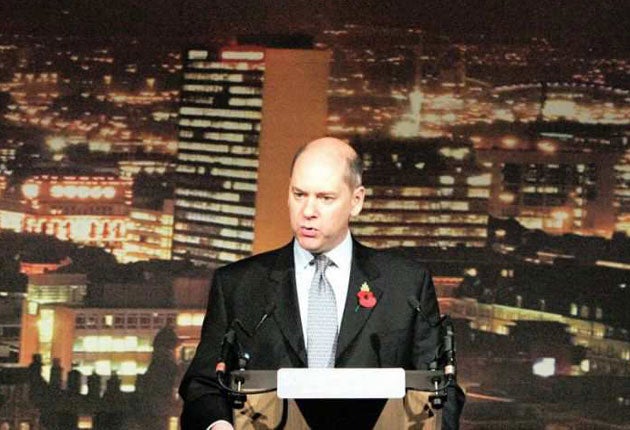

Jonathan Evans: The spy who came out from the cold

Time was when we didn't even know the name of the head of MI5. The latest incumbent shows how open the secret service has become

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jonathan Evans looks like a normal human being. With that reassuringly open face, bald head and the smart but not expensive clothes, you could imagine him as the manager of a medium-sized factory in the Midlands. The real-life head of MI5 – who set an unexpected precedent this week by being the first director general to call journalists to his office for an on-the-record briefing – does not remotely resemble any of the characters from the BBC drama Spooks.

In Spooks, the heroes take risks and bend rules to produce quick results, but those who know Evans say he is not the risk-taking type. He is more likely to stay at his desk for hours on end, methodically sifting data to analyse what can be safely deduced from the scattered details. In private, he is said to have a pleasant, approachable manner, and comes over as someone who is more reliable than heroic.

This matters, because some very peculiar people have crawled out of MI5 during the three decades that Evans has worked there. It is a fast-growing organisation whose principal task is to ensure that atrocities such as the 7 July suicide bombings are never repeated. They also keep watch over the Irish nationalist splinter groups.

It would not be reassuring to think that this organisation was run by someone like Peter Wright, who was the only identifiable public face of MI5 20 years ago, in the days when serving officers were never identified. Wright stepped into the open because he was aggrieved about his pension, and defied the Official Secrets Act by writing his memoirs.

He was a weird, paranoid, embittered man who was convinced that the former director general of MI5, Sir Roger Hollis, was a Russian spy, and claimed that 30 of his fellow officers had plotted to bring down the Labour government in the early 1970s. In the more open regime run by Evans, you can access the official MI5 website, where both these allegations are emphatically denied.

There was also Michael Bettaney, a middle-ranking MI5 officer who tried to set fire to himself during an office party and told guests that he would rather be working for the Russians than the British. Nothing was done until the other spy organisation, MI6, found out that Bettaney was, in fact, offering secrets for sale to the KGB.

Then there was David Shayler, who went public about his work in MI5 in the 1990s. He now claims to be the Messiah. Even Stella Rimington – the first woman director general of the MI5 and the first whose appointment, in 1992, was made public – came over as a strange individual, though she had a reputation as a very sharp, disciplined professional. Her memoirs reveal a history of migraines and claustrophobia.

This makes it all the more remarkable that Mr Evans gives off an air of normality after spending the whole of his working life within this claustrophobic world. He joined MI5 after he graduated in classical studies from Bristol University in 1980. It can be assumed that he spent his first five years scouring the British political landscape on the lookout for Russian agents or others out to subvert parliamentary democracy.

In those days, MI5 was keeping watch over a lot of people whose only offence seemed to be that they were campaigning against the Thatcher government. They included union leaders, CND activists, and future Labour ministers such as Harriet Harman. But the MI5 website claims: "We have never investigated people simply because they were members or office-holders of trade unions or campaigning organisations, but subversive groups have in the past sought to infiltrate and manipulate such organisations as a way of exerting political influence. To meet our responsibility for protecting national security, we therefore investigated individual members of bona fide organisations."

In 1985, Evans switched to working on ways to protect classified information in different government departments. His official biography also notes that he had "various postings in Irish-related counter-terrorism during the late 1980s and 1990s". He also spent two years in the Home Office, advising on security arrangements for VIPs. By 1999, he was specialising in the threat from international terrorism. He was appointed director of international counter-terrorism just 10 days before the 11 September attacks in New York.

That atrocity gave a whole new meaning to MI5's existence. After communism had collapsed and the IRA had declared a ceasefire, there were questions to be answered about whether splinter groups such as the Real IRA, malicious though they may be, were a big enough threat to justify keeping about 2,000 staff employed full time in MI5's swish Millbank headquarters.

Since September 2001, the organisation has enjoyed rapid growth. By 2011, its staff numbers will have more than doubled. Even in these relatively open days, the size of MI5's budget is a secret, but an idea of it can be gleaned from a Treasury note on the Single Intelligence Account, money set aside for MI5, MI6 and the GCHQ spy centre. The SIA has gone up from £1.25bn three years ago to £1.86bn in the current year, and will exceed £2bn in 2010-11. It is probable that MI5 is consuming the lion's share.

This explains the surprising high profile the new director took after his appointment in April 2007. With so much public money pouring into his organisation, and with the ever-present risk that one day a suicide bomber would slip beneath MI5's radar, he needs to keep public opinion on his side.

Potentially, the worst mark on MI5's reputation since 2001 occurred while Evans was deputy director general, when it emerged that they had had the leader of the 7 July suicide bombers, Mohammad Sidique Khan, under surveillance, but stopped watching him because they did not think he was a significant figure.

Evans made a point of answering this criticism in his first public speech as director general, when he addressed the Society of Editors in Manchester late in 2007. "The deeper we investigate, the more we know about the networks," he said. "And the more we know, the greater the likelihood that, when an attack or attempted attack does occur, my service will have some information on at least one of the perpetrators."

His next public relations problem was more farce than tragedy, when he had to hose down a rumour that MI5 had been plotting against the FIA president Max Mosley. The dominatrix who secretly filmed Mosley in a sado-masochistic sex session was married to an MI5 officer, who sold the story to the News of the World. Reportedly, Mr Evans thought it necessary to contact Gordon Brown and the Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith, to reassure them that MI5 was not officially involved in any operation against Mosley. The officer lost his job.

This week's foray into public relations has made Mr Evans a yet more familiar figure to the public, largely because of the accompanying photograph showing him without jacket or tie, with sleeves rolled up.

One very senior politician who has worked with Evans said: "I was surprised that he did that, though I think he did it well. Jonathan is an absolutely regular professional. I don't think he is versed in PR. I have always thought of him far more as a strategic planner and a highly practical intelligence collector and analyst. He is not a risk-taker."

But others think that Evans is taking a big risk by showing his face to the public. So far, it has paid off, but as one former member of the Commons intelligence committee, who thinks the secret service should stay secret, pointed out: "So far, thank God, we haven't had a tragedy on Jonathan's watch. But if there is one, people will say, 'Where's the director general?' They'll expect to hear his explanation. Then he may wish he had stayed out of sight."

A life in brief

Born: circa 1958. Little is known about his family life or upbringing thereafter.

Early life: Privately educated at Sevenoaks School in Kent, before attending the University of Bristol in the late 1970s and graduating with a degree in classical studies.

Career: Joined MI5 in 1980 and worked on counter-espionage investigations for five years before moving to protective security policy, which focused on the defence of classified information and policy reform. Transferred to counter-terrorism in the late 1980s, joining efforts to quell the Provisional IRA. He was appointed director of international counter-terrorism in 2001, just 10 days before the attacks of 11 September. In 2005, after Dame Eliza Manningham-Buller announced her intention to step down, he was promoted to deputy director general, and finally became chief in 2007.

He says: "I will continue to make MI5 as visible as possible. It is right that the public should understand the way we work, and the thinking behind the wider counter-terrorist strategy."

They say: "Here was a man who was clearly a quiet professional, someone who doesn't parade himself, who doesn't push his own personality upfront, but actually has been dedicated, committed to the service and the wider security issues for as long as I can remember." David Blunkett, former home secretary

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments