Review: Shemekia Copeland's take on 2020 turmoil falls short

Shemekia Copeland has loads of talent, writes Scott Stroud of The Associated Press, and she's the latest to try to explain 2020 through songs of protest and social commentary

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

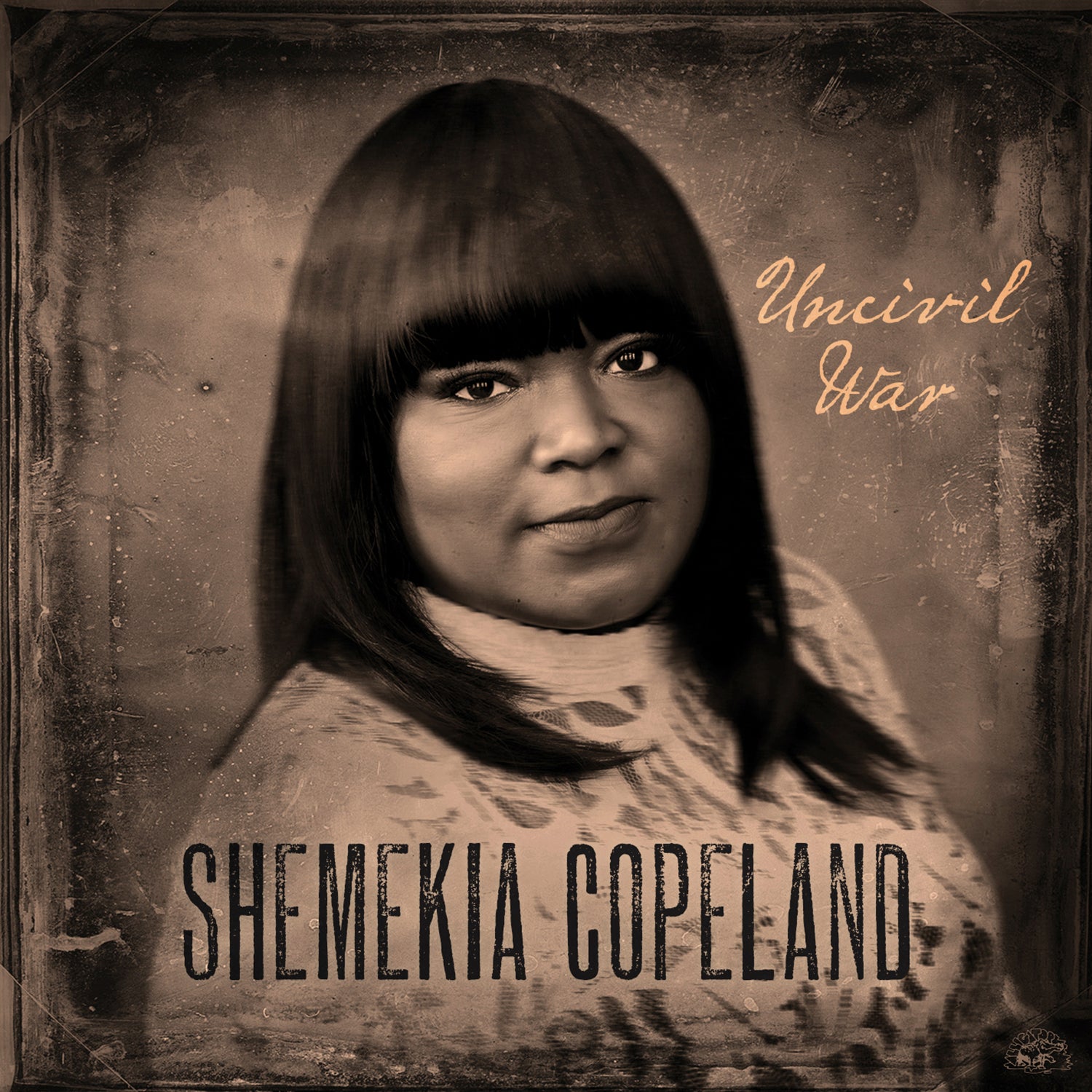

Your support makes all the difference.Shemekia Copeland, “Uncivil War" (Alligator)

The best protest songs come from a deep well of outrage connecting with a visceral sense of injustice or posing an urgent question. Think “What if you knew her and found her dead on the ground?"

A lot of artists are trying these days to make sense of a world in turmoil. Among them is Shemekia Copeland, whose new album, “Uncivil War," offers commentary on everything from the proliferation of guns to civil rights marches to the more universal challenge of simply getting along.

“I'm trying to put the ‘united' back in the United States," Copeland explains.

A worthy goal, to be sure, and Copeland seems suited to the task. The daughter of Texas bluesman Johnny Copeland, she's made her mark in her own right with a big voice and a straight-ahead delivery.

Ultimately, though, “Uncivil War" falls short. Much of it feels contrived and self-conscious, as if she and producer Will Kimbrough, who co-wrote many of the songs, set out to write protest music but forgot the visceral outrage. The songs lean too much on the obvious to make the necessary connections.

The title cut is a good example. It has some nice touches, including the elegant guitar accents of dobro legend Jerry Douglas and a swelling chorus that will play well live if live music ever comes back. But the sentiment leans too much on tired lines like “The lines are drawn, the gloves are off” to really soar.

Copeland has earned respect in the roots-rock world with less self-conscious, more muscular blues. She comes closest to her own standard here on “Clotilda’s On Fire," about the last slave ship to arrive in America, and “Walk Until I Ride," a more authentic-feeling tribute to the civil rights movement that echoes the Staple Singers.

The rest seems unlikely to find its way into the canon of era-defining music.