Graphic novelist Raymond Briggs appeals to the British public for help with his next project

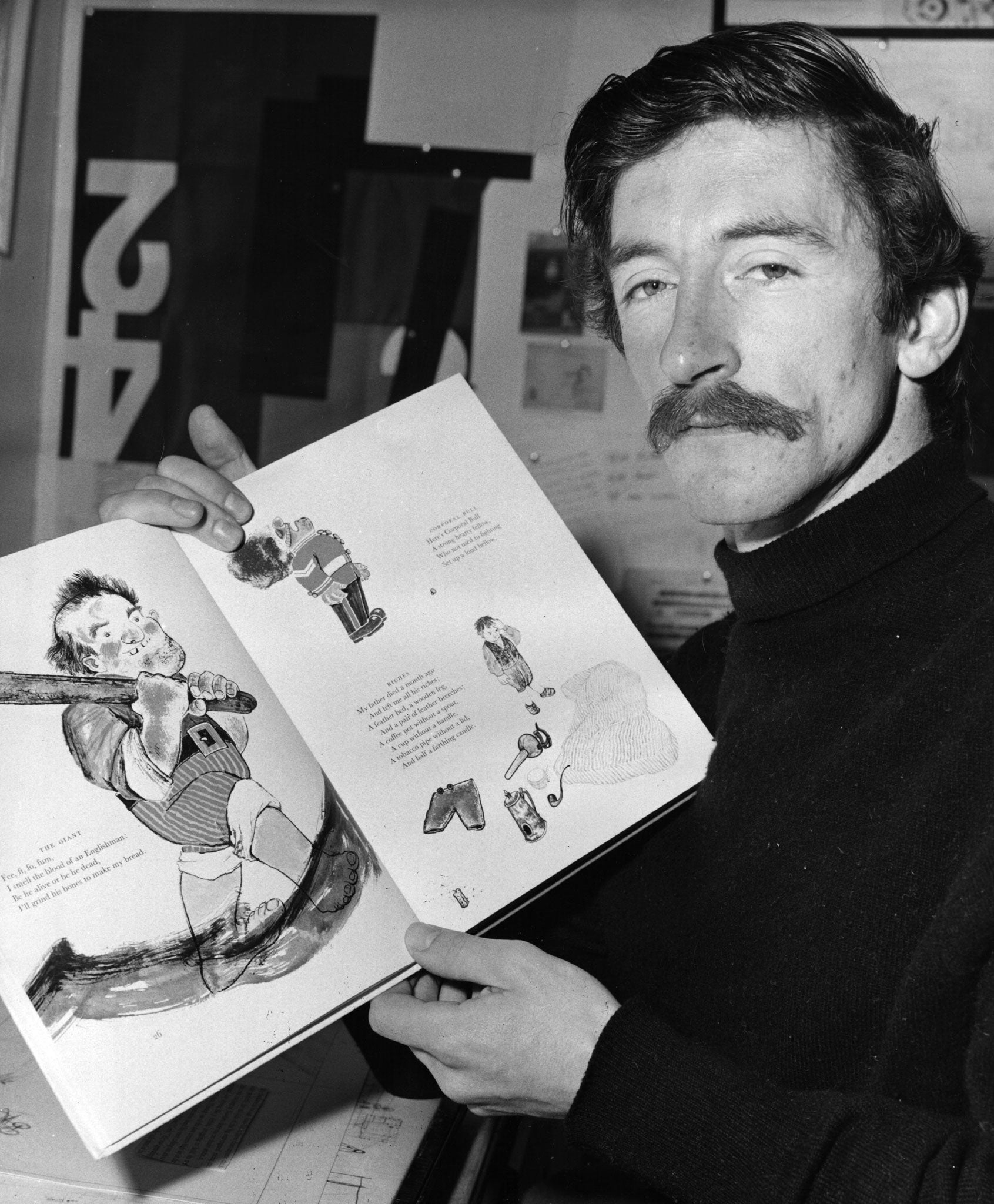

Briggs is a world-class grumbler and the solo genius behind The Snowman and Fungus the Bogeyman. John Walsh meets him at his home in Plumpton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It takes five minutes in Raymond Briggs's company to realise who he reminds you of. As he moves at a fast 80-year-old shuffle around his partner Liz's house near Plumpton Racecourse, his conversation is a kind of stream-of-grumble. There's a draught from the door; his mouth is too dry to let him speak; there's a script of the new Fungus the Bogeyman film he hasn't had time to read. He grumbles about technology ("I hardly touch my iPad thing because it gets me in a temper. I need it to keep in touch through incoming mail, but that's all I use it for") and television shows ("I looked up Foyle's War in the Radio Times and it was on for two hours, I mean two solid hours. I couldn't sit through that, however much I like Michael Kitchen") and British politics ("Nigel Farage is the only person I like because he's slightly amusing. The others, these dark-haired blokes of about 40, I can hardly tell the difference between them") and the trials of age ("When you get older everything takes so bloody long, getting the food, clearing up, washing up, getting the bedroom ready, having a bath...").

He's a world-class grumbler and, despite his lack of white beard and straining waistband, you can't help thinking how he resembles his 1973 creation, Father Christmas. Briggs imagined Santa Claus as a British working man, an ordinary bloke weighed down by the drudgery of reindeer and gifts. He isn't jolly; he grumbles about the cold, the blooming rain, the rooftops, the flipping strain of delivering presents all night, before he can go back to his fire, his cat, his cosy chair and glass of Scotch.

One could draw a further parallel with Briggs, sitting at his drawing board with pencils and gouache, his own toy factory, working away for the 18 months it takes him to complete each strip cartoon/graphic novel, an anchorite of illustration who sends his works out to children all over the world. But Mr Briggs is wary of praise or gush. He doesn't mind meeting his readers, "if it's brief". How does he enjoy it when people come up and start singing the Snowman song, "I'm Walking in the Air"? "Aaaarrrggh!" – he shuts his eyes in theatrical pain – "I want to give them a kick up the arse. There was a list of the '10 Most Hated Tunes' in the paper a couple of years ago. 'Walking in the Air' was No 7. I sent a cutting to Howard Blake, the composer, as a joke."

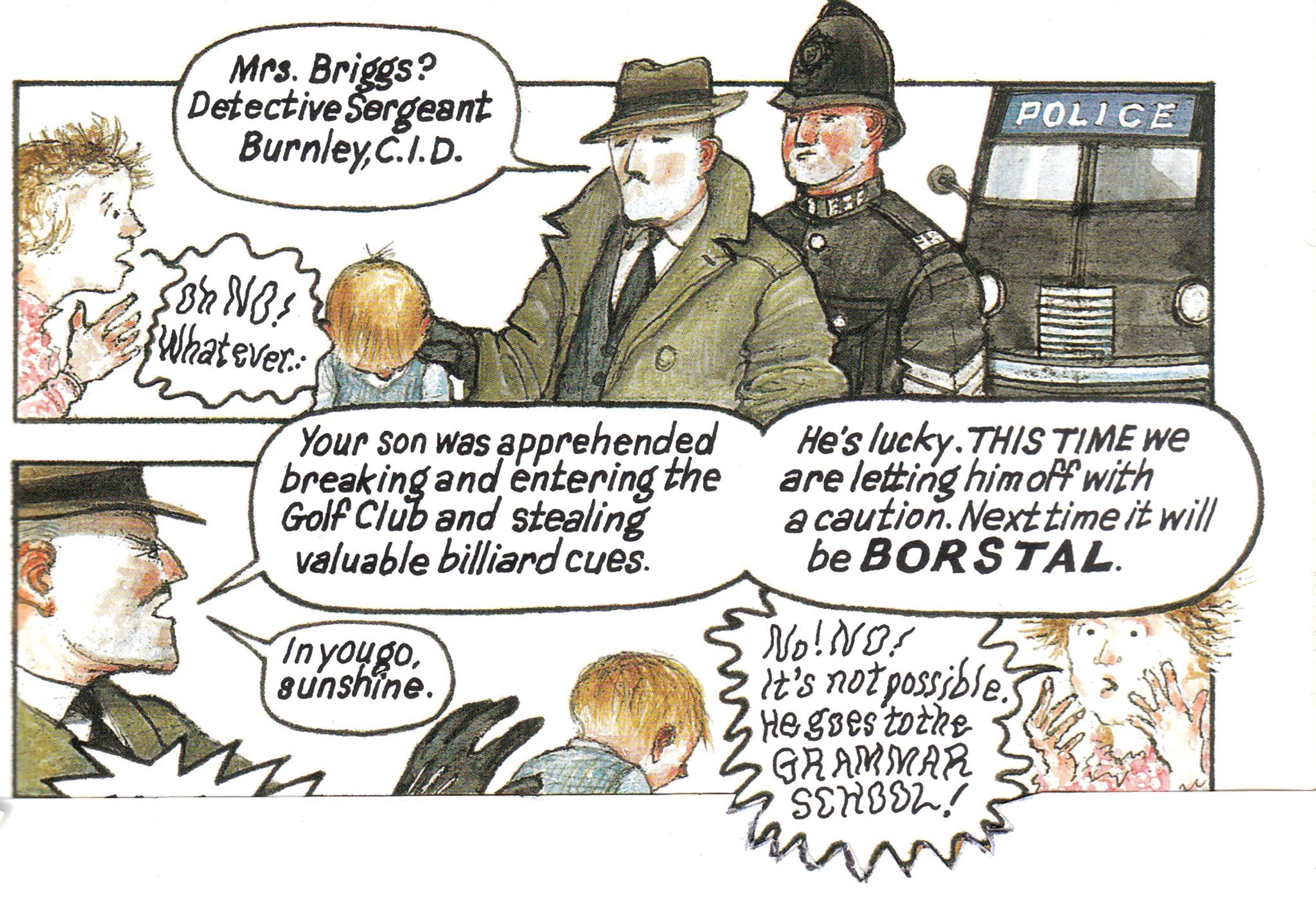

He has, in the past, been doubtful about adaptations of his work. He didn't care for the original animation of The Snowman by Dianne Jackson. He thought the way it dragged in a visit to Santa Claus (not in the original story) was "a bit corny and twee". He was against the idea of a sequel, The Snowman and the Snowdog, for decades. But the world will not leave him alone. A film of Ethel & Ernest, his graphic novel about his parents' lives (and a social history of the 20th century), has been in production for a while, with the voices of Jim Broadbent and Brenda Blethyn. And Andy Serkis's company has just agreed to film Fungus in motion-capture, with Timothy Spall supplying the Fungoid rasp.

Another venture has brought him dangerously close to pleasure. Mr Briggs has discovered crowd-funding. The people at Unbound have asked members of the public to pledge money to publish a collection of Briggs's columns from The Oldie, and are more than halfway to the amount required. "I think it's marvellous," said Briggs with uncharacteristic glee. "A terrific idea. I'd never heard of it until recently. It made me think, 'Who the hell's going to want this book, for God's sake?' But people responded, and it's very rewarding."

He was asked to write a column by Naim Attallah, who funded The Oldie in its early days. He was told he could write about anything that caught his attention, and his columns have tackled some very odd subjects. In one, he reveals that he's constantly badgered by Japanese fans who seek him out at his Sussex retreat – and, to kill two birds with one stone, take him along to visit the bridge immortalised in the Pooh Sticks chapter of Winnie-the-Pooh. "They come to see me, for interviews, and they know Pooh Sticks Bridge is half an hour's drive away. There's nothing to see – a tiny little stream and an ordinary little wooden bridge, which isn't even the original one. But they stand there looking at it, and taking photographs. It's ridiculous."

In another column, he admits his bafflement, as a child, about sex. He recalls the extraordinary detail that, at his primary school, a little girl told her class that she'd found traces of her father's sperm on a lavatory seat, had put it inside her – and later given birth to "half a baby". Briggs's eyes widen with astonishment. "What a thing for a child to... she couldn't have been more than nine. It's supposed to be a pre-sexual age." Was this where his fascination with human grot – the exudations of Fungus the Bogeyman and his world of bodily fluids, zits, corns, snot, mucus and slime – got started? "No," said Briggs firmly. "Everyone's got that in their life. Everyone has to deal with disgusting things, being sick, going to the lavatory, having diarrhoea..."

How did he respond, as a professional illustrator, to the news from Paris that depicting a religious figure as human could result in the death of 10 artists? "It's a world that's right outside me. I'm not religious at all. I suppose there was a time when you couldn't depict Jesus Christ. But it's far beyond my comprehension, I'm afraid." Does he think the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo were foolish to court trouble? "No, that's their job. But they must have been aware of the consequences and known that something serious could happen – not getting killed, perhaps, but getting beaten up or something. If you're treading on sacred ground, you have to be damn careful. It's a terribly dangerous field." Does he think we're generally free to say what we like these days? "In British society, I think we're pretty free. You can say things about the Queen, the Pope, Catholics and the Church of England without anyone going beserk. But with this Allah business, you're on different ground altogether."

Briggs is amused by the circularity of political correctness. "Decades ago, when my mum was ill, my dad talked about getting a 'cripple chair'. She said, 'DON'T use that word, it's a wheelchair'. The word 'cripple' was used then, but you wouldn't dream of using it now."

I tell him that the Sun newspaper, that morning, in a story about a TV soap star being ejected from the Big Brother house, called the word Negro "the N-word". Is it unsayable? "I remember Alistair Cooke saying that, when he started Letter from America, he'd never refer to a person as 'black'. It would have been considered terribly rude. Thirty years later, 'black' is fine, and 'Negro' is rude. Things that are outrageous in one decade are perfectly OK in the next. We'll probably all be saying, 'Look at those Negro cripples' in another 10 years."

Briggs was born in 1934 in Wimbledon Park. As readers of Ethel & Ernest know, his father was a milkman, his mother a one-time lady's maid in Belgravia. His father had to get up at 5am and go out in all weathers (like Father Christmas – and Ernest turns up in the book, saying to him "Still at it mate?").

During the war, Raymond was evacuated to the countryside; his letters home featured little pictures in the margins. "When I was 10, I wanted to be a reporter, then a cartoonist. I went to Wimbledon School of Art for an interview at 15, and the principal asked me, 'Why do you want to come to my art school?'. I said, 'Well sir, I want to learn how to draw, in order to become a cartoonist'. He went purple in the face. He said, 'You WHAT? My GOD, boy, is that ALL you want to do?'."

He went, though, and to the Central School of Art and the Slade, where Paula Rego was among his contemporaries. Why didn't he pursue painting? "I didn't feel I was a proper painter," he says. "I could do landscapes, and people have praised what I've done. But I don't like oil paint much – I find it difficult, messy, wet and sticky – and if you're going to be a painter, you've got to love oils."

Instead, he became an illustrator of fairy tales for Oxford University Press. He displays a breezy disdain for classic fairy-tale artists ("Arthur Rackham? I've never liked him. His stuff is too self-conscious, too design-ey") and claims much more distinguished figures as influences: "I always liked the northern peasant painters, like Rembrandt and Breughel, rather than Italian southern painters, with their great fat virgins and babies."

His golden years in the 1970s, a decade which produced Father Christmas, Fungus the Bogeyman and The Snowman, followed a triple tragedy: his parents both died in 1971 and his first wife, Jean, died in 1973. Were the books a response to bereavement? "Jean was in hospital when I was doing Father Christmas," says Briggs. "I used to take the illustrations into hospital to show her every day." So was it therapeutic to...? "I don't think about that," he says shortly. "I just got on with it."

For the past seven years he's been working on a new project, "a great fat book about old age and death. The title is Time for Lights Out. It's a compendium of drawings and poems and reflections." He shows me two big black folders containing 150 pages of cartoons, illustrations, bits of text. "It could be jolly good," he says gloomily, "but it's been completely buggered by Liz's illness." (She has Alzheimer's.)

Did he say poems? "Yes. I didn't even know they were poems. Michael Morpurgo was doing a book about the First World War and asked me if I'd got anything. I'd written a piece about the number of aunts that were around in my youth. I thought that's just the way the world was, all these elderly single ladies. When I grew up, I realised they were only in their forties and, after the war killed nearly a million men, there were a million women without a bloke. Michael raved about it. He said it was a poem, and he should know. So that was a great lift-up for me."

Before we part, I ask him about one entry in the book: a list of names with dates beside them. "It's the dates, and times of death, of cartoonists and illustrators," he says. He shows me another list in the kitchen, of the current state of health of living cartoonists and illustrators: who has dementia, who's in a home, who's in a "cripple chair". Why does he keep a record? "I don't like being taken by surprise," he says simply, "by people telling me one of them's died."

It's rather heartening to imagine the brilliant Mr Briggs grumbling at a visit from the Grim Reaper, and telling him he's far too early, he's letting in a draught and he's come to the wrong address.

To crowdfund Raymond Briggs's 'Notes from the Sofa', visit unbound.co.uk/books/notes-from-the-sofa

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments