‘I’m a refugee whose life was transformed by compassion - where is our humanity now?’

The war in Gaza has brought back a flood of memories for A&E consultant Dr Waheed Arian, who as a 12-year-old child had to flee rocket attacks on the streets of Kabul. Here, he tells Peter Stanford how his refugee journey took him across the mountains to Pakistan then to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and how he’s dedicated his life to helping innocent victims caught up in today’s conflicts

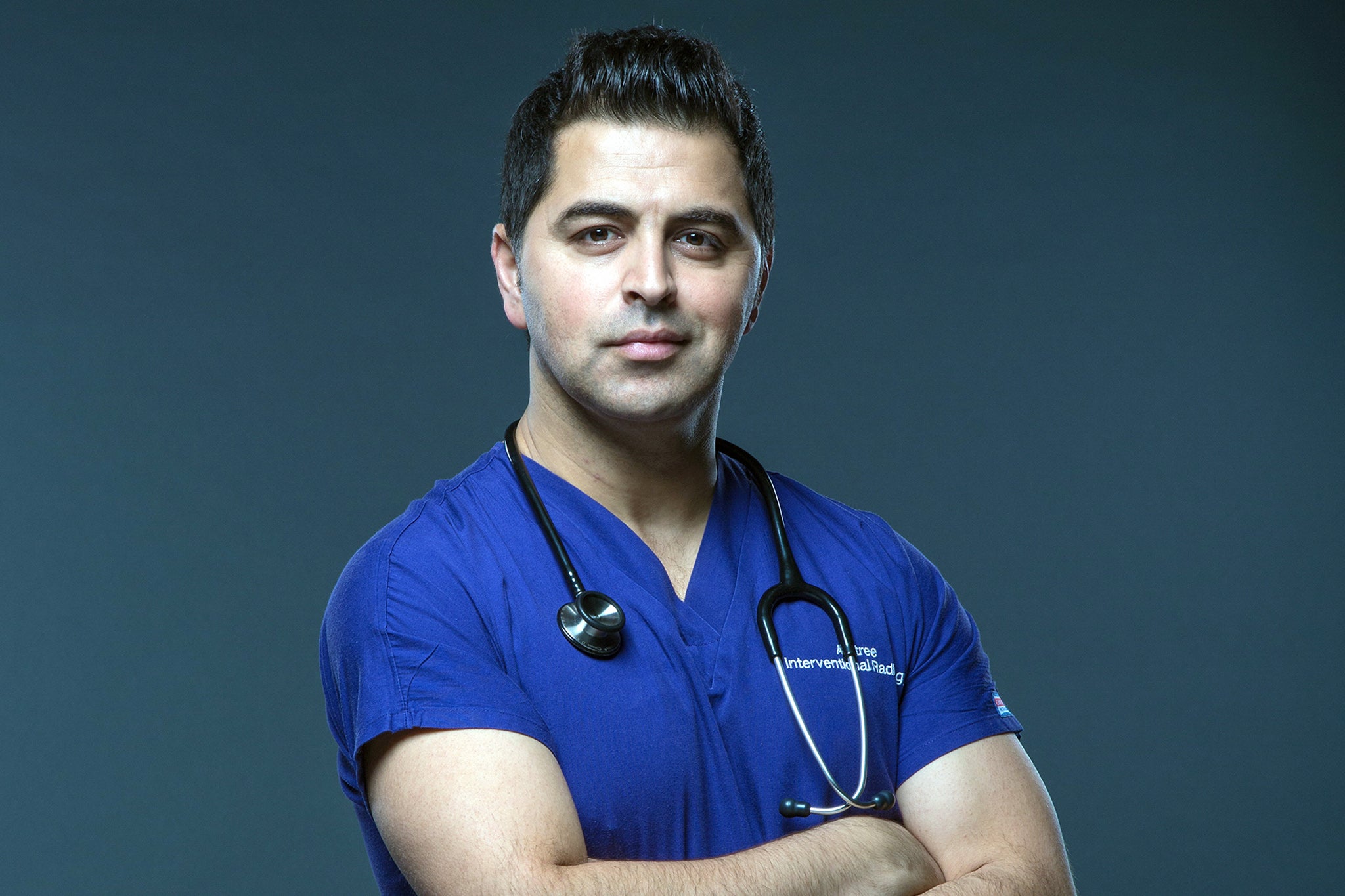

The horror of the pictures coming from Israel and Gaza has had a profound impact on everyone this past month. For Shrewsbury-based A&E consultant Dr Waheed Arian, though, it is quite particular. They take him back to his childhood in war-torn Afghanistan in the 1980s and 1990s.

“I was recently scrolling,” the 40-year-old doctor says, “and I saw this image from a healthcare worker in Gaza with two things in his hand. When I looked closer, they were the lower legs of a child. One had a shoe on it and the other didn’t.” In that moment he experienced what he calls “a process of retraumatisation”. He says this calmly, as if stepping back and diagnosing himself.

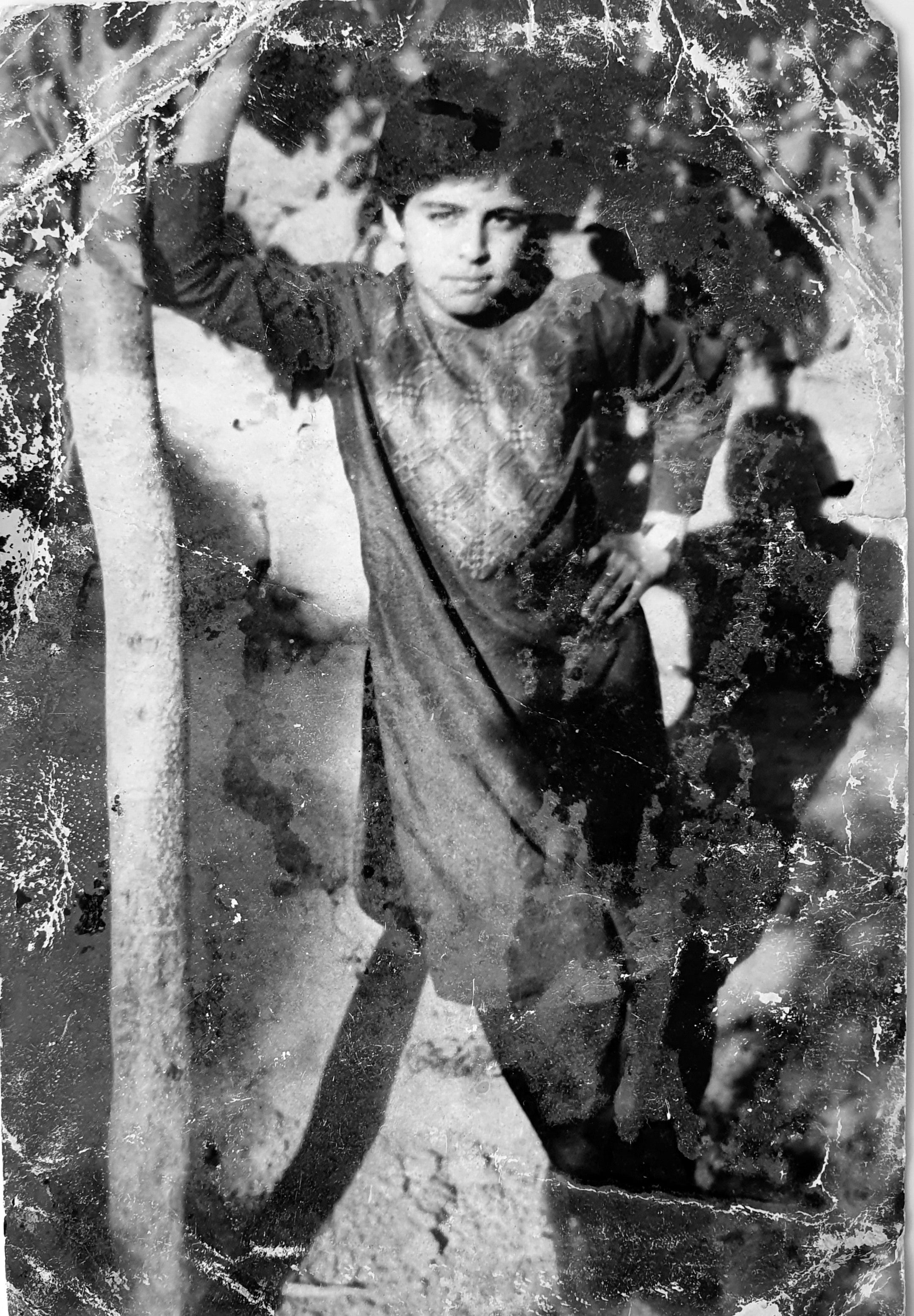

The first 15 years of Arian’s life were spent in a perpetual state of war, as first Mujahideen fighters drove Soviet occupiers out of Afghanistan, and then with the rise of the Taliban. He was just five in 1988 when he first fled with his family from Kabul over mountain paths to a refugee camp in Pakistan. Seven years later they returned to their home, hoping the situation had improved, but it remained a battlefield.

“I am not comparing Kabul to Gaza,” he says, “because trauma shouldn’t be compared.” And yet, seeing the images is enough to transport him back to being a 12-year-old when rockets fell everywhere around him.

His young eyes registered and stored everything. The details, he says, remain a part of him. “Families were moving for safety but, on the way, people were getting caught by the rockets. I remember seeing arms lying around, somebody’s head over there, somebody’s body, but we had to keep moving.”

“The memory, your body, everything is digesting all that information, taking it in. The trauma of living through a war never goes away,” he explains.

Watching it happen to other children in another place acts as a trigger. “Human beings suffering, parents losing their children. And now I have two children of my own [aged seven and four] So, when I saw that image, I went and cried. Later, I went home and kissed my children’s feet.”

Tears are filling his eyes as he speaks, but he sits upright and unflinching opposite me in the cafe in central London. He has learnt about dealing with trauma; don’t push it away, or try to bury it, because it will come back when you are least expecting it. It happened, he recalls, when he was completing his medical training in 2008 at Imperial College in London after studying at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, tipping him into a breakdown. “My coping mechanism was fight or flight, but I had run out of adrenalin.”

And again, two years later, just at the point when he met his English wife, Davina. “The memories come when you don’t want them. You feel ashamed. You feel neglected. You feel hopeless. Until I met her, I didn’t talk about these things.”

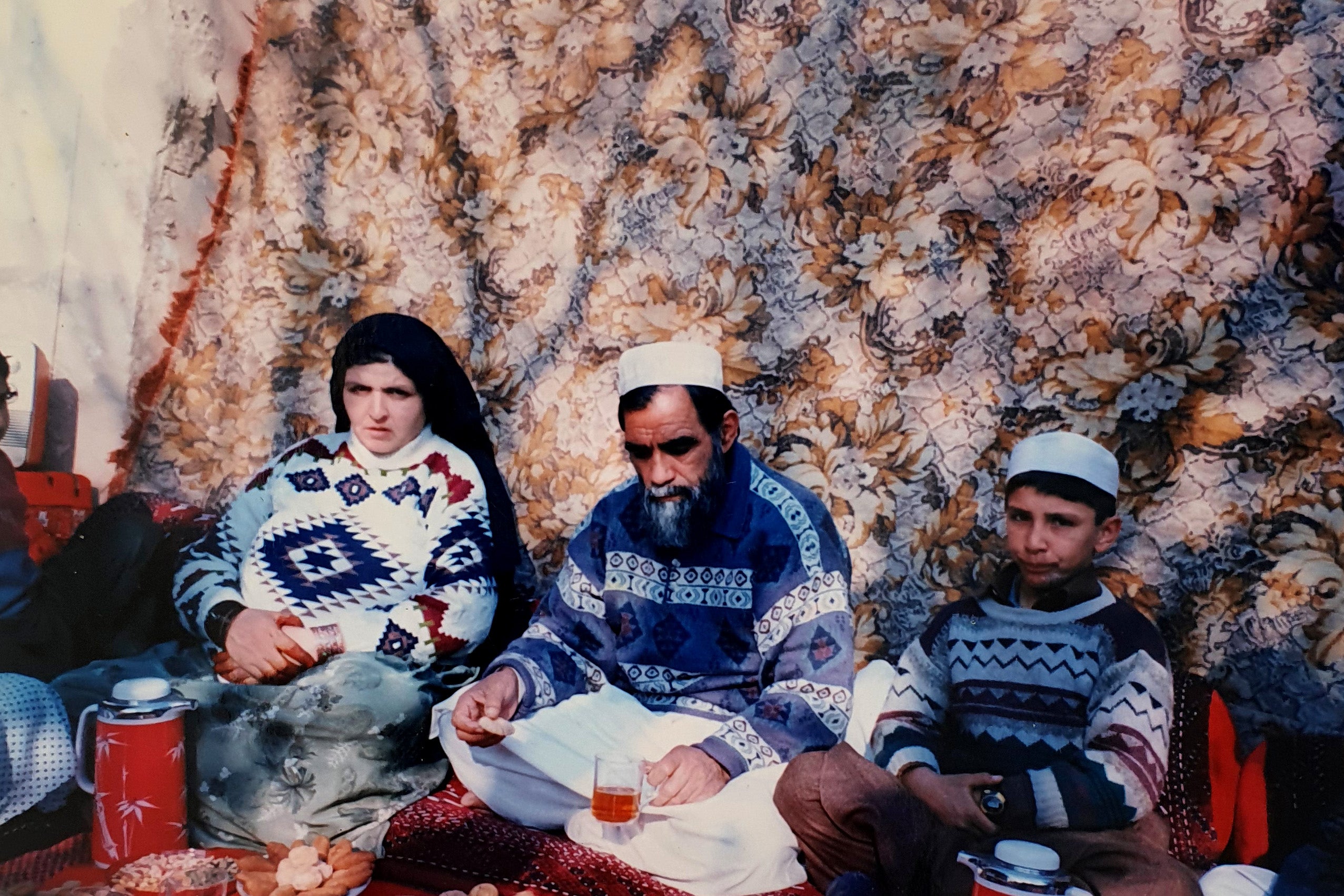

Arian was the fifth of 11 children. In the late 1980s, his father (a cashier with no formal education) decided the family had to escape, making the long trek into neighbouring Pakistan. They travelled by night for seven days on horses and donkeys over the same routes that the Mujahideen used to bring in weapons, provided by the West, to fight against the Soviet invaders.

Russian spotter planes were patrolling and if they glimpsed movement on the ground, they would launch an attack. Waheed and his father were ahead on the trail and were spotted. “There was a time lapse between that and the fighter jets arriving, so we ran into a little village that had been deserted and found a house.”

In traditional Afghan buildings, he says, there is one room used for baking and the oven is dug into the floor. “He took me down into the oven, covered me with his body and said that if anything happened to him that I [as the oldest boy] would be responsible for the family.” The jets destroyed the house but, in their below-floor-level shelter, father and son survived.

“That,” he says, “was the loss of childhood, when I started thinking when is he going to die? And if it happens, what do I do?” Arriving at the refugee camp over the Pakistani border in Peshawar, the whole family was given first just one tent, and then “a one-room mud house”. Malaria was rife and Waheed had a cough that wouldn’t go away. The camp doctor sent him to see a lung specialist in the city centre.

“Outside it was hot and sticky, but the consultant had air conditioning. I was taking it all in – the clean room, the white coat, the smile on his face, the kind words.” He was sent next door for an X-ray. “I was so proud of the picture that I didn’t worry what it showed. There, my fascination began with medicine.”

He had tuberculosis and wasn’t given the all-clear until a year later by the same doctor who gave him a stethoscope and some of his textbooks. “Son, one day you’ll be a doctor,” he told me. “Even in our darkest hours, we find kindness. As refugees, we were in our weakest, darkest place, and I held on to that kindness, as other refugees will.”

Once back in Kabul in the chaos of the civil war, the family made a momentous decision that would change his life. They sold their house to raise thousands of dollars to get their oldest son, then 16, into the UK on what they said was a refugee visa so he could get an education. He was sent on an aeroplane with very little money and knew only one person at the other end – an old family friend called Hakim who was working as a taxi driver in London. Aided by smugglers, he and the two other young men he travelled with were told to destroy their Afghan passports before the plane landed. They tried to burn them in the toilet but set off the fire alarm. All were arrested and on landing he was sent to HMP Feltham.

After weeks in custody, a judge dismissed the charges against him and granted him full refugee status. Hakim met him from the court and took him to the London flat he shared with other refugees. For the two-and-a-half years that followed while his asylum claim was being processed, he had three jobs by day – cleaner, kitchen porter and sales – and studied at night, first to get his English up to speed and then at night school where he got six AS levels and then three A levels (psychology, biology and chemistry), all at A grade.

Having met someone he worked with in sales at British Gas, a young Pakistani who had just graduated from Cambridge, he was encouraged to apply for a place too and succeeded. With his grades and determined attitude, he was offered a place and bursary at Trinity Hall.

A happy ending? Not really. The trauma of all he had been through would regularly rise up in him. “When I was looking at red buses in London, they would turn into tanks. It was a flashback. In the middle of the night, I’d remember the rockets and jump up. That is a PTSD symptom.”

His Cambridge years were tough too. In his studies, his English, while fluent, was not quite up to the standard of others and he struggled academically. “I didn’t fit into that world. There was my trauma and then there was the social aspect as well. It wasn’t the other students’ fault. I had a completely different childhood from them.”

After qualifying as a doctor in 2006, he spent a year at Harvard Medical School in 2008 before returning to work as a radiologist then in A&E, first in London, then Liverpool. In 2008, he made the first of many visits home to reunite with his family in Afghanistan – helping to establish medical and humanitarian projects there.

In 2014, he founded Arian Teleheal, a phone referral system that enables doctors working with refugees in war zones such as Southern Sudan, Uganda and Yemen to have instant phone access to specialists in developed countries to give expert guidance on treatment.

His agency had an 88 per cent success rate in playing its part in saving those rushed into poorly resourced hospitals. It has also seen him go on to work with the United Nations and the World Health Organisation, which wanted to draw on both his professional and personal knowledge of global hotspots. Today, he is actively promoting peace and advocating for displaced people across the Middle East.

Awards, medals and documentaries have followed his work but Arian’s real purpose is to get people to see refugees in a different light; to recognise our common humanity. Today, as the situation worsens, he is actively advocating for displaced people across the Middle East.

“I agree that not everyone who says they are a refugee is a refugee, but there has to be a fair system in place to review each case and understand their stories. My story is just one of many. I have proved what I could do with my potential, but there are so many others like me.”

Dehumanising refugees is, he believes passionately, “something very dangerous”. Today, Arian is in contact with many refugees who were welcomed after the fall of Kabul but are now still housed in hotels. “They are crammed four or five to a room, unable to make their own food, for a year and a half. They came with traumatic experiences, but what has happened here is retraumatising.”

All trauma, Arian says, should be treated just as we would treat a physical injury. “As an A&E doctor working in the NHS, I see people coming in with all sorts of traumas again and again, with suicidal thoughts or self-harm, drug and alcohol addictions. We patch them up and send them back into the community but the problem remains.”

That ongoing failure to tackle the long-lasting effects of trauma – whether that is for refugees or otherwise – lies behind his new venture, Arian Wellbeing. In partnership with local authorities and the NHS, online and in person, using a mixture of clinical psychologists, registered therapists and personal trainers, it seeks to help those with blighted lives to find ways to move forward.

In his own life, getting fit and exercising regularly helps him process trauma, and he has developed his own professional barrier – as a doctor and humanitarian that helps to stop going right back into it, but “it is not easy”.

Arian’s mother died of cancer in 2020 but his father Taj Mohammad still lives in Kabul with one of his brothers and his sisters, all under the strictures of the Taliban regime. Going home, he says, is bittersweet, and traumatic memories are always close to the surface. The situation there is terrible, he reports, because of the lack of food and jobs. “The world has given up on Afghanistan. You can give up on political engagement. But you can’t give up on 40 million people.”

He remains, though, he insists, a determined optimist. “My life has been transformed by compassion. We need to treat all people with humanity regardless of the colour of their skin or background.” Society needs reminding of what is to be gained by such an approach, and he remains happy to continue telling his story, albeit at a cost.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments