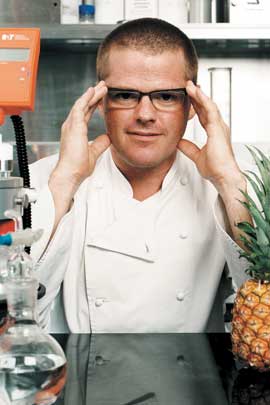

Heston Blumenthal: The taste maker

Heston Blumenthal is turning the culinary world on its head, challenging everything we take for granted. The professor of the pantry invites Nick Duerden on a gastronomic odyssey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Heston Blumenthal, a modern-day Willy Wonka, smiles broadly. "The nerve centre," he says. Blumenthal has been our most futuristic chef for some time now, his restaurant - a thunderbolt of tomorrow in the sleepy village of Bray - in existence for a full decade. Recently voted the best in the world, its superchef was also awarded his third Michelin star last year for creations that have as much to do with science as they do food. "I certainly don't consider myself a scientist," he says, "but the academic world insists that what I'm doing here is practical physics. The way I see it, I'm just having fun with experiments."

This unassuming 38-year-old makes for an altogether unusual kitchen whizz. Largely self-taught and, today at least, polite to his staff in a manner that would presumably shock Gordon Ramsay, his puppyish enthusiasm is powered by an insatiable craving to take food on to another level altogether. This isn't, he stresses, merely for his own amusement, but to enlighten the nation's repressed tastebuds. Not content with developing the most scientifically accurate way of cooking meat - he slow-roasts it for a great many hours in pursuit of ultimate tenderness - and having tantalised taste buds with such delicacies as mustard ice-cream, his next step is an ambitious one.

"I want to go into the realms of neuro-linguistic programming and cognitive research," he says, eyes wide. "It's not as complicated as it sounds, I promise you, but I'm increasingly fascinated by the psychological side of food."

In order to explain this to me (someone whose GCSE physics exam paper was returned with the words "This is an insult to the examiner") he breaks his theories down to their most basic form.

"OK, why do you think a bottle of Muscadet will always taste better when drunk on holiday by the Loire than in your front room?" he asks. "Context, that's why. What we are trying to do is contextualise the whole eating experience as much as possible, making it a feast for all the senses, and to play with the diner's perceptions and expectations of what they are about to eat."

Thrillingly, he offers to demonstrate, and offers me ice cream that changes flavour, as I eat it, from cinnamon to vanilla. This miracle happens because he squirts the aroma of either ingredient into my nostrils between each mouthful, using squeezy plastic bottles, the vanilla ultimately saturating the cinnamon and replacing it. It's cute, this, and quite a hey-presto moment, but before I can fully digest it, he brings me a cup of tea which prompts an exquisite confusion on the tongue by being simultaneously hot and cold. "Good, eh?" By now, he is beaming.

His most exciting new creation is also the most theatrical. Blumenthal has been celebrated for his smoked-bacon-and-egg ice cream. But he has also received considerable derision, not least from one New York chef (whom he refuses to name). After one critic recently hailed him a genius, the American responded: "If I made ice cream from my own vomit, would I be called a genius too?" Undaunted by such scorn - "the bloke is old-school" - he has given this most infamous of puddings a delightful twist. It now comes presented at the table in a frying pan, into which liquid nitrogen is poured. Amid plumes of dry ice, it is briskly whisked until, voila, it has the texture and look of scrambled eggs. Blumenthal offers me a spoon. Cold and crisp, it brings to my mouth the most intense bacon flavour, followed by an explosion of the creamiest egg yolk my tongue has ever known. I have to sit down afterwards.

Fun, but all this is just a gimmick, right? Apparently not. Blumenthal is currently in discussions to create a new branch of food science to be taught in schools, and he is also working on a book which, he claims, will simplify his concoctions for us to recreate at home.

"Don't think of it as molecular gastronomy," he insists, referring to the buzz phrase attached to the Fat Duck. "Think of it as cooking with imagination. If anything, I want to dismantle barriers, because great food really can enrich your life." He talks on, but I'm no longer listening. My fingers are in the frying pan now, working up remnants of scrambled eggs, all my inhibitions lost.

To request a hard copy of Fuelled please email ismailbox@independent.co.uk with all your postal details

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments