype of Alzheimer’s includes the hallmark amyloid plaques and tau tangles — microscopic brain abnormalities used for diagnosis – and features a distinct biological profile of virus, antibodies and immune cells in the brain,” Dr Readhead said.

In some people who develop a chronic intestinal infection from HCMV, the virus may travel to the brain via the bloodstream or through the vagus nerve.

Once in the brain, the virus prompts immune cells called microglia to turn on their expression of a gene called CD83 which has been linked in a previous study to Alzheimer’s.

While microglia are initially protective against infections, a sustained increase in their activity may lead to chronic inflammation and neuronal damage – implicated in the progression of diseases like Alzheimer’s.

An earlier study, published last year in the journal Nature, found the postmortem brains of research participants with Alzheimer’s disease were more likely than those without the neurological condition to harbour CD83 microglia.

It also found an antibody in their intestines suggesting that an infection likely contributed to this form of Alzheimer’s.

In the latest study, scientists examined spinal fluid from the same individuals and found these antibodies were specifically against cytomegalovirus. They also found HCMV in the vagus nerve, indicating this is the route the virus takes to enter the brain.

Researchers used lab-grown brain cell models to show the virus can induce changes related to Alzheimer’s such as the production of amyloid and tau proteins linked to the death of nerve cells.

Further independent studies are needed to put the new findings to the test, however, researchers said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments