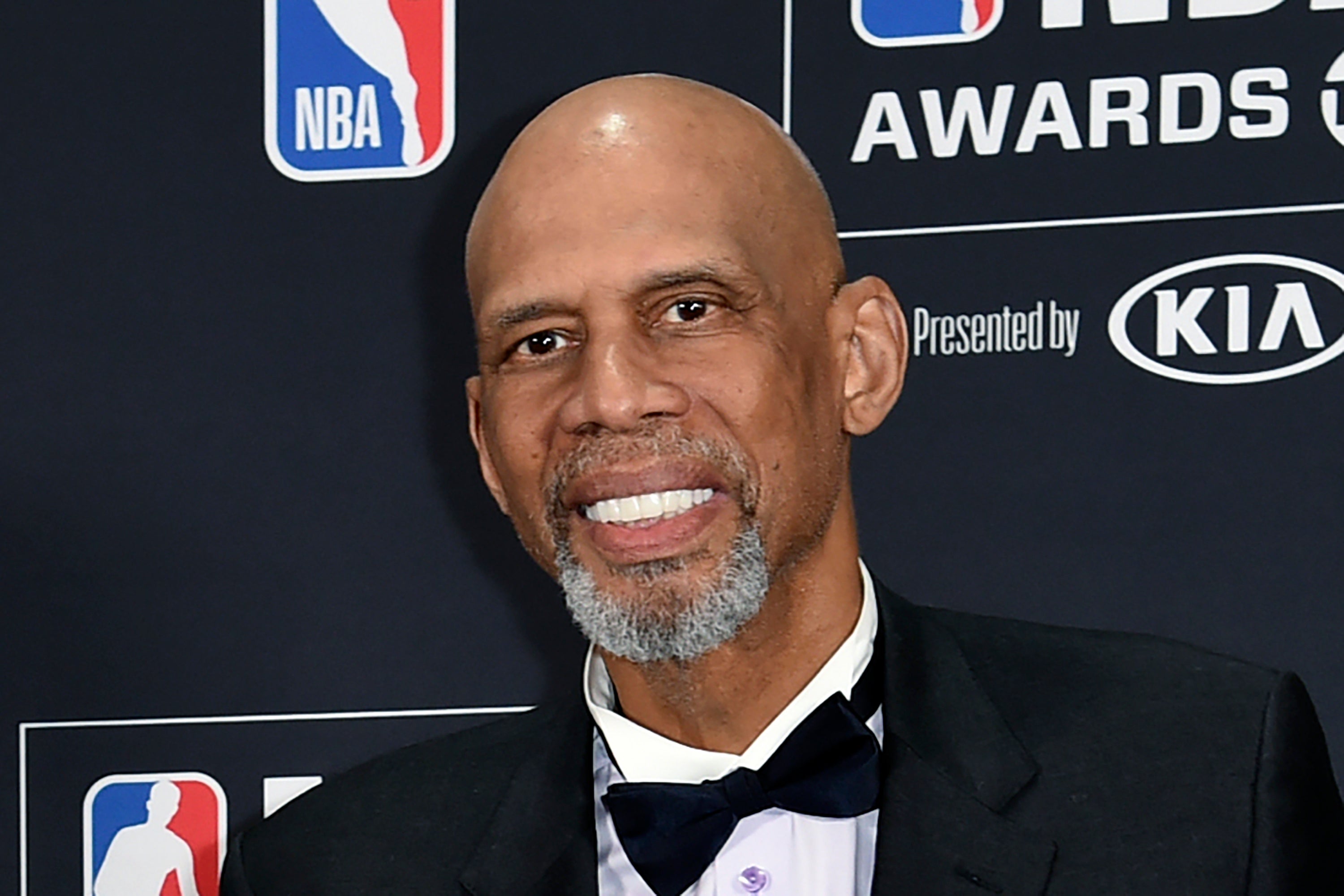

Q&A: Abdul-Jabbar talks new documentary, MLK, social justice

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is an NBA legend, but the man known for his trademark skyhook shot has also devoted his life advocating for equality and social justice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is an NBA legend, but the man known for his trademark skyhook shot has also devoted his life advocating for equality and social justice.

Abdul-Jabbar will take another step in his activism walk as an executive producer and narrator of the documentary “Fight the Power: The Movements That Changed America ” which premieres Saturday on the History Channel. The one-hour documentary explores the history of protests that shaped the course for justice in America.

“Fight the Power” examines the labor movement of the 1880s, women’s suffrage and civil rights along with the LGBTQ+ and Black Lives Matter initiatives. It also features footage from Abdul-Jabbar’s personal experiences when he covered one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s news conferences at age 17 and attended the famous 1967 Cleveland Summit, where prominent Black athletes such as Bill Russell and Jim Brown discussed Muhammad Ali’s refusal to serve in the Vietnam War.

Abdul-Jabbar said co-executive producer Deborah Morales was adamant about the documentary needing to include all groups impacted by “bigotry and discrimination.” His pursuit toward social justice for marginalized people prompted the NBA to create an award bearing his name last month.

In a recent interview, Abdul-Jabbar spoke with The Associated Press about the importance of project, his unforgettable conversation with King, and how Emmett Till and James Baldwin were catalysts to his social justice journey.

Remarks have been edited for clarity and brevity.

AP: Why does the documentary focus on several different movements?

ABDUL-JABBAR: For me, it is trying to show that what Black Americans must deal with has been experienced by other marginalized groups. All of us at one time or another have been targeted by the dominant group. So, we must understand that all of us are in the same boat and we have to stick up for the rights of every marginalized group, not just the ones that we’re in that causes controversy, but to look at other issues.”

AP: When did you first realize people of color were treated unfairly in this country?

ABDUL-JABBAR: It started when I was 8 years old. That’s how old I was when Emmett Till was murdered. And I didn’t understand it. I asked my parents to explain it. They didn’t have the words. I was like “Where do I live? Why am I a target here?

AP: How did you find some clarity?

ABDUL-JABBAR: I was in the eighth grade. I was about 13 years old, and I read James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time.” That explained it all to me. It gave me an idea of what I had to do and what Black Americans had to do in order to get out from underneath all of this oppression.

AP: You are a champion on the basketball court and voice of inclusivity. Did you envision this path for yourself, even after your Hall of Fame hoops career?

ABDUL-JABBAR: I never really saw myself as a leader in all of it. I was someone who spoke out. I had enough nerve (and was) crazy enough to speak out about things. If we don’t talk about the issues, they don’t get dealt with. So, somebody has to go out there and speak. You remember all the controversy behind LeBron (James) saying, “Shut up and dribble is a lot of B.S.” You have to just get to that point where you can say that and have people understand what it means.

AP: Which personal experience highlighted in the doc stands out to you the most?

ABDUL-JABBAR: When I was 17 and I got to interview Dr. King. That was incredible. Just to exchange some words with him. But to understand what his message actually meant, I never really compared it side by side with what Malcolm X was talking about. When you do that, you find out actually that they had the two different approaches to the same end: freedom, justice and equality for all Americans. Equality, that’s what it should be about.

AP: What’s your biggest takeaway from the documentary?

ABDUL-JABBAR: It’s a series of steps forward, but there’s also some backsliding and a lot of attempts to move everything backwards. We had to deal with what people were really talking about, making America great again. It wasn’t about being great. It was about being ruled by a certain group of people. They thought that was great. But our country should be ruled by the American people. And all of us have a vote in. All of us have a voice. And we have to use our voices and our votes in a righteous way.

AP: Are there other topics you would like to explore in the future?

ABDUL-JABBAR: I’m hoping I can do a more documentary style piece on the Underground Railroad. There’s a dramatic piece on right now that’s very well done. But we should get into the details and let America understand what it was all about, because it's an interesting story.

AP: What would be your angle?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Some of the people involved that you would never, ever be considered to be heroes of the Underground Railroad. For example, what do you know about Wild Bill Hickok? When he was a teenager, he and his father and uncle help escaping slaves get to Canada. He lived in central Illinois and the escaping slaves would go from the Mississippi River up to Chicago and southern Wisconsin, get on a boat, go across Lake Michigan. When they got to Canada, they were free. There’s a whole lot of stories like that.