A step forward for science – a step back for Britain's science sector

Cambridge team reveals potential breakthrough for brain-damaged patients – but lack of funding means they're moving to Canada

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A leading neuroscientist who is about to leave Britain for a research post overseas revealed yesterday that he is on the brink of a breakthrough in communicating with people who inhabit the twilight zone between consciousness and unconsciousness, known as being in a vegetative state.

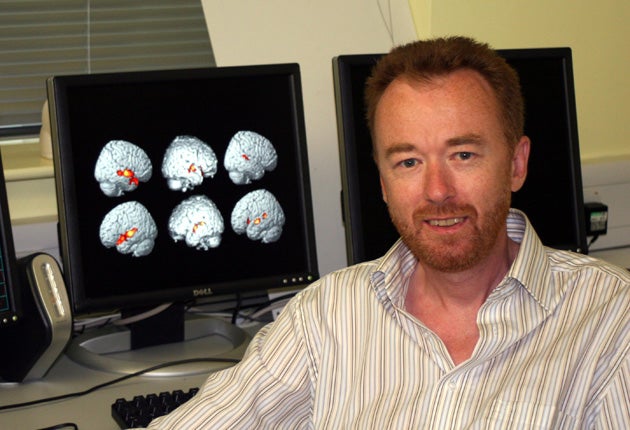

Dr Adrian Owen, of the Medical Research Council's Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit in Cambridge, said it was "inevitable" that "in the very near future" a means would be found of enabling people in a vegetative state to answer questions about their condition and express their needs.

But Britain is unlikely to enjoy the kudos of the advance, because the scientists at the forefront of the research are moving to Canada to join a multi-million dollar programme.

Dr Owen and between four and seven members of his team are taking up research posts at the University of Western Ontario under a 20m Canadian dollar (£13m) scheme, half funded by the Canadian government and half by the university.

Senior British scientists have highlighted the move in the context of warnings about an imminent "brain drain" as the Coalition Government prepares to make heavy cuts in science research spending.

But Dr Owen said Ontario had approached him more than a year ago, long before discussion of research funding cuts in the UK, and that it had been a case of "pull, not push". "Scientists move around all the time. I want to try and push things a bit further [in Canada]," he said.

Dr Owen and his team stunned the world earlier this year when they revealed they could read the minds of people in a vegetative state who had been thought to lack all awareness, using an advanced brain-scanner.

One patient, a 29-year-old man presumed to have been in a vegetative state for five years following a car accident, was able to communicate by thought alone, giving simple "yes" and "no" answers to questions. He had emerged from a coma after the accident, his eyes were open and he followed the normal sleep-wake cycle, but had shown no awareness of the environment around him and did not react to any visual, auditory or tactile stimuli.

Yet when researchers put him in the scanner using a technique known as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and instructed him to imagine playing a game of tennis for "yes" and walking through his home for "no", they found he was able to answer a set of six test questions correctly.

The drawback of the method, published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), was that it took time to analyse his responses, so it was not possible to have a conversation in real time. Dr Owen said there was now an urgent need to develop cheaper, more portable means of making contact with such patients to find out what they were feeling and what their needs were.

Several thousand people are in a vegetative state in hospitals at any one time in Britain – cut off from contact with their family and carers. Dr Owen said he could not disclose details of his latest research in advance of its publication in a scientific journal, but it involved the use of EEG recordings of brain activity which, when analysed, could be used as a means of communication. "We are going to get to the position where someone [in a vegetative state] can communicate on a regular basis. It will likely involve a set of electrodes which they will wear on their head – an electrode cap – connected to a computer somewhere. It means we can bring it to the bedside and it will be relatively affordable: £20,000 to £30,000," he said.

Some scientists have criticised the research, on the grounds that a machine can be programmed to respond yes or no to questions, and the presence of the skill cannot be equated with the presence of consciousness. "We cannot be certain whether we are interacting with a sentient, much less a competent, person," the NEJM said in an editorial.

But Dr Owen dismissed the criticism, arguing that on such a basis it was possible to question the consciousness of anybody. "We are using brain imaging as a form of action. We ask the patients to activate their brain [by imagining a game of tennis] and when it is repeated over and over, it is convincing evidence that they are conscious," he said.

"We now have a moral responsibility to find ways of allowing them to express themselves. It is technically challenging – you can't put them in the fMRI scanner every time you want to find out if they are feeling pain. I think it is inevitable we will be able to use an EEG-based system before long. The fMRI will continue to be the main method for assessing patients but other technologies will be brought in."

Not all patients in a vegetative state were able to communicate their thoughts – only four out of 23 showed signs of responding in the New England Journal study. But for that minority there was now a prospect that they might one day play a role in decisions about their own welfare.

"I am quite sure that using the same sorts of imagery tasks, the technique will work with EEG recordings and it will work with 100 per cent reliability," Dr Owen said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments