Passed/Failed: An education in the life of Nicholson Baker, the American essayist and author of 'Vox' and 'The Fermata'

'I was obsessed with cycling and speed skating at school'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

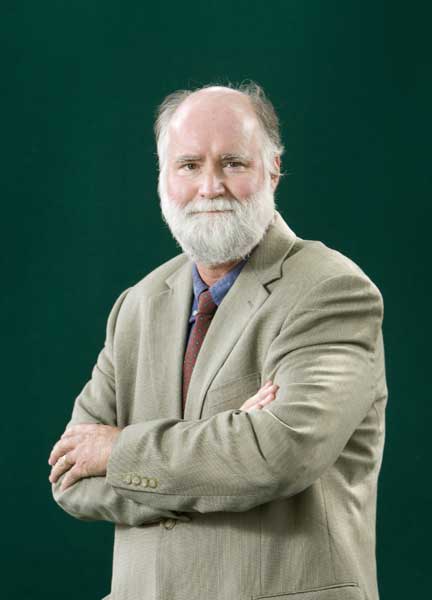

Your support makes all the difference.Nicholson Baker, 52, is the author of Vox, the novel about telephone sex that Monica Lewinsky supposedly gave to Bill Clinton. Other novels include The Fermata, the story of a man who can stop time, and, just out, The Anthologist. His non-fiction includes Human Smoke: The Beginnings of World War II, the End of Civilization, which came out last year.

After I got into a verbal conflict with another child at nursery school, the teacher gave me a life-size inflatable clown so that I could take out my aggression on it. I pushed it very gently and it went down and came up and I realised: "There is no way of winning against this clown!" I only got into trouble once at my nursery school in Rochester, upstate New York.

Then I went for a year to a private kindergarten. My mother paid the tuition fees by painting for the kindergarten a circular mural with pelicans, polar bears and seals.

I went to Martin B Anderson School Number 1 – all schools had numbers – for four years. Then voluntary integration came in and I volunteered to be part of this early experimental programme.

For two years we were bussed to Clara Barton School Number 2 in the heart of the city. I was part of a tiny white minority and had a really good time. We had to pick a book from a list and write a series of lessons as if we were the teacher. I made vocabulary quizzes and essay questions from Lord of the Flies but nobody did my lessons.

Then I went to Francis Parker Number 23 school for a year. I was obsessed with cycling and speed skating and didn't pay much attention in class. And then, at 13, I had a year at Monroe Junior High School, where we built a model of the Globe Theatre and everyone had to swim naked – very traumatic.

During a time of great excitement in public education, a new high school had been founded, the "School Without Walls". All of us had to invent our own programmes. If you were interested in designing a rocket, you would get in touch with an engineer. I ended up studying algebra in the attic of a church, and I had a physics class taught by a blind student at the university who had all the equations in his head. I realised I hadn't read a single book for a whole year and so attended literature classes at the university.

There was a year, at least, when I just cycled around. There were no grades, of course. I typed up my own "transcript" – the official record of what you've done. I tried to be truthful.

I wanted to be a bassoonist and to compose music in the style of Stravinsky and Bartok. Still in Rochester, I spent a year as a bassoon student at Eastman School of Music. I decided I was a failure as a composer and wanted to be a writer. I transferred to Haverford, a Quaker college in Philadelphia, and read English literature: Milton, Spencer, George Eliot's novels. I also took French, German and Latin and tried to catch up. I took a year and a half off and went to Paris and that's when I started writing fiction. I wrote a long story about a trombonist which ended up in The Atlantic, an American magazine, several years later.

They were good teachers at Haverford and, once I was at a place where they gave grades, I wanted good grades. My GPA – Grade Point Average – was 3.9; the highest possible was 4.0. I was there for four years and then took a class to be a stockbroker. I was a stockbroker for a week and a half; I sold some stocks to my bassoon teacher, my uncle and myself – and developed a psychosomatic illness.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments