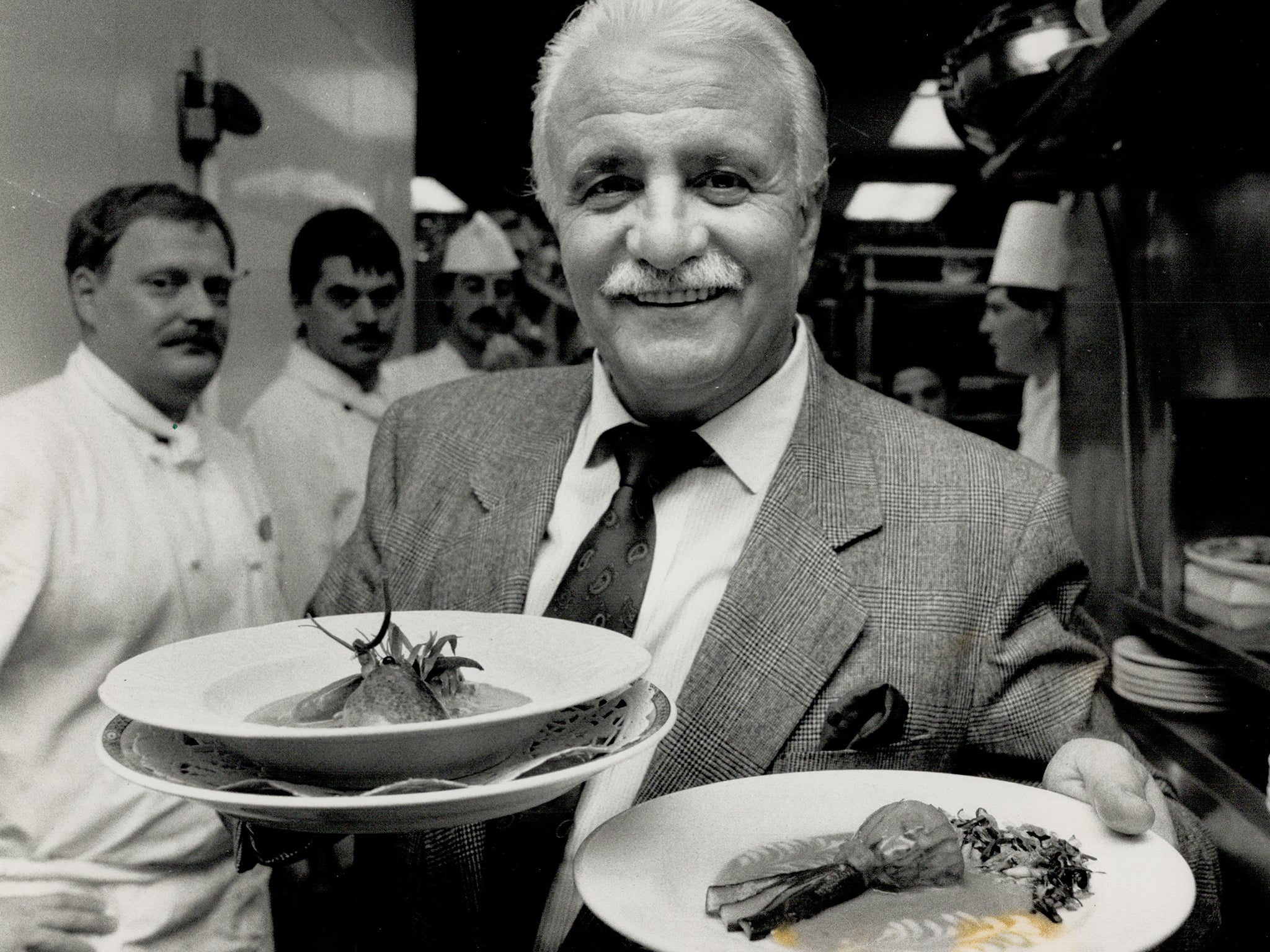

Roger Verge: Chef and cookery writer who championed nouvelle cuisine but was also highly accessible for home cooks

A keen collector of contemporary French art, Vergé was an interesting and genuinely nice man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With his matinee idol looks, flair and warm personality, Roger Vergé was a great poster boy for the nouvelle cuisine movement that dominated the restaurants of France from the 1970s to the late ’80s. His personal manifesto was called Ma Cuisine du Soleil, and was translated and adapted in 1979 by Caroline Conran, who did the same service for several of the movement’s chefs, giving them the wide currency they enjoyed in the English-speaking world.

Though Cuisine of the Sun contains mostly Provençal recipes from Vergé’s Michelin 3-star restaurant Le Moulin de Mougins, near Cannes, his own birthplace was Commentry, in the Auvergne, in what is almost the centre of France, and has a very different cuisine. His father was a blacksmith “during the day”, he wrote in the foreword, “but in the evenings he tilled God’s earth” and brought his mother flavourful, aromatic vegetables for the table.

But Roger actually learned to cook at the age of five, standing on “a small wooden bench” watching his aunt Célestine at the stove; she is the dedicatee of several of his books. Though he wanted to be an airline pilot, he was apprenticed in 1947, aged 17, to a local chef, Alexis Chanier, at Restaurant le Bourbonnais.

He obviously showed talent, as his next employers were grand Paris establishments, La Tour d’Argent and Plaza Athénée. He then travelled to North Africa, working first at Mansour de Casablanca in Morocco and then at L’Oasis in Algiers, and moved on to a job with an airline catering service in Kenya.

Returning to Europe, his first real exposure to southern French food came when he did a stint at the Hôtel de Paris in Monte Carlo and then moved to the Var, working at Le Club de Cavalière at Le Lavandou, which had two Michelin stars. While in these posts, he managed to get away for several months each year to the Plantation Inn in Ocho Rios, Jamaica.

How then, did he become the face of Provençal cooking and make its style and substance his own? “I think he simply fell in love with it,” Caroline Conran told me. In the summer of 1969, with his second wife, Denise, he renovated a 16th century olive mill at Mougins, near Grasse, in the hills above Cannes. At Le Moulin de Mougins he served the Provençal dishes he adored, but sometimes tinged by the flavours of his travels.

In North Africa he had learned to like combining fruit with savoury tastes, even to the point of flavouring oysters with orange (which seems less odd when you think about the more usual squeeze of lemon). He literally gingered up some of the standard dishes of the French repertory, while he introduced some distinctly non-haute cuisine items to the menu, such as a pig’s trotter and his own version of the local soup made from rockfish and very small crabs.

Vergé was a brilliant cook and a terrific host. It is no surprise that he got his first Michelin star the next year; the second came in 1972 and the third in 1974. He was now officially one of the best chefs in the world, but the greeting in the restaurant remained genial and unstuffy. As Mougins was only a 15-minute drive from Cannes, the film festival provided a steady stream of celebrities to be photographed with the moustachioed chef with the dazzling smile.

Though Le Moulin was informal, had plenty of tables on the terrace and the building, incorporating the old olive-press, was unintimidating, the Vergés decided in 1977 to open what they called a more accessible restaurant, L’Amandier de Mougins, just down the road, which had more Provençal and Niçois dishes, such as stuffed courgettes, artichokes Barigoule and salad mesclun, and at lower prices. L’Amandier does not have rooms, as does Le Moulin, but housed Vergé’s cooking school. It rapidly acquired two Michelin stars of its own, making Vergé the chef with the most Michelin stars (five) in all France. Moreover, his kitchens became a nursery for the culinary stars of the future, including Alain Ducasse (now the starriest of all), Jacques Maximin, Jacques Chibois, David Bouley and Daniel Boulud.

Vergé was associated with other pioneers of the nouvelle cuisine such as Paul Bocuse, Michel Guérard and the Troisgros brothers, but he became a sort of spokesman for Provençal cuisine, which he called “la cuisine heureuse”, happy cooking. It is, he said in the preface to his first book, “the antithesis of cooking to impress – rich and pretentious. It is a light-hearted, healthy and natural way of cooking which combines the products of the earth like a bouquet of wild flowers from the meadows.”

In 1982 he became partners with Bocuse and Gaston Lenôtre in opening a pair of restaurants at the France Pavilion in Disney’s Epcot Center near Orlando, Florida. The downstairs dished up cuisine bourgeoise, while the fancier first floor was (a little puzzlingly) called Bistro de Paris. The business arrangement ended in 2009. Vergé had retired from Mougins in 2003.

In 1985 he had stirred up (with a nouvelle cuisine sauce spoon) a restaurant-world fuss, remarking to a magazine that nouvelle cuisine had become “a joke. It is nothing serious. Now it looks Japanese: large dishes, small portions, no taste, but very expensive.”

Much though some of us agreed with him, he soon retreated (in a later interview with Nation’s Restaurant News): “We experimented with lighter sauces, new vegetables, fruit and meat combinations. But we already understood the basics. We had learned early. Our palates had already been conditioned.”

A keen collector of contemporary French art, Vergé was an interesting and genuinely nice man. History will be kind to him, if only for the reason given in Conran’s preface to her adaptation of Cuisine of the Sun: “Roger Vergé, of all the master-chefs working in France today, is probably the one whose ideas are most accessible to home cooks… he has never lost sight of the fact that cooking should be a pleasure – a celebration of wonderful ingredients, cooked in a simple and practical way that will not overtax the cook and leave her (or him) too exhausted to enjoy the meal.”

Roger Vergé, chef and cookery writer: born Commentry, France 7 April 1930; married firstly (marriage dissolved; two daughters), secondly Denise Regnault (one daughter); died Mougins 5 June 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments