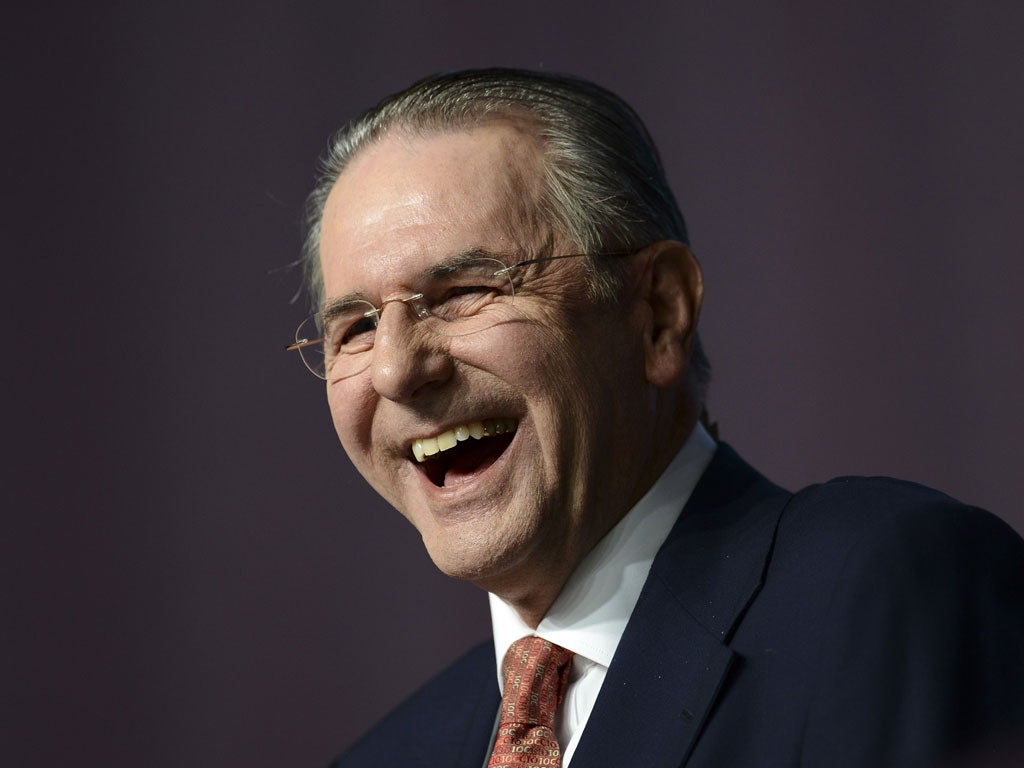

Jacques Rogge: The quiet Olympian

The International Olympic Committee is rarely far from controversy. How is its chief so good at rising above it? By Brian Viner

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With the long countdown to London 2012 finally over, the Belgian president of the International Olympic Committee, Jacques Rogge, might now be forgiven for starting a countdown all of his own – to the end of his tenure next year. It is not as though the urbane Rogge has ever given the slightest impression of not enjoying his job, but all the same, he must sometimes wonder whether, at the age of 70, he needs the aggravation.

Already this week, the former Olympic yachtsman has had to navigate some choppy waters. There was the unfortunate business with the North Korean women's football team, who walked off the pitch at Hampden Park on Wednesday after the South Korean flag had been shown on the stadium's giant screen. Rogge apologised for that "simple human mistake" but not for the IOC's refusal to arrange a minute's silence, during last night's opening ceremony, to mark the forthcoming 40th anniversary of the Munich massacre.

The opening ceremony, he suggested, was not the occasion to pay respect to the 11 Israeli athletes murdered by Black September terrorists during the 1972 Games. Instead, he said, there would be an IOC delegation at the military airport at Fürstenfeldbruck, where the killings took place, on the exact anniversary of 5 September.

It might well be that Rogge was right to rule out a minute's silence, on the basis that the opening ceremony "is an atmosphere that is not fit to remember such a tragic incident", but that has not stopped accusations – primarily in Israel and the United States, but also Germany – of shameless kowtowing to Arab sensibilities. As if that were not enough criticism to be getting on with, Rogge has also been lampooned by the British media for declaring himself and his IOC colleagues, in defence of their five-star, chauffeur-driven, police-escorted existence during the Games, to be "working class".

In fairness, it is not as though the London Hilton, where Rogge and other IOC grandees are staying, is exactly the plushest hotel in the capital. Moreover, he surely had a point, on being asked why they weren't staying somewhere humbler, when he countered that a three-star hotel would lack the required conference facilities, translators and so on. In the end, the question perhaps tells us more about ourselves than Rogge's answer does about him. Why shouldn't an important man stay in a smart hotel? As for the "working class" comment, the IOC's British director of communications, Mark Adams, probably nailed it when he said that the president, who speaks excellent English but does not count it among the five languages in which he is fluent, "didn't mean working class as in hammer and sickle. He just meant he works very hard".

Unarguably, he does. When I interviewed Rogge at the handsome IOC headquarters in Lausanne seven years ago, I got to see his schedule, and it would have seemed punishing to a man half his age. But never mind the volume of what he does, what about the substance?

As the eighth president of the IOC, Rogge, by general consent, has discharged his duties competently and sometimes brilliantly, but always quietly, without fanfare. It's a fair bet that, while he might defend his police escort during these Games, he does not actually enjoy it. Moreover, it is surely revealing that he has retained a degree of anonymity almost paradoxical in such a high-profile role. How many of today's Olympic spectators could name the IOC president? Less than half, probably. And, the acid test: how often is he cited in the perennially silly but irresistible challenge to name five famous Belgians? Never before Eddy Merckx and Hercule Poirot, anyway.

None of this means by definition that he is doing a good job, but all the same, it is instructive to compare him with his counterpart in football, the gaffe-prone and self-important Fifa chief, Sepp Blatter. Rogge lacks pomposity and rarely puts his foot in it, which makes him unusual indeed among leading sports bureaucrats.

On the other hand, and notwithstanding this week's travails, he has not been massively challenged during his 11 years in office, which is surprising, given that he took over from Juan Antonio Samaranch only two months before 9/11. "I have been blessed with a far more tranquil presidency than many," he told me in 2005, and the subsequent seven years have remained relatively tranquil. "My compatriot, [Henri de] Baillet-Latour, had to deal with the 1936 Berlin Games," he added. "Avery Brundage had to face the Munich massacre. Lord Killanin had to face the boycotts of 1976 and 1980, Samaranch had the 1984 boycott, the Ben Johnson affair, the Salt Lake City turmoil ..."

Samaranch, the IOC's hugely influential, long-serving, and on occasion self-serving, seventh president, had been a professional diplomat. Indeed, it was his time as Spain's ambassador to Moscow that won him the support of the Soviet bloc countries and, in 1980, clinched his election to the job he so coveted. He used the darker arts of diplomacy throughout his 21 years in office, plotting and manipulating in smoke-filled rooms, but that has never been Rogge's way. Just as Samaranch drew on his professional background, so Rogge has drawn on his.

"From surgery I have got a much-needed sense of humility, of the uncertainty of life, of the frailty of every ambition," he told me in our interview. "And surgery teaches you to be systematic. It is like being a pilot, a profession full of checklists. Also, you have to be able to take tough decisions. For example, if you do not amputate, the patient will die."

But what, I asked him, about the emotional dimension of sport? Could he really tackle the problems of sport with the same clinical detachment he had required in the operating theatre? "I am also a great lover of modern art," he replied gnomically, gesturing towards a picture on the wall behind him. "This is a Mondrian. If it were original it would be worth $60m, but it is a very good copy. Look at it. It is just a composition of planes and colours, yet it moves me. Every time I am in London, I visit the Tate Modern and the Saatchi. And in Moscow, The Black Square by Malevich, painted in 1912, intrigues me greatly. It is enigmatic, like the smile of the Mona Lisa. Last time I stood in front of it for 20 minutes. In sport there are events that have the same effect on me, like when Steve Redgrave won his fifth gold medal and Matthew Pinsent won his fourth. I went merely as a spectator, and in both cases I felt a great emotion."

It would doubtless be doing Rogge a disservice to suggest that the opportunity to stand in front of Malevich's The Black Square was in his thoughts when, in 1980, as head of Belgium's Olympic delegation (and having competed in the Games of 1968, 1972 and 1976), he defied his government's wishes, and overcame the denial of public funding, by leading a team to Moscow. The Americans had called for a boycott of the Moscow Olympics and, as a Nato ally, Belgium was inclined to oblige, but with resolve and no little courage, Rogge insisted his country's athletes should not become political pawns.

It was one of the defining episodes of his life, and among the reasons he was awarded the IOC presidency 20 years later. Another was his nationality. The leadership of major world organisations rarely falls to people from major world powers, lest they be even perceived to have undue influence. "It is better to come from small, insignificant countries like mine," Rogge has said. "Being humble is sometimes a help."

There will be those who ridicule the idea that there is anything humble about Rogge himself, just as they ridiculed his claim to be working class. Certainly, he comes from an affluent family, and has been ennobled by King Albert II, making him and his wife, Anne, a count and countess. And yet if anything has defined his presidency, it is his empathy for small players on the world stage. His devout wish is to reduce the cost and complexity of staging the Games, so that developing countries might host them in the future. London today, Angola or Bangladesh or Cambodia tomorrow? It would be a truly worthwhile legacy.

A life in brief

Born: 2 May 1942, Ghent, Belgium.

Family: His father was a track athlete and rower; his grandfather, a cyclist. Married to Anne, with two children; his son, Philippe, is delegation leader of the Belgian Olympic Committee.

Education: Studied sports medicine at University of Ghent, graduating as a doctor of medicine. Fluent in five languages including French and Spanish.

Career: Former orthopaedic surgeon, he competed at 1968, 1972 and 1976 Olympics as a yachtsman and played rugby for Belgium. President of Belgian and European Olympic committees before becoming IOC president in 2001.

He says: "The quest for medals is not everything, but it is important."

They say: "He's a leader, knows what he wants, but is a modest person." Sergey Bubka, retired pole-vaulter

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments