Hans Blix: From the hell of Iraq, hope for an era of peace

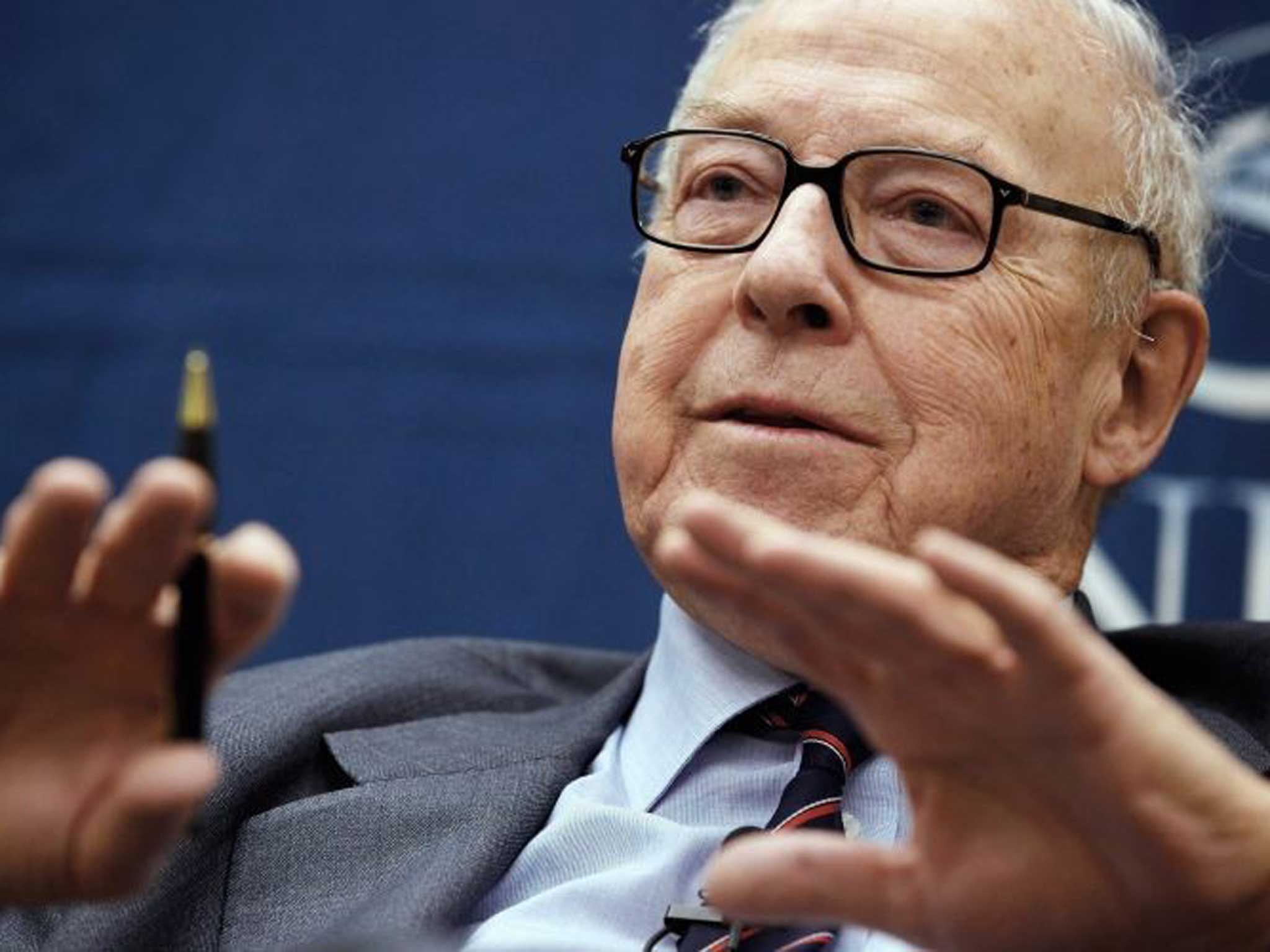

The UN weapons inspector who failed to prevent the invasion 11 years ago, believes it is the last such conflict, as nations learn to co-operate. Margareta Pagano meets Hans Blix

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The man at the eye of the storm over whether Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction believes the Iraq war could prove to be the last big conflict between nation states. What's more Hans Blix is also optimistic that, after the Iraqi devastation, there could be emerging a more peaceful balance of power in the world.

The former United Nations weapons inspector, who weeps still over the United States invasion, calls what's happening in the Middle East today a "reset" as the five permanent members of the UN Security Council– the US, Russia, China, Britain and France – the warlords (or P5) as he describes them, are finally pulling together. "What I see in Syria, with the Russians and the US working together, and China not objecting, and now in Iran, is a mini reset in the global order. The fact that the P5 demanded Iran should stop enriching uranium to 20 per cent [the purity level at which it could be converted to weapons grade] was a small step but an interesting sign."

"You don't have just one power deciding but a junta – it's collective leadership that has demanded this restriction. These are embryonic changes but they are important ones. Today, we see the UN working for the destruction of chemical weapons in Syria. Tomorrow I hope we may see them in IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency] inspections of nuclear installations in Iran – rather than US bombings."

For Dr Blix, the game-changer was public horror over the Iraq war and its aftermath, in which over a million people are estimated to have been killed. "After the unsuccessful war in Iraq it's my belief there will be fewer unilateral military interventions and fewer wars between states – the 'big thugs' – and we should expect greater global détente and more international cooperation. This is my hypothesis and my hope."

But isn't this what people said after the First World War – the war to end all wars? "Some will think I am as naïve as those who had similar views in 1918. But it is no longer romantic thinking to suggest that risk of wars between states – I am not talking about civil war or terrorism – is decreasing." His reasons are these: with the end of colonialism, armed land-grabbing is over, most borders between states are settled and after the end of the Cold War, religion and ideology are no longer grounds for wars between states. At the same time, institutions such as the UN Security Council, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organisation, G8 and G20, and international courts are helping resolve controversies, and interdependence has increased exponentially.

"Remember Dag Hammarskjöld? Well, he used to say the UN was not created to bring us to heaven but to avoid going to hell."

By far the biggest catalyst for change has been President Barack Obama. "You have to admire Obama, and John Kerry; they are doing a great job, and the agreement with Russia over Syria on chemical weapons was excellent, as was the decision not to intervene in Syria. Obama has a trump card – war fatigue in the US. People do not want to send their children to war." He praises Obama for resisting both US militarism and Aipac (American Israel Public Affairs Committee), so preventing another armed conflict in the Middle East. "With a hawkish Congress and with Israel and Saudi Arabia as close traditional allies this is not easy but it's working. Shale gas has also given Obama a great freedom to be tougher in the region. The US and Russia should put more pressure on Iran, Saudi Arabia and Qatar to stop them giving money to rebel groups."

The decline of the big thugs going to war is something the former Swedish foreign minister and international lawyer turned nuclear expert has been brooding upon for months and is working on for a book. I caught up with him at his flat overlooking central Stockholm. It's a lovely space to brood in, covered with bold paintings and gorgeous Iranian and Caucasian rugs bought on his travels while heading the IAEA in Vienna.

He will be 86 in June, yet still scours the world's press for at least three hours a day, chairs the international advisory board of the Abu Dhabi nuclear programme and lectures on how we should be working for nuclear disarmament. What appalls him most is that $1.7bn (£1bn) a year is being spent on arms, 40 per cent of which is from the US taxpayer.

"Is this prudence or over-insurance? Why does the US need 12 new submarines or missiles stationed in Romania if Russia is not a threat? Why do oil-rich Middle East states spend the money coming out of the ground from oil on the latest weaponry that will be obsolete in 10 years? There are 20,000 nuclear weapons ready to blow up. Nato has 200 of them, yet everyone knows they are useless. We must double our ambitions to stop war and stop the weapons build-up which is a bloody waste of the world's resources."

So why isn't there a stronger peace movement today? "Public opinion in the vocal West no longer feels any acute agony over war with Russia. And governments cannot, thank God, increase their military budgets." Who better than him to lead one? "No, I'm not a street man," he chuckles: "I think and write and brood – and look after my grandchildren."

He's handy in the kitchen too – he has made fruitcake to go with the coffee. Dr Blix supports his theory that we are entering fresh terrain by studying the past: "How does a rule of law arise? If you look back to medieval times, you can see how chieftains were asserting themselves and attained central control. In time they submitted to constitutions and in the end we arrived at general suffrage and democracy.

"Majority decisions are a fundamental need – yet the minority must know that the majority will not chop off their head – that is the fear we see in countries like Iraq."

By his analysis, the international community is emerging from that medieval stage; the Second World War established the P5 junta – but the old warlords proved unable to rule together. "Now we are seeing signs that the thugs are growing up and taking collective leadership for security – which is why the P5's decision to rein back Iran's enrichment is so crucial."

It's 11 years next month since his UN team was pulled out of Iraq days before the US invasion. Dr Blix has no regrets about his role. To many he is the only player to emerge with integrity, having told the Security Council many times he had found no weapons of mass destruction. Yet some argue that if he had screamed louder that a deadly arsenal didn't exist, he could have removed the legal and political reasons for war.

He met one of them, Dr Jaffar Dhia Jaffar, the Iraqi nuclear scientist, a few months ago in Dubai. "Dr Jaffar said: 'You could have stopped the war. You should have stood up and said there were no weapons'." Was he shocked? "No, it was a civil meeting. I explained that I could not prove a negative, and we would have lost all credibility if we had claimed the evidence was conclusive. We were international civil servants reporting facts, not political advisers.

"But I do weep still over the result of the mad rush by Bush and Blair to go to war. Tragically, the US and UK trusted their own faulty intelligence more than the inspection reports we gave." He suspects that the Bush administration, which he says didn't give a "damn" about the UN, counted on war from the outset, and that a March deadline had been picked because of the extreme heat.

What next for the Middle East? "Well, I have a radical solution for détente, which is a nuclear-free zone – it was on the agenda two years ago but the US pulled out. A zone needs to be negotiated by the countries in the region – not imposed from outside – and could involve Israel giving up its nuclear weapons in return for Iran giving up all fuel-cycle installations." This sounds like pie in the sky, but he sees no reason why such a zone could not be negotiated in the future as it would benefit all.

There's one big caveat to his optimism – simmering US-Sino relations. "The US must be careful of humiliating China, also India and even Brazil. Humiliation is what provokes white fury and revenge. If you continue my junta thesis, you must have all the boys and girls – especially the big ones – at the table. They must not be slighted but should be pulled in to world organisations like the IMF to play their proper roles.

"Countries are now so interdependent that they cannot afford armed conflict but must listen to each other and cooperate." They should heed the Cold War prophesy of the Danish poet, Piet Hein, who wrote: "The noble art of losing face/ may one day save the human race."

Curriculum vitae

1928 Born in Uppsala, Sweden to mother Hertha Wiberg and father Gunnar Blix, a professor of medical biochemistry at Uppsala university. Attends Uppsala University and then studies International Law at Columbia University, in New York.

1959 Awarded PhD from Trinity Hall, University of Cambridge, and becomes Associate Professor of International Law at Stockholm University.

1962 Is part of the Swedish delegation at the Disarmament Conference in Geneva. Marries Eva Kettis, with whom he has two sons.

1978 Appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs in Sweden's Liberal government, a role he holds for only one year.

1981 Becomes Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, and oversees the organisation's response to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986.

2000 Named head of the United Nations' Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission, following 17 years leading the IAEA.

2002 Asked by UN Secretary General Kofi Annan to lead the UN Weapons Inspection Commission in Iraq.

2003 His report to the UN Security Council advises against invasion after his team finds no evidence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

2004 Publishes his first book Disarming Iraq. Also receives France's highest award, the Commander of the Legion of Honour.

2010 Tells the UK's Chilcot inquiry that the Iraq war was illegal.

2013 Advocated for western diplomacy in the Middle East as civil war in Syria escalates and Iran elects a new President.

Zachary Boren

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments