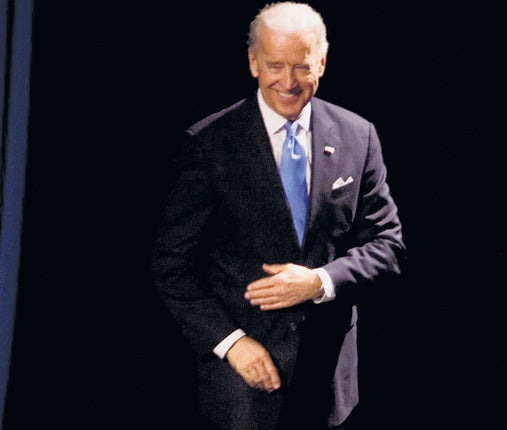

Joe Biden: The likeable joe

Garrulous and experienced, America's Vice-President is where he seems most at ease – at Obama's side but not at his heels

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The moment when Joe Biden began to metamorphose from senator into the future Vice-President can be precisely dated, to 26 April 2007, in the midst of one of those mostly forgettable TV debates between the candidates for the Democratic nomination the following year. Indeed, it may be traced to a single word.

Would he have the self-discipline to be president, the famously loquacious and gaffe-prone Biden was asked. Quick as a flash came the reply, a clipped and terse "Yes". The audience, well aware of the senator's propensity to give windy and interminable answers to the simplest of questions, howled with laughter – but the point was made.

Biden, of course, didn't win the nomination. That went to a charismatic opponent whom with typically engaging crassness, he had a few months earlier described as "the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy". But although he withdrew from the race after finishing a distant fifth in the Iowa caucuses that kicked off the 2008 primary season, Biden was generally adjudged to have fought an impressive campaign. Even more importantly, Barack Obama had quietly marked his card.

During that summer, candidate Obama told his defeated rival that he wanted him in the administration, should he win, either as secretary of state or vice-president. Biden hesitated, wondering whether either post was preferable to his current job as chairman of the Senate foreign relations committee. But when he was asked to be Obama's running mate, Biden again said yes. This week, it could be argued, the transformation became complete. On Tuesday evening the 47th Vice-President of the United States turned up 90 minutes late for dinner with Benjamin Netanyahu, the Prime Minister of Israel. Had this happened in an earlier Biden life, the delay would surely have been attributed to a scheduled five-minute speech that turned into a rambling and self-indulgent hour's worth.

Not now. Biden's tardiness was an angry and calculated response to the extraordinary embarrassment inflicted on the highest ranking visitor despatched by President Obama, leader of the country that is Israel's most vital ally. Hours earlier, the Vice-President was talking about a new opportunity for progress between Israelis and Palestinians – only for the former then to announce it would build 1,600 homes in East Jerusalem, whose future is perhaps the largest single obstacle in the way of a peace deal.

Diplomatic two-finger salutes don't come much cruder. But Biden, at least as far as can be judged from a 5,000-mile distance, made the best of a very bad job. He condemned the planned new settlements with characteristic bluntness, and then delivered his dinner snub. But in a speech on Thursday he made the case for peace, powerfully and without bitterness. Some will say he should have gone home on the spot. That, however, would be to ignore the reality of the US relationship with Israel. If these latest Israeli/Palestinian talks are stillborn, it won't be Joe Biden's fault.

One reason of course is that the man is so hard to dislike. Yes, he puts his foot in it on occasion, but in a buttoned-up city that can be refreshing. For years, Biden was living proof of the old adage that in Washington, a gaffe is when a politician by accident blurts out the truth. Since he became Vice-President his record has improved, but the old Biden sometimes resurfaces – as it did at the height of the 2009 swine flu scare. It wasn't just about going to Mexico, the epicentre of the pandemic, he opined to a TV interviewer, "It's if you're in a confined aircraft; when one person sneezes, it goes all the way through the aircraft." White House aides had to spend days dousing the ire of the already struggling airline industry.

But Obama knew exactly what he was getting when he selected Biden, rightly concluding that the pros outweighed the cons. Born in Pennsylvania to a Catholic family of modest means, Biden could connect to white working-class voters in rust-belt states in a way Obama never could. Aged 66 when he took office, Biden moreover had no further political ambitions of his own – removing one frequent complication to relations between a vice-president and his boss.

No less important (so it seemed at the time) was Biden's vast experience in the Senate. When he was elected in November 1972 at the age of 29, he was the youngest Senator in history. By the time he resigned in January 2009, he had just won a seventh term, making him the 14th longest-serving Senator in the country's history.

Of those 36 years, he spent 16 as chairman of the high-profile judiciary committee, before becoming the senior Democrat on, and later chairman of, the foreign relations committee. Biden might have been to the centre-left on domestic issues, but in international affairs he was – and remains – a liberal interventionist of the JFK mould. Like almost every Democrat, Biden voted against the first Gulf War in 1991, but became a passionate believer in US involvement in the Balkans to help Bosnia and then Kosovo. At one point, he called Slobodan Milosevic a "war criminal" to his face. In October 2002 he supported going to war again against Saddam Hussein, but by 2004 declared his vote had been a mistake.

Even so, he was popular with his Republican colleagues, often working quietly across the aisle with foreign policy moderates like Richard Lugar and Chuck Hagel. "I may be resigning from the Senate today," Biden declared in a surprisingly restrained farewell speech from the floor on 15 January 2009, "but I will always be a Senate man." As such, Biden appeared especially well placed to help to build the new era of political comity promised by Obama during the campaign. That this has not materialised was no fault of his; rather of the partisanship that poisons everything in Washington.

Today, the vice-presidency seems fitting climax to a career that, even had it finished in the Senate, would have been remarkable enough. The Biden story has also been one of hurdles and crushing setbacks overcome, both private and professional. There is the disaster even people in Britain know about: the plagiarising of then Labour leader Neil Kinnock that brought his 1988 bid for the White House to a humiliating end. Then there are the private agonies: the stutter that the youthful Biden had to overcome; the tragedy when his first wife and daughter were killed in a car crash a month after he was elected in 1972; and two bouts of brain surgery in 1988 to correct life-threatening aneurisms. Set against such events, all things are relative, even the present tribulations of the Obama administration.

Biden now is in his comfort zone. By all accounts he works well with Obama. He is an influential Vice-President – but not in the grim, secretive style of his predecessor Dick Cheney, perhaps the most powerful holder ever of the office. He has a very competent staff, and retains many close friendships on Capitol Hill. Indeed, those contacts are widely credited with securing passage of the President's bitterly contested $787bn economic stimulus last February.

His brief and workload stretch across the board. One moment Biden is handling the vetting and confirmation of Sonia Sotomayor, Obama's first nominee to the Supreme Court, the next he is checking that infrastructure money contained in the stimulus package was being properly spent – and this week he's been on a mission to Israel that would have been sensitive even without the settlements row, discussing not just Palestine but also Iran.

His most valuable role, however, is as in-house contrarian. Biden's frankness make's him an ideal devil's advocate – on Afghanistan for instance, when he made the case for a targeted anti-terrorist strategy, rather than the broader surge for which Obama ultimately opted.

He's not always right. But far more important, he has not emerged as a Cheney-like point of friction and resentment. This administration is working smoothly on the foreign policy front, with none of the open feuding that bedevilled the George W Bush White House. For that thank, in part at least, Joe Biden. "It's easy being vice-president," he likes to say, "like being the grandpa and not the parent." And of course, nobody minds if grandpa sometimes says something silly.

A life in brief

Born: 20 November 1942, Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Family: The eldest child of Joseph Biden Snr, a used-car salesman, and Catherine Finnegan. He has two brothers and a sister. His first wife Neila was killed along with their daughter in an automobile accident in 1972. He also had two sons with her. He remarried, to Jill Jacobs, in 1977. They have one daughter.

Education: He attended Archmere Academy in Claymont and the University of Delaware, where he gained a BA with a double major in history and political science. Graduated from Syracuse University College of Law in 1968.

Career: He was admitted to the Delaware Bar in 1969, becoming a public defender before starting his own firm. He was elected as senator for Delaware from 1973 until his resignation in January 2009, following his election to the vice-presidency under Obama. He unsuccessfully sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988 and 2008.

He says: "There is no space between the US and Israel when it comes to Israel's security."

They say: "The best thing about Joe is that when we get everybody together, he really forces people to think and defend their positions, to look at things from every angle, and that is very valuable for me." Barack Obama

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments