Was Nick Clegg's great aunt a Soviet agent?

The colourful love life and suspected treachery of a Russian countess exiled in London after the Bolshevik revolution kept the security services occupied for years. But what was the truth about Moura Budberg?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first time a British intelligence officer inquired about a mysterious Russian named Countess Moura Budberg, he was chasing gossip. It was well known to the spooks that a famous agent, Robert Bruce Lockhart, had fallen hopelessly in love with a woman named Moura when he was in Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution. Someone in the secret service was curious to know whether the woman under investigation in Estonia in 1921 as an alleged Soviet agent was the same person as Bruce Lockhart’s old flame. She was.

By the end of the 1920s, they had a more serious reason to gather information on the wild Countess. Having been cleared of suspicion in Estonia, and now living sometimes in Germany, sometimes in Italy, she wanted to enter Britain to be with her niece, Baroness Kira von Engelhardt.

Baroness Engelhardt’s blameless life never troubled the British authorities, though she was forever at risk of being tainted by association with her aunt. During a spy scare in 1950, one MI5 officer sent a memo to another suggesting they look into “Kera [sic] Clegg, who appears to be an intimate friend of Moura Budberg”. He obviously did not know that this was her niece, as Engelhardt had changed her surname on marrying the editor of the British Medical Journal, Hugh Clegg.

The couple, and their Soviet connection, are now of particular interest as they were the grandparents of Nick Clegg. And while some intriguing details of the Deputy Prime Minister’s Russian relative have come to light since he first entered office, the extraordinary story of Moura’s life can finally be told following The Independent’s trawl through the National Archives.

Mr Clegg has described her as “a pretty imposing figure, utterly terrifying for a small boy”, who would “look at me sternly and say in a thick Russian accent, ‘Speak up, boy, you mumble’.” The British secret service’s various informants judged her to be “attractive but not good-looking and not really clever”, or “of great beauty and of no great morality”, or “an extremely intelligent and fascinating woman”, or “a very dangerous woman”, or an “absolute devil”, or the innocent victim of “spite and vindictiveness”.

At least one of MI5’s sources asserted that Moura was a lesbian – a surprising claim about someone whose biography contains such a long list of male conquests. If she was a lesbian, said another report, filed in 1951, then it could be “no more than 50 per cent of her personality”. Several sources remarked on her ability to down great quantities of gin, without showing any signs of being the worse for it.

Robert Bruce Lockhart first met Moura in 1918, when he was head of the British legation in Russia, during the revolution. She claimed to be an aristocrat by birth, though her father – Ignaty Zakrevsky, Nick Clegg’s great, great grandfather – was actually a lawyer who rose to be Russia Chief Prosecutor in 1894 only to die when she was still in her teens. When Bruce Lockhart met her, she was 26, and spoke good English. “She had a lofty disregard for all the pettiness of life and a courage which was proof against all cowardice,” Bruce Lockhart wrote in his Memoirs of a British Agent. “Her vitality, due perhaps to an iron constitution, was immense and invigorated everyone with whom she came into contact. Where she loved, that was her whole world…”

They were lovers almost at first sight. Their affair was dramatised in the 1934 film Secret Agent, starring Leslie Howard as Stephen Locke and Kay Francis as Elena Moura. It is not clear from his memoirs whether Bruce Lockhart knew that Moura was already married, with two young children. Her first husband, Count Johann von Benckendorff, owned an estate in Estonia. According to an MI5 report, he was murdered by a peasant in 1919.

The lovers were arrested in the panic that followed an attempt on Lenin’s life in 1918. Bruce Lockhart was soon released, but feared that their association had put her life in danger. He spent his 31st birthday, on 2 September 1918, at the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, pleading for her release.

The next day, he went to the Lubyanka on the same mission, and was promptly rearrested. He was deported a month later, as part of a prisoner exchange. To his surprise, Moura had been released before he was, having reputedly secured her freedom by seducing her investigating officer. As they said goodbye “my cup of unhappiness was full”.

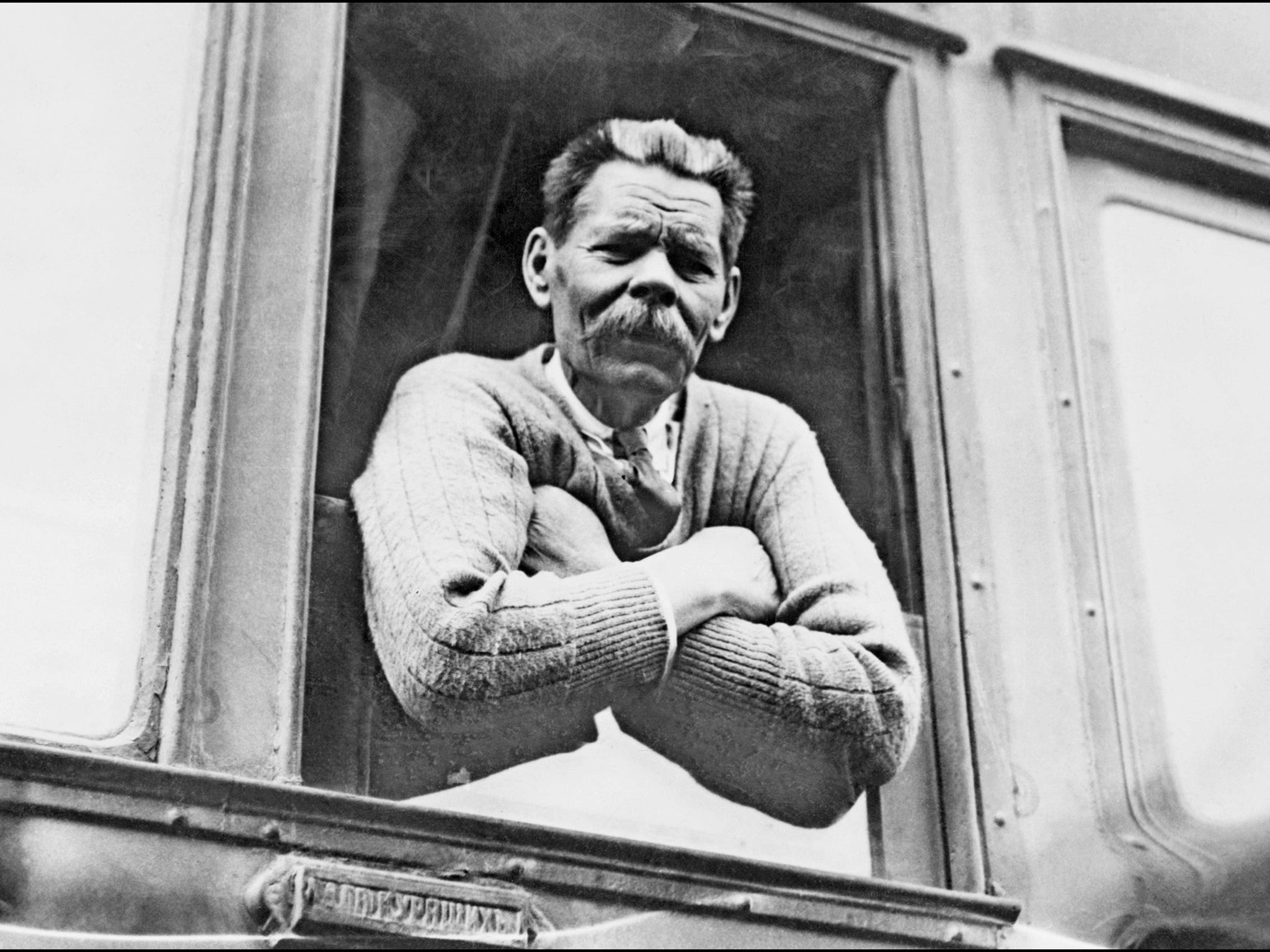

Returning to Petrograd, she applied for work as translator at the World Publishing House, run by Maxim Gorky, Russia’s greatest living writer and one of the few critics of the Bolshevik regime whom the police dared not touch. Moura was offered office work, but was soon on to something better. Gorky never liked to be without a woman in his bed. According to one of his biographers, Arkady Vaksberg, “his love for Moura was hopeless from the beginning”. Undeterred by a 24-year age difference, she soon moved into his half of the Gorky family home, while Gorky’s estranged pro-Bolshevik wife occupied the other half, with her new lover.

Gorky’s home was a port of call for foreign visitors, and Moura’s English made her an appropriate hostess. One visitor, in 1920, was H G Wells, who was put up for the night in the bedroom next to hers, but “lost his way” in the early hours, and wandered into her room, and into her bed. Gorky either did not know, or did not object. A year later, in 1921, Gorky arranged permission for her to leave Russia for Estonia, where one of the British intelligence reports noted that “for some reason” she married an aristocrat named Baron Nikolai von Budberg-Bönningshausen. They were together for barely a year, and divorced in 1926, suggesting that it was a marriage of convenience from which she secured Estonian citizenship.

In 1922, Gorky also emigrated, and she rejoined him in Berlin. For most of the 1920s, they lived together in Sorrento, in Italy, undisturbed by the Fascist authorities, until Gorky was overcome by homesickness and decided to make his peace with the Soviet regime. Moura refused to go back to Russia with him.

Her move to England may therefore have been motivated less by a desire to be with her niece, and more by the prospect of being left adrift in Europe without a lover or protector. In England, she had two ex-lovers. Bruce Lockhart did not want to resume their affair, but Wells was only too keen to. He wanted to marry her. She turned him down, though she lived with him for years. When he died, in 1946, he left her £4,000 – almost £120,000 in today’s money.

It did not take Moura long to become very well connected in the UK. Though British intelligence kept watch on her for years, opening her mail and tapping her telephone, they could not decide whether she was a threat to public security. What tipped the balance in her favour, in the long run, was the number of people in high places prepared to vouch for her, including both her ex-lovers, the wartime Solicitor General Lord Jowitt, and the Minister of Information, Lord Duff Cooper. The latter described her in 1942 as “an excessively tiresome old woman” (she was 50 by then) but “probably harmless”.

The spooks were not so sure that she was harmless. In the mid 1930s, Moura made a trip to Felixstowe, in Suffolk, to meet someone off a boat; the agents did not know why, and thought she might be up to something illicit.

She was still in touch with Gorky, though from 1932 onwards he never left the Soviet Union, and his household was under constant surveillance by Stalin’s police. Intelligence reports say she travelled in and out of the USSR on four occasions in four years, the last as Gorky lay dying in the summer of 1936. It was reported that she did not even need to apply for a visa, which suggests that the Soviet police wanted something from her – probably her collection of documents from the years she had spent with Gorky.

Her coming and going ignited the suspicions of Maurice Dayet, secretary of the French embassy in Moscow, who warned his British counterparts that she was “a very dangerous woman” who had had “two or three” interviews with Joseph Stalin. “You know perhaps that Stalin is fond of playing the accordion,” he added. “I have reliable information that she bought an accordion for him in London.”

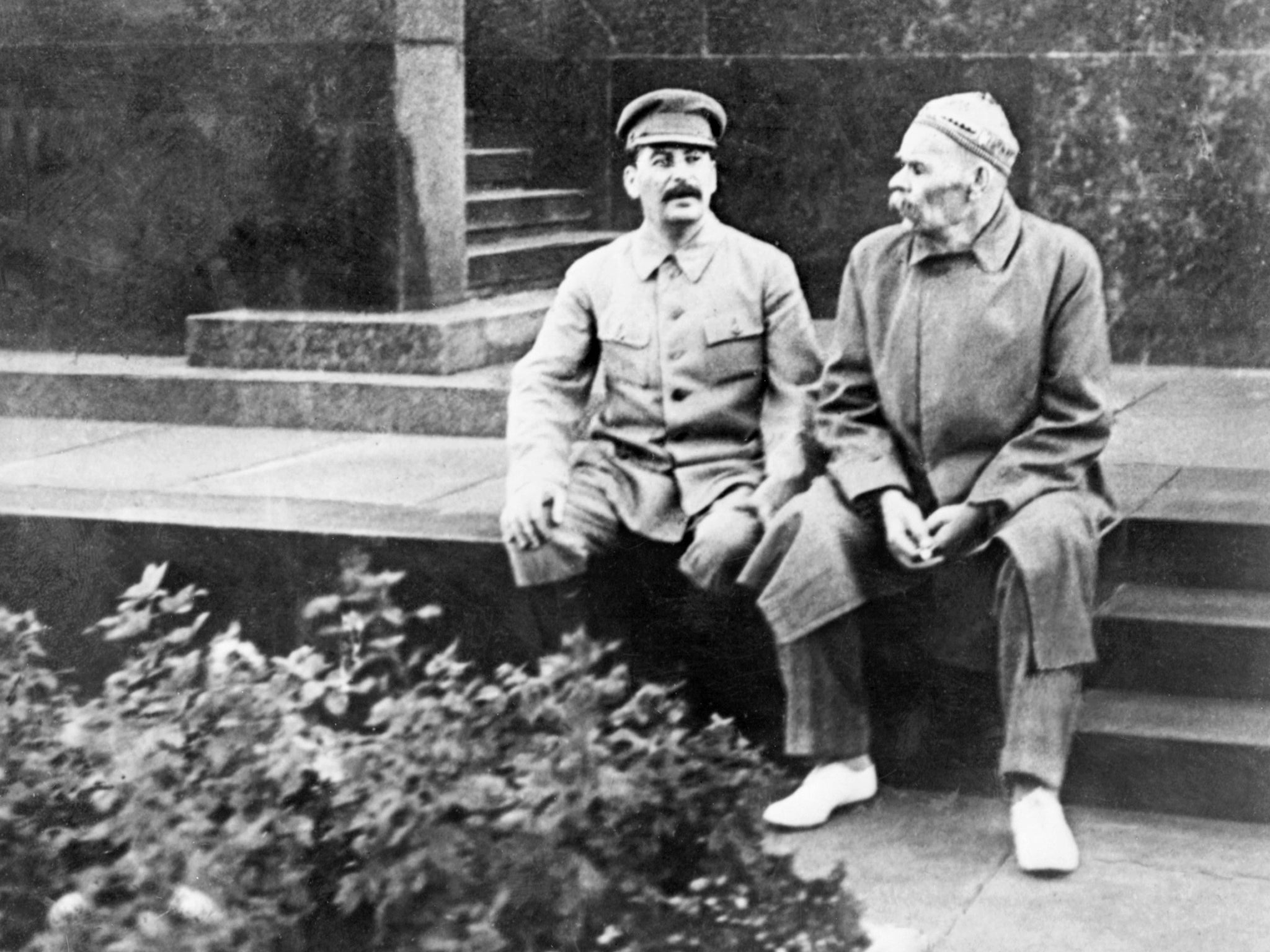

Actually, his information was not reliable. Stalin did not play the accordion, and Moura did not have interviews with him, but she was there when Stalin visited Gorky for the last time, on his death bed. “Who is that female monk dressed in black next to the patient’s bed?” Stalin snapped at a fellow visitor, Genrikh Yagoda, chairman of the NKVD, the dreaded Stalinist police. That would suggest she had never met the dictator before that day, though according Vaksberg, it was a joke. What we can certainly say is that on a day in 1936, four people were together in one room: a dying writer, two of the 20th century’s greatest mass murderers, and Nick Clegg’s great aunt.

As well as hearing from several quarters that the Countess was a Soviet spy, British intelligence also picked up rumours that she was in the pay of the Germans, but dismissed that after hearing from an informant who had witnessed her and H G Wells’s shocked reaction to the news in August 1939 that Stalin had signed a pact with Hitler. Moura Budberg would say that she was different from most Russian exiles because she “did not despise” the Soviet Union, but that betrayal jolted her, and it was probably what motivated her to apply to become a British citizen. That proved impossible during wartime: she did not become a British citizen until 1947. On the first occasion when she was able to vote, she voted Labour.

During the war, she worked with the Ministry of Information, headed by Lord Duff Cooper, and on a French language periodical published under government auspices. She infuriated Downing Street by getting involved with French exiles in a plot to oust General Charles de Gaulle from the leadership of the Free French. In April 1942, Winston Churchill’s personal aide, Sir Desmond Morton, wrote to the head of the secret service, Sir David Petrie, warning that “this appalling female … is a perfect terror at intrigue”. Sir David replied that the secret service knew a great deal about her, but considered her anti-Nazi.

Moura’s Soviet contacts were also considered useful during the war. On one occasion, she dined at the Savoy with the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, and the Soviet ambassador, Ivan Maisky. But as the Cold War set in, she was came under suspicion again. In 1951, MI5 was informed by a “very well-known person” that H G Wells’s family had known for years that she was a spy. Another document in the files reveals the well-known person’s name. It was the writer Rebecca West, who was not a disinterested observer: H G Wells was the undisclosed father of her son Anthony West, born in 1914.

In May 1951, British intelligence was hit by one of the biggest spy scandals in its history when two of its agents, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, suddenly disappeared, after the FBI had picked up evidence that Maclean was a spy. Burgess had been a much-loved guest in the dinner parties that the Countess Budberg held in her home in Ennismore Gardens, in Knightsbridge, where at least once he had got spectacularly drunk. MI5 tapped Moura’s phone and sent an agent to interrogate her at home, promising to share any information they obtained on her with the FBI.

Their agent found to his surprise that she was “an unusually intelligent and amusing woman … a quite outstanding personality [who] can drink an amazing quantity, mostly gin, without it showing any apparent slow-up in her mental processes.” Talking volubly, she told him that she knew that Burgess and Maclean were homosexual, believed that they were lovers, but did not know where they were.

She also dropped a bombshell by claiming that Burgess was “most devoted” to the art historian, Sir Anthony Blunt, keeper of the King’s pictures – who was, according to the Countess, a covert Communist. The astonished agent reported this to his superior, asking whether the allegation should be added to a file on Sir Anthony. The answer was “No”. Twenty six years later, Sir Anthony was sensationally exposed as a former spy.

An agent recorded that her visitors included a “Mr Weidenfeld”, whom other guests “addressed as George”. He was the founder of the small but growing publishing firm, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. It is likely that he met the Countess through one of his employees, Clarissa Churchill, niece of the Prime Minister and future wife of Sir Anthony Eden, who was listed by MI5 as one of the Countess’s social contacts.

When Weidenfeld visited Moscow in 1959 to sign up Russian writers, he took Moura with him, the first time she had seen the country of her birth in 23 years. She returned another six times between then and her death, aged 82, in November 1974.

The spooks never quite decided what to make of this extraordinary woman. In 1950, after they had delved into her finances for traces of Moscow gold, their agent reported: “She is mischievous in mind, being an ardent lover of intrigue [with] no particular loyalty except to herself. She does not live extravagantly except in so far as she drinks like a fish.”

A year later, after 22 years watching her on and off, they concluded that “there are very few items in her favour but the people who have vouched for her are persons of the highest integrity… So many and so conflicting are the reports about this woman throughout her career that it is a virtual impossibility to make an accurate estimate of the real weight of suspicion against her.”

Andy McSmith is the author of ‘Fear and the Muse Kept Watch, The Russian Masters under Stalin’ to be published by New Press, New York, July 2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments