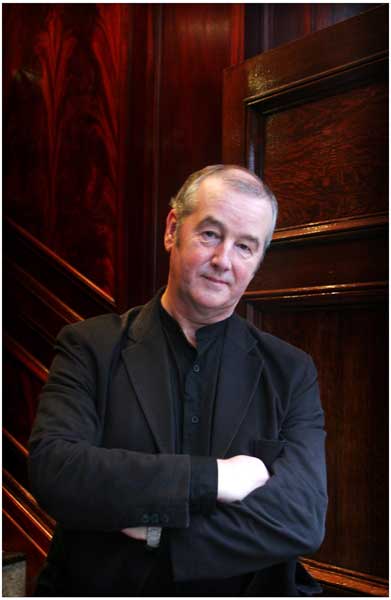

Passed/Failed: An education in the life of David Almond, the award -winning children's author, screenwriter, and playwright

'My teacher said I'd never be a writer'

David Almond, 58, won the Whitbread Children's prize and the Carnegie award with his novel Skellig, which he has adapted as a radio play, a television film, a DVD, an opera and a play opening at the Bloomsbury Theatre in London on 15 December. He won the Whitbread award again with The Fire-Eaters. The Savage and Jackdaw Summer came out last year.

There were rumours of ghosts and spirits roaming St John the Baptist Catholic primary in Felling-on-Tyne, Newcastle, a dark-seeming place built of stone. The toilets always seemed very sinister but some of the teachers were the opposite. I remember a very kind teacher, Miss McShane, giving me a book as a prize and I remember the feel of the book in my hand.

I was quite happy there. I don't remember it but people say I was creative with Plasticine; in my books I write a lot about making things in clay. I remember children being caned for not learning the catechism, the list of questions and answers that is part of being a Catholic. I got caned for dropping my pencil.

I was there until I was nine, when my parents sent me to a private Catholic prep school to make sure I passed the 11-plus. St Aidan's was a Christian Brothers' school; it has a bad reputation but I liked it a lot. The teaching was incredibly formal. You learned dates by heart and how you should address a Duchess and what the wife of a baron is called... this was for kids from Tyneside!

I passed the 11-plus and went to St Joseph's in Hebburn, the first co-educational Catholic grammar in the North-East. For the first couple of years I was happy but then things went downhill; I found the atmosphere unsympathetic. It was very regimented with a lot of corporal punishment – for girls, too. One of the first things I saw was a teacher going down a line of children, who were queuing for lunch, with a strap to keep them in order.

My father died during the year of my O-levels and I didn't remember any of the teachers saying anything to me about that. I was seen as a massive failure but got all the O-levels I took. I did okay at my A-levels, which were English, French and history. I saw myself as a writer and was reading a lot at home. English A-level was done in a very dry way – but one day the teacher came in and read TS Eliot's "The Waste Land". It was electrifying.

I remember reading The Third Eye, amazingly written claptrap by "Eastern guru" Tuesday Lobsang Rampa, who turned out to be a fake, a plumber from Devon. I spend much of my teenage years trying to travel in the astral plane but Gateshead library wouldn't give me the book about it.

I applied to six universities and got six rejections; I discovered later this was because of the reference given by the headmaster. Next year I applied to the University of East Anglia and got in to read English and American literature. It was fantastically well taught and very stimulating for a budding writer; literature felt like something you didn't study but took part in, a living tradition. I got a 2.1.

In the fifth form, a teacher had asked, "What do you want to be?" I couldn't say "novelist", so I said, "I want to be a journalist." He just laughed and said I had no chance. Every time I get something published, I still think of him and a voice at the back of my head says, "There you are!" And when I stepped on stage for my first Whitbread award, I heard myself saying, "There you are!"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments