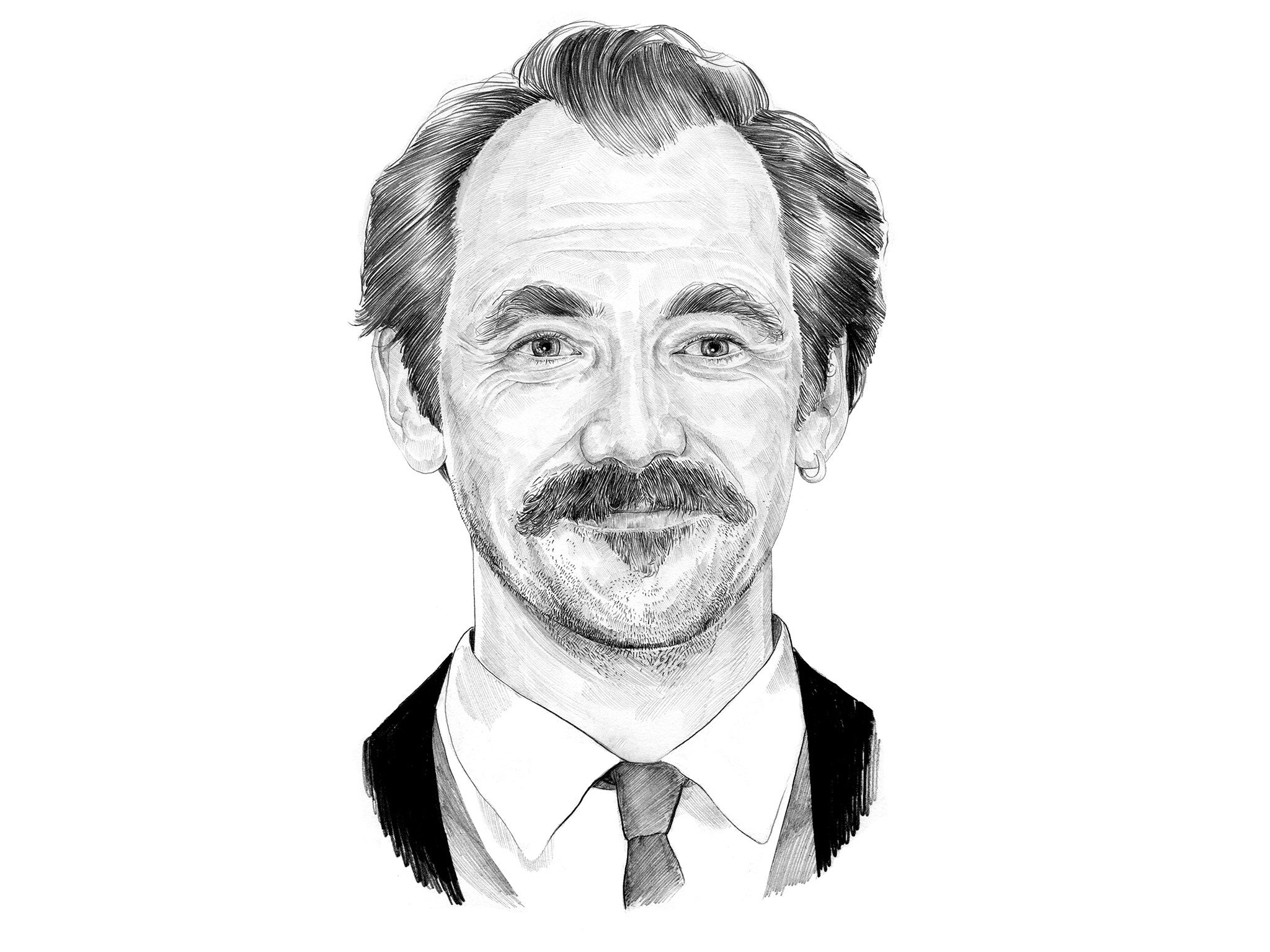

Mark Rylance: King of stage claims small screen

At the Globe and in 'Jerusalem', he was theatre's ruler. Now Cromwell has let television viewers in on the secret

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.That four million people tuned in to watch Wolf Hall this week – an astonishing figure for a costume drama – was testimony to the place that Hilary Mantel’s Tudor court-set novel, and its sequel, Bring Up the Bodies, occupy in the literary and wider cultural landscape.

With combined UK and US sales of the two books now around the two-million mark, Mantel has turned historical fiction, once a relatively niche genre, into a mass-market phenomenon. She has shown that, treated with such originality, there is no period in English history that grips the imagination quite like the tumultuous reign of Henry VIII.

So when Mantel’s “biography” of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister, was dramatised for TV, it was a star vehicle only in as much as the story itself was the star. While Damian Lewis, playing Henry, came to his role trailing clouds of TV glory thanks to his prominence in the hit conspiracy thriller Homeland, and Jonathan Pryce (Cardinal Wolsey) has screen credits by the yard, Mark Rylance, as Cromwell, is an actor whose brilliance, until now, has been known about far more by theatre-goers than film or TV audiences.

For a lot of actors, it’s all about the screen – Damian Lewis himself, for example. Then there are those – Benedict Cumberbatch springs to mind – who at least start off straddling screen and stage. Finally there is a group that appears on the former from time to time but whose real calling is the latter. For many people, they are an elite within an elite. Simon Russell Beale and Fiona Shaw fall into this category, both of them frequently referred to as the greatest actor/actress of their generation. It’s the same with Rylance, whose stage work over the past 20 years has earned him just that accolade in many quarters but who, until now, could walk down the street largely unnoticed.

“I think Mark has had mixed experiences with directors on film,” says Peter Kosminsky, the director of Wolf Hall, and also the director of the 2005 one-off TV drama The Government Inspector, for which Rylance won a Bafta playing David Kelly, the UN weapons inspector. “Of course, the stage is very much an actor’s medium and Mark is the definitive, consummate stage actor. Film is primarily a director’s medium and Mark may have found his freedom of thought and expression constrained. But, when he has appeared on film, his performances have tended to be extraordinary.”

Such was the consensus around the first episode of Wolf Hall. “Mark Rylance’s eyes glistening with sadness and acuity produce a Bafta-winning performance by themselves,” was The Times’s verdict. The Independent described Rylance’s performance as “imperious”. The word The Daily Telegraph used was “riveting”. According to The Guardian, he was “hypnotic, understated but totally screen-owning”. Rylance has long dazzled in his own firmament. Now, at 55, he stands to become something else again – a household name, a status he certainly hasn’t sought out. “Mark is a pretty private person,” says someone who has worked closely with him for many years, and that tallies with Rylance’s original urge to act (shared by many in the profession) which was by way of a reaction to his intense shyness. “I couldn’t speak until I was six,” he has been quoted as saying.

Born David Mark Rylance Waters (there was already a Mark Waters in Equity) to parents who were both teachers, Rylance was two years old when the family moved from his native Kent to the United States, settling first in Connecticut and then in Wisconsin. He was an enthusiastic participant in plays at the University School of Milwaukee before returning to the UK to take up a place at Rada, where his contemporaries included Kenneth Branagh and Fiona Shaw. Spells at the Glasgow Citizens Theatre and the RSC followed, but it was the 10 years he spent from 1995 to 2005 as artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre that really established him. He directed and acted in every season, bringing an energy and an imagination to bear that were there for all to see in 2009 when he took on perhaps his most famous stage role, that of Johnny “Rooster” Byron, the bucolic rebel who defies all authority in Jez Butterworth’s hymn to English non-conformism, Jerusalem – a huge hit in both London and New York.

Jerusalem cast member Lucy Montgomery recalls Rylance’s leadership qualities. “He had this initiation rite which he said came from a native American tradition. He had a sack in which he poured a mixture of things – cocoa powder, whisky, and we wrote down our wishes for the production on pieces of paper and they went in the sack too. It hung at the back of the stage for the whole of the run.” The sack did the trick, so much so that when the run ended the producers handed Rylance a hefty bonus. “He obviously could have kept the money to himself,” Montgomery recalls. “Instead he distributed it round the whole cast. We got 100 quid each. He’s just such a caring guy.” Similar things happened on the Wolf Hall set, where, according to Kosminsky, Rylance “arranged special Tudor-inspired treats at tea time for the whole crew – every day, at his own expense”.

Asked about Rylance’s technical gifts, Kosminsky describes how “Mark can be wonderfully still on camera but his stillness is never empty, blank”. He adds: “Of course you know what your next line is from the script. The hardest part of the job is listening, making it look and sound as if you have no idea what you’re going to say until you hear the feeder line. Mark listening is riveting. So much going on below the surface. So many textures, undercurrents.”

In acknowledging these hidden depths in Rylance’s portrayal of Cromwell, press and public have made a certain amount of the tragedy that struck Rylance in 2012 when the elder of his two stepdaughters died at the age of 28 from a brain haemorrhage. There is a bitter twist in the fact that in Wolf Hall Rylance is playing someone who himself endures the death of his wife and daughters, but the idea that his performance is somehow even more convincing as a result doesn’t really stack up. What we do know is that the loss of his stepdaughter interrupted Rylance’s career, causing him to pull out of a role he had performing a section of The Tempest at the opening ceremony of the London Olympics. (Kenneth Branagh stepped in.)

Nataasha was the elder of two daughters that Rylance’s wife of 25 years, the composer and fellow director Claire van Kampen, had with her first husband. It says something about Rylance that Chris van Kampen, an architect, became “one of my best friends”, according to an interview Rylance gave to the Sunday Times recently. The two men – first and second husbands of the same woman – go on a walking holiday every year. Rylance told The Sunday Times that Nataasha and her sister Juliet – small children when Rylance came into their lives – “would accept nothing less than that we all became friends. They were adamant”.

Rylance is clearly a man who manages to live by his own lights while taking everyone along with him. And he is perhaps reconciled to his followers rapidly increasing in number, not just through Wolf Hall, but through accepting the role of the Big Friendly Giant in Steven Spielberg’s film version of the Roald Dahl classic, due out in 2016. Giants of acting don’t come much bigger or friendlier than Mark Rylance.

A life in brief

Born: 18 January 1960, Ashford, Kent.

Family: His parents were Anne and David Waters, both English teachers who worked in the United States. Married to Claire van Kampen, a director and composer.

Education: Attended Rada in London on a scholarship, after auditioning with a monologue from Hamlet.

Career: Joined the RSC and performed at the National Theatre before spending 10 years as the first artistic director of the Globe. Won three Tony Awards.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments