Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

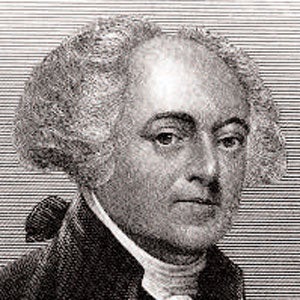

A brilliant but short-tempered lawyer and small-time farmer from Massachussets, Adams first made a name for himself by defending the British soldiers accused of killing unarmed civilians in the Boston Massacre in 1770. Soon afterwards, he became involved in the struggle for independence. An influential pamphleteer, he served as a diplomat in France and the Netherlands during the Revolutionary War, and was on the panel charged with drafting the Declaration of Independence. In 1789 he was elected vice-president under George Washington – a post that he found frustrating: "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived," he complained to his wife. His concern for the minutiae of protocol was much mocked at this stage in his career; his enemies referred to him derisively as "His Rotundity".

He became president at a time when the Napoleonic wars were causing great difficulties for the US, both at sea and in the intense partisanship that the issue provoked at home. The factional divisions that had begun to appear under Washington soon dominated his presidency.

Adams was not helped by the then unresolved constitutional anomaly whereby the runner-up in the presidential election automatically became vice-president. Adams was a Federalist; Thomas Jefferson, his Vice-President, was a Republican; and the election contest between the former friends had been a bitter one. There were predictable tensions.

Adams's presidency was also coloured by a deteriorating relationship with France – which, under the ruling Directory, suspended commercial relations and refused to receive US envoys. This culminated in 1797 with the scandal known as the "X, Y, Z Affair", in which bribes were demanded by French agents in return for the possible normalisation of diplomatic relations. Adams exposed this in Congress, and the resulting anti-French feeling increased his popularity, at the expense of the Republicans. This encouraged him to pass the notorious Alien and Sedition Acts (1798), which were ostensibly intended to frighten foreign agents out of the country but also dealt a severe blow to freedom of the press by making it a crime to "write, print, utter or publish... scandalous and malicious writing or writing against the government of the United States..." (This aspect of the legislation was allowed to lapse in 1800.)

Adams built up the navy to defend US shipping against French privateers, but resisted popular pressure for war, and sending a peace mission to France probably contributed to his defeat in the 1800 election. (Nonetheless, he considered his diplomacy "the most splendid diamond in my crown".) He spent the final hours of his administration appointing his supporters to many judgeships and court offices. He then ungraciously left town to avoid Jefferson's inauguration. Jefferson undid many of these "Midnight Appointments".

Adams retired to his farm at Quincy, Massachussetts, where he lived not only to be 90 but also to see his son, John Quincy Adams, elected president. (His other two sons were profligate: one died an alcoholic at 30; the other lived rather longer but also drank, and died in debt.) In later years Adams was reconciled to Thomas Jefferson, and the two enjoyed a famous correspondence. Bizarrely, they died on the same day: 4 July 1826, which also happened to be the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

In his own words

"People and nations are forged in the fires of adversity."

"The people, when they have been unchecked, have been as unjust, tyrannical, brutal, barbarous, and cruel, as any king... The majority has eternally... usurped over the rights of the minority."

"By my physical constitution, I am but an ordinary man. The times alone have destined me to fame – and even these have not been able to give me much."

In others' words

"Vain, irritable, and a bad calculator of the force and probable effect of the motives which govern men." Thomas Jefferson

"He... is always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes, and in some things, absolutely out of his senses." Benjamin Franklin

"You stand nearly alone in the history of our public men in never having had your integrity called into question or even suspected." Benjamin Rush

Minutiae

On his farm in Quincy, he began each day by drinking half a pint of cider.

He was the first president whose son became president too.

He was the first to live in the White House (then the Executive Mansion).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments