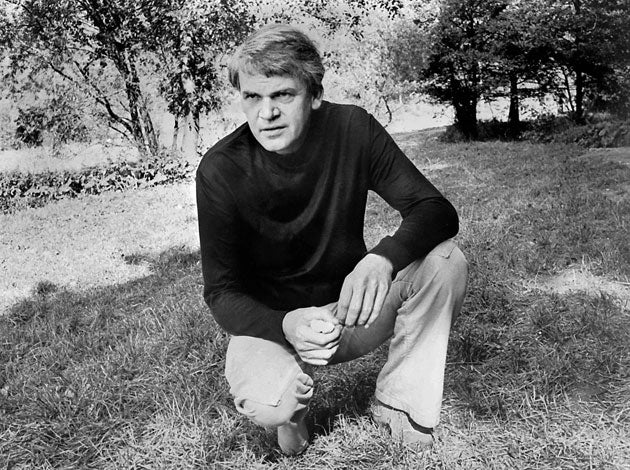

Milan Kundera: Unbearable lightness of being under-appreciated

A new novel from the 85-year-old exile is a cause celebration in the West, less so among the Czechs he left behind

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Until this week, Milan Kundera was in some danger of being forgotten.

A resident of Paris since 1975, a French citizen since 1981, writing in French rather than his native Czech, one of the great figures of world literature had all but vanished into the French capital. His most recent novel, Ignorance, came out as long ago as 2000. He welcomes interviewers as about as warmly as Samuel Beckett used to.

With the world captivated by news of Harper Lee’s sequel to To Kill A Mockingbird, the impact of the announcement by Faber & Faber that a new Kundera novel, The Festival of Insignificance, is to be published in the UK in June was perhaps less than it might have been. But this is some moment. The book has already appeared in Italy, France and Spain, topping bestseller lists in each country. One French reviewer called it “magnificent, sunny, profound and funny” – words that for many will bring back the charm, the magic and the delirious eroticism of Kundera’s most famous book, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, published in 1984.

Czechoslovakia (as it then was), like the rest of the Warsaw Pact, was for the West a grim, grinding zone of ideological correctness, Soviet menace and pickled gherkins. Kundera, now 85, opened our eyes to a sophisticated, richly cultured, deeply ironical country which, as he once said, “for a thousand years was part of the West”. That the wellsprings of his work are receding into the past – the post-war communist tyranny in Eastern Europe and the effort to flee from it or otherwise transcend it – don’t make the prospect of a new novel from him any less intriguing. If anything, they make it more so.

Born, in 1929, into a middle class family in Brno, his father a pianist who was a great influence on him, Kundera studied literature and film in Prague. A teenage member of the Communist Party, after the war he shared the slow and painful disillusionment of his generation as the influence of Stalinist conformity and paranoia steadily bore down on the life of a city which, many years later, he described as possessing “an extraordinary sense of the real … a provocative simplicity. A genius for the absurd. Humour with infinite pessimism.”

He was expelled from the party in 1950 after a trivial incident which inspired the plot of his first novel, The Joke. A clever, dashing and popular young party member writes a cheerful postcard to a female classmate which reads, “Optimism is the opium of the people! A healthy atmosphere stinks of stupidity! Long live Trotsky!” for which he is thrown out of the party. Kundera himself was readmitted in 1956 then expelled again in 1970. And though aligned with the nation’s other dissident intellectuals, he preserved his communist faith longer than most, arguing with the playright and future President Vaclav Havel that the system could be reformed. Eventually resigned to the fact that it could not, he went into exile in France in 1975.

And it was in exile that his genius bloomed, producing a string of luminous, elusive, subtle, enigmatic novels which reflected a literary identity squarely in the modernist line of James Joyce and Franz Kafka but with an inflection all his own. “He has brought Eastern Europe to the attention of the Western reading public,” a rare interviewer, Olga Carlisle, wrote in 1985, “with insights that are universal in their appeal. His call for truth and the inner freedom without which truth cannot be recognised, his realisation that in seeking truth we must be prepared to come to terms with death – these are the themes that have earned him critical acclaim.”

Faber & Faber say the new book is “a wryly comic yet deeply serious glance at the ultimate insignificance of life and politics, told through the daily lives of four friends in modern-day Paris”. Like all Kundera’s work, it reflects his own ambivalence and diffidence about political commitment, his belief, as he told Carlisle, that “the temptation of preaching … may be quite appealing, but for literature it is deadly. Only a literary work that reveals an unknown fragment of human existence has a reason for being. To be a writer does not mean to preach a truth; it means to discover a truth.”

One of the reviewers of the Italian translation, Alessandro Piperno, noted that Kundera “has difficulty falling in love with an opinion. This makes Kundera a surprisingly out-of-date writer. Today everybody has an opinion about everything … Kundera treats strong opinions warily. I imagine that this derives from his old battle against totalitarianism. It’s a real obsession that conditions everything he writes.”

Another Italian critic, Emilio Fabio Torsello, noted that the theme of universal insignificance pervades the work. “Everything ceases to matter: gestures, words, lies, jokes, absence, lost love, death. Everything is insignificant for Kundera: the individual, the very lives of his ordinary, unimportant characters; but equally insignificant and almost clownish are the grand figures like Stalin and Kruschev whom Kundera evokes in the novel, as light as a feather which all of a sudden someone notices falling from the high ceiling of a ballroom. It’s a crowded scene – crowded with figures unable to leave a trace either in everyday life or in history.”

The melancholy of impermanence saturates the novel, a rootlessness that links him to other great literary exiles such as Beckett and Joyce. And this in turn reflects his tormented relationship with his homeland, which he is said to visit rarely, and always incognito.

Kundera’s high reputation, which has often seen him tipped as a Nobel Prize candidate, does not extend to his native land. This was due, Dan Bilefsky wrote in The New York Times, to the “decidedly central European distaste for others’ success, and particularly for that of Kundera, who has long held himself aloof from the nation of his birth.” Bilefsky was writing in 2008, when Kundera was denounced in print for allegedly having betrayed a western spy to the communist authorities while a 21-year-old student. The agent, Miroslav Dvoracek, served 14 years in jail, including hard labour in a uranium mine.

Kundera denied the charges immediately, but they fed into pre-existing dislike of the voluntary exile. Petr A Bilek, professor of comparative literature at Kundera’s alma mater in Prague, commented: “The revelation that Kundera denounced someone is seen by Czechs as vindication of their belief that he has been betraying them for years. His fellow dissident writers have long tried to dismiss him as someone who writes intellectual pornography for mediocre Western readers.” The Unbearable Lightness was only translated into Czech 25 years after its success in the West, and was seen as insulting to former dissidents. It sold a mere 10,000 copies. Sales in English and other languages run to hundreds of thousands.

Kundera’s refusal to take a political stand has rendered him a lonely figure, one who sees through the partisan’s posturing to the emptiness beyond. “There is a thing, D’Ardelo, which I have wanted to speak about for some time,” the main character of the new book declares. It is “the value of insignificance … Insignificance, my friend, is the essence of life. It is with us everywhere and always. It’s present even where nobody wants to see it: in horrors, in cruel battles, in the worst disasters. It often requires courage to recognise … But it’s not enough to recognise it, it’s necessary to love it … Breathe, D’Ardelo, my friend, inhale this insignificance that surrounds you: it is the key of wisdom, the key of contentment.”

Life In Brief

Born: 1 April 1929 in Brno, Czechoslovakia.

Family: father, Ludvík was a concert pianist and mother Milada, a labourer. Married to musician Vera Hrabankova.

Education: studied literature at Charles University in Prague and film at the Academy of Performing Arts.

Career: lecturer in world literature at the academy in 1952. First novel, ‘The Joke’, published in 1967, ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Being’ in 1984; ‘The Festival of Insignificance in June 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments