Gavin Maxwell's bitter legacy: Was the otter man the wildlife champion he appeared to be?

The aristocrat wrote a best-selling memoir about the life he lived in Sandaig with his pet otters, and his eccentric devotion to them inspired a generation. But our greatest living nature writer believes his legacy has been quite toxic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As I walk down a forest path on the coast of north-west Scotland, my heart is beating fast. It's not so much the physical effort – the way is not steep – but my sense of expectation that is causing this effect. What I am about to see is a near-mythical place, one I have read so much about and visited so often in my dreams, but never in reality.

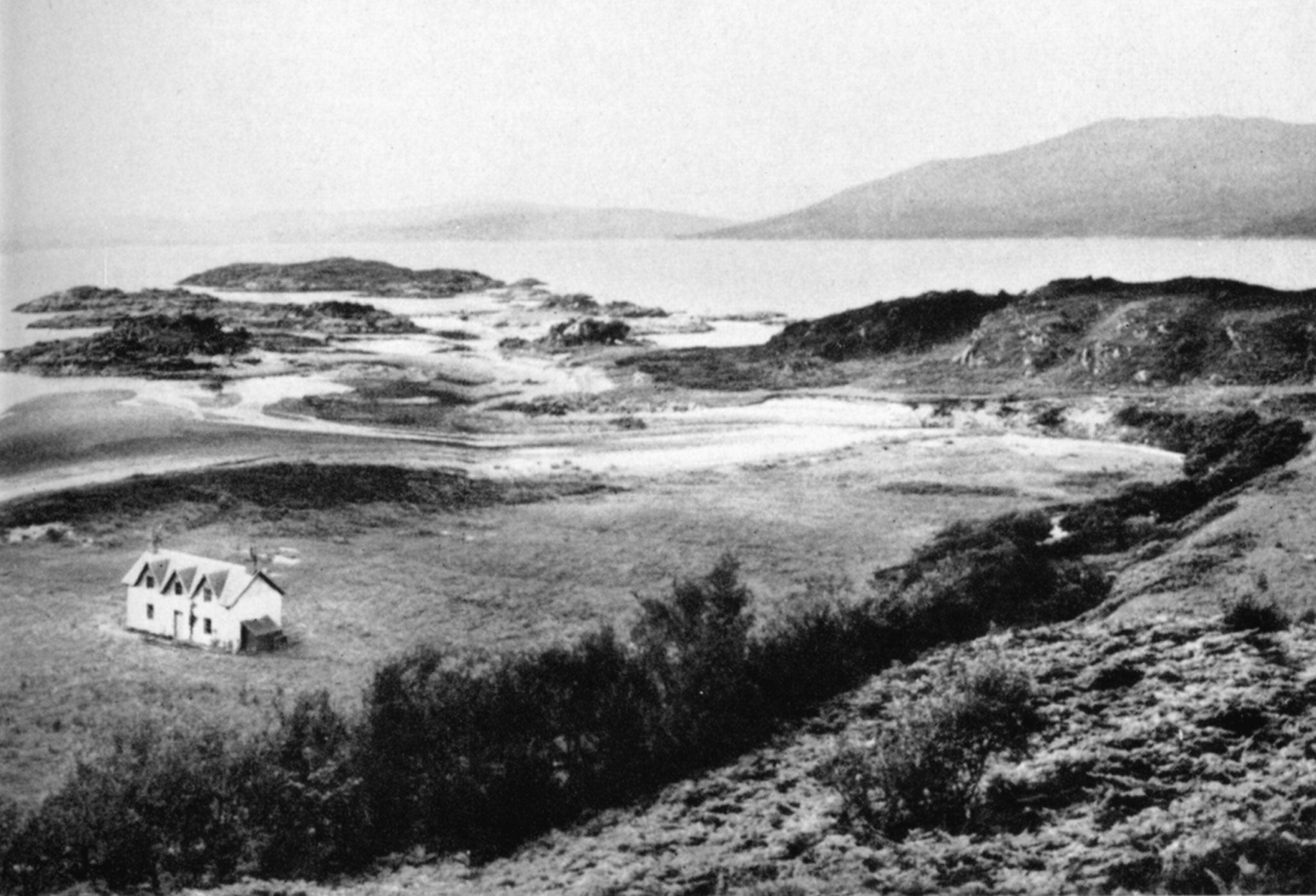

Soon the view opens up and what appears in front of me is a little bay of sand and sea encircled by trees and a stream, a sublime composition of natural elements that has become famous the world over as the setting for Ring of Bright Water, Gavin Maxwell's best-selling memoir about the life he lived here with his pet otters. The book was published in 1960 and, like millions of other readers, I feel it has shaped my view of nature. Now I have come to Sandaig, a wild and isolated spot overlooking the Sound of Sleat to Skye, to see the site of this saga for myself.

It is a timely moment to reflect on Maxwell's legacy. This Tuesday marks the centenary of his birth, and the occasion seems ripe to re-examine the sometimes-controversial reputation of both the man and his most celebrated book.

Read in isolation, Ring of Bright Water paints a poetic and moving picture of a period in Maxwell's life which he later came to regard as a lost paradise. The story recounts how in 1948, aged 34, he had been offered the use of an empty lighthouse-keeper's cottage at Sandaig as a bolthole to which he could escape for holidays with his springer spaniel, Jonnie. His evocative descriptions of life in his Highland home are now part of the literary canon, but it was the magical story of the relationships he formed with three otters which made his bewitching back-to-nature memoir a sensational bestseller.

Maxwell's otter odyssey began in 1956, when he set off on a journey to explore the marshes of southern Iraq with the explorer Wilfred Thesiger. There he adopted his first otter, a tiny cub he called Chahalla. Maxwell lavished this baby animal with all his affection and was desolate when it died just a few days later.

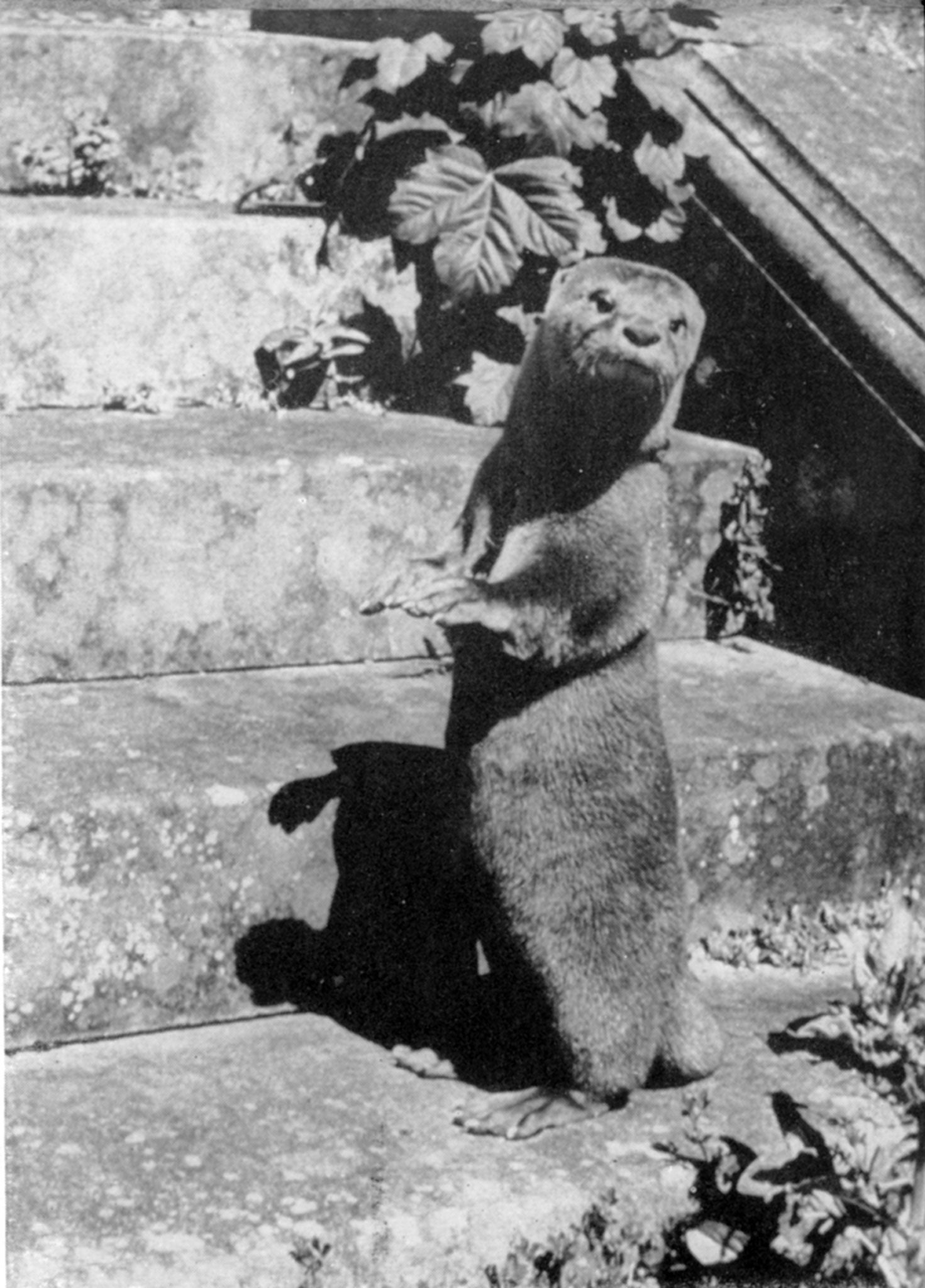

To console him, Thesiger found him another otter to take home, a squirming velvet ball "the colour of milk chocolate", which Maxwell christened Mijbil. After an eventful flight, Gavin arrived in England with his new pet and they began the year of happy adventures together in London and Scotland that form the heart of his classic book. "Into this bright, watery landscape Mij moved and took possession with a delight that communicated itself as clearly as any articulate speech could have done," he wrote. "The waterfall, the burn, the white beaches and the islands; his form became the familiar foreground to them all."

But Ring of Bright Water is not a children's story; rather it reads like a dark fairy tale, and the account of Mijbil's murder by a road-mender with a pickaxe on a lonely Scottish lane is one of the most heartbreaking moments of modern literature. Maxwell was away at the time, and had to piece together the story from village reports: "Mij had been on his way home when he had met Big Angus, and he had never been taught to fear or distrust any human being. I hope he was killed quickly, but I wish he had had one chance to use his teeth on his killer." The salvation that comes when fate brings Maxwell another otter, Edal, gives the book a narrative arc that even the most carefully constructed fiction would be hard pushed to match. It's both a tear-jerker and a heart-warmer, and the numerous photos and drawings of Maxwell's curious creatures only add to its seductive appeal.

Today the book is widely regarded as a literary masterpiece. But the deaths of the animals in Maxwell's care, and the way in which he coveted them as pets, is also at odds with our modern attitude to wild creatures. Richard Mabey, author of Food for Free and our greatest living nature writer, agrees that a darker view of Maxwell needs to be put on record. "I read the books [Ring of Bright Water and its two sequels] when I was quite young and I was captivated; he's a good descriptive writer, and the romantic idea of this immersion in a remote hideaway with his menagerie was compelling to me," he says.

"But since then I've got a very different view of him. The fact that he was, by literally all accounts, an extremely unpleasant man, I think is neither here nor there. It's more what I now feel about his writing about animals, and his treatment of animals. I feel that his legacy has really been quite toxic. He seems to me to be part of that period which was all about developing a relationship with wild animals that was appropriative; that the way to understand them was to domesticate them, imprison them, tame them and keep them as pets. And I think that because his writing is so seductive in its glitter, he helped to perpetuate that idea into the current era. So when I see the compulsion among a certain type of naturalist to hold wild animals, to have them in their grip – you see it all the time on TV – I'm uncomfortable about that. It's not the kind of relationship that we need, in our ecological maturity, to develop with wild creatures."

It's fair to say that Maxwell, who was a keen student of Freud, had himself questioned the reasons for his strong bond with animals, and had traced the origins back to his unusual childhood. The son of the heir to a Scottish baronetcy, he was born only three months before his father was killed in the opening offensives of the First World War. His mother, Lady Mary Percy, a daughter of the Duke of Northumberland, was distraught, and sought solace in the adoration of her baby son. Gavin shared his mother's bed until he was eight years old, and later recalled his separation from her to go to boarding school as one of the most shattering events of his life.

From this point on, Gavin saw himself as an outsider – the fatherless baby on a quest to find the warmth and security he had lost as a child. This feeling that he was somehow different lasted his whole life and manifested itself in various colourful ways. He was a fair, blue-eyed man of medium build who liked to wear a kilt and to keep his cigarettes in his sporran. Early on he developed a passion for fast cars (he once owned a Maserati racing car converted for road use) and was a first-rate shot and gun expert. He drank heavily (whisky), and was attracted to danger and adventure. His awareness of his homosexuality and his attempts to repress it only toughened him the more, making him determined to prove himself a man of action.

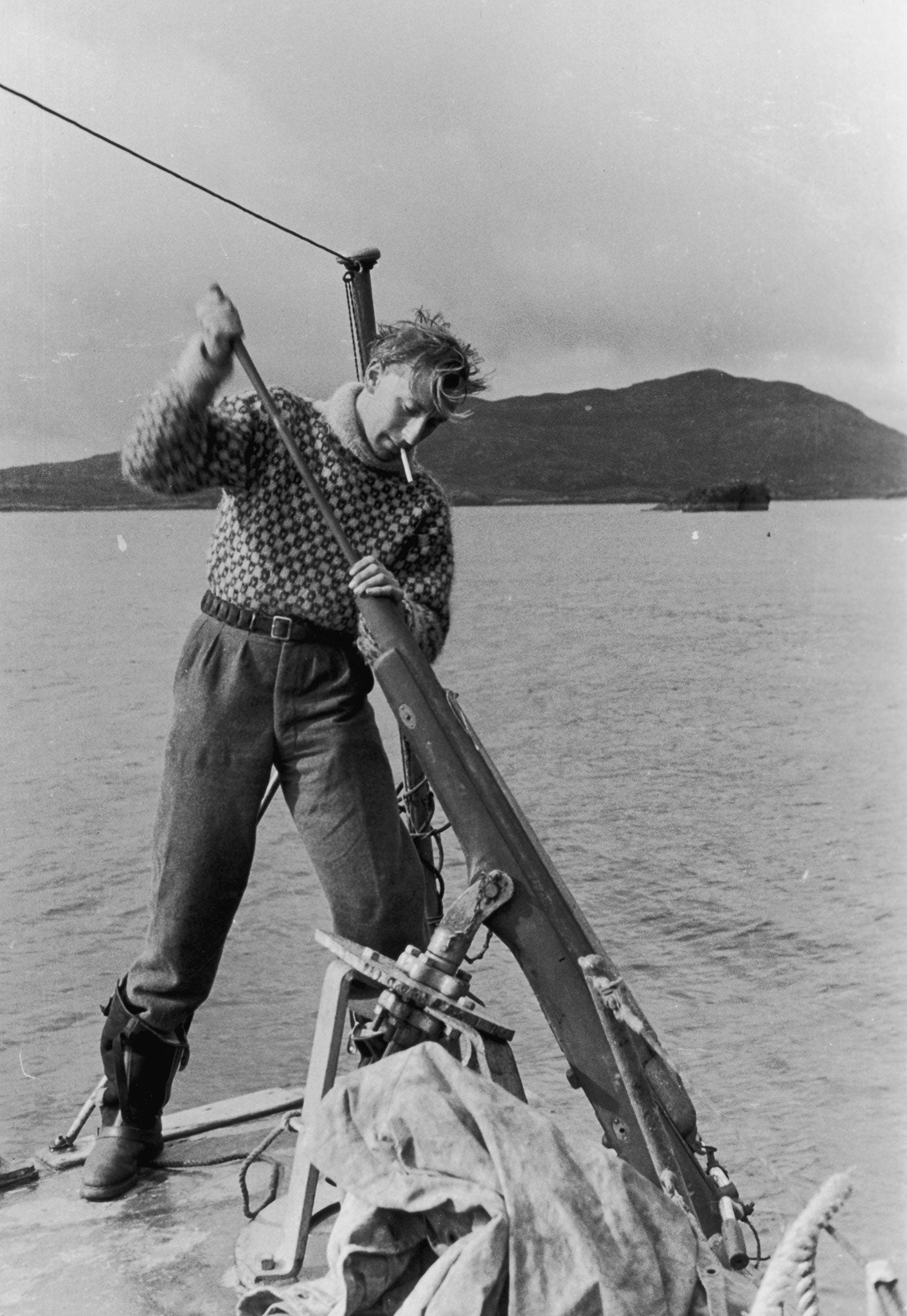

His chance came when war broke out in 1939. Maxwell joined the Scots Guards, but was soon seconded to the undercover Special Operations Executive in Scotland, where he trained resistance fighters in the use of firearms (he had a trick of shooting ping-pong balls in mid-air during games of table tennis). When the war ended, he continued his pursuit of action-man status by setting himself up as a shark hunter off the coast of Skye, but the business failed when the figures didn't stack up.

Not all was lost, however, since Maxwell's experience of hunting basking sharks – leviathans measuring up to 8m in length – provided the material for his first book, Harpoon at a Venture (1952). It immediately established his reputation as a romantic writer who laced his lyrical descriptions with a hefty dose of gloom and gore. "Harpoon at a Venture is about as far from consolatory nature writing as can be," says Robert Macfarlane, author of The Wild Places and a scholar of the genre. "That's what makes it, and Ring of Bright Water, so fascinating. They represent, in their psycho-dramas, their sublimated sexuality, their flares of misanthropy and their visionary violence, part of the dark side of British nature-memoir and landscape writing."

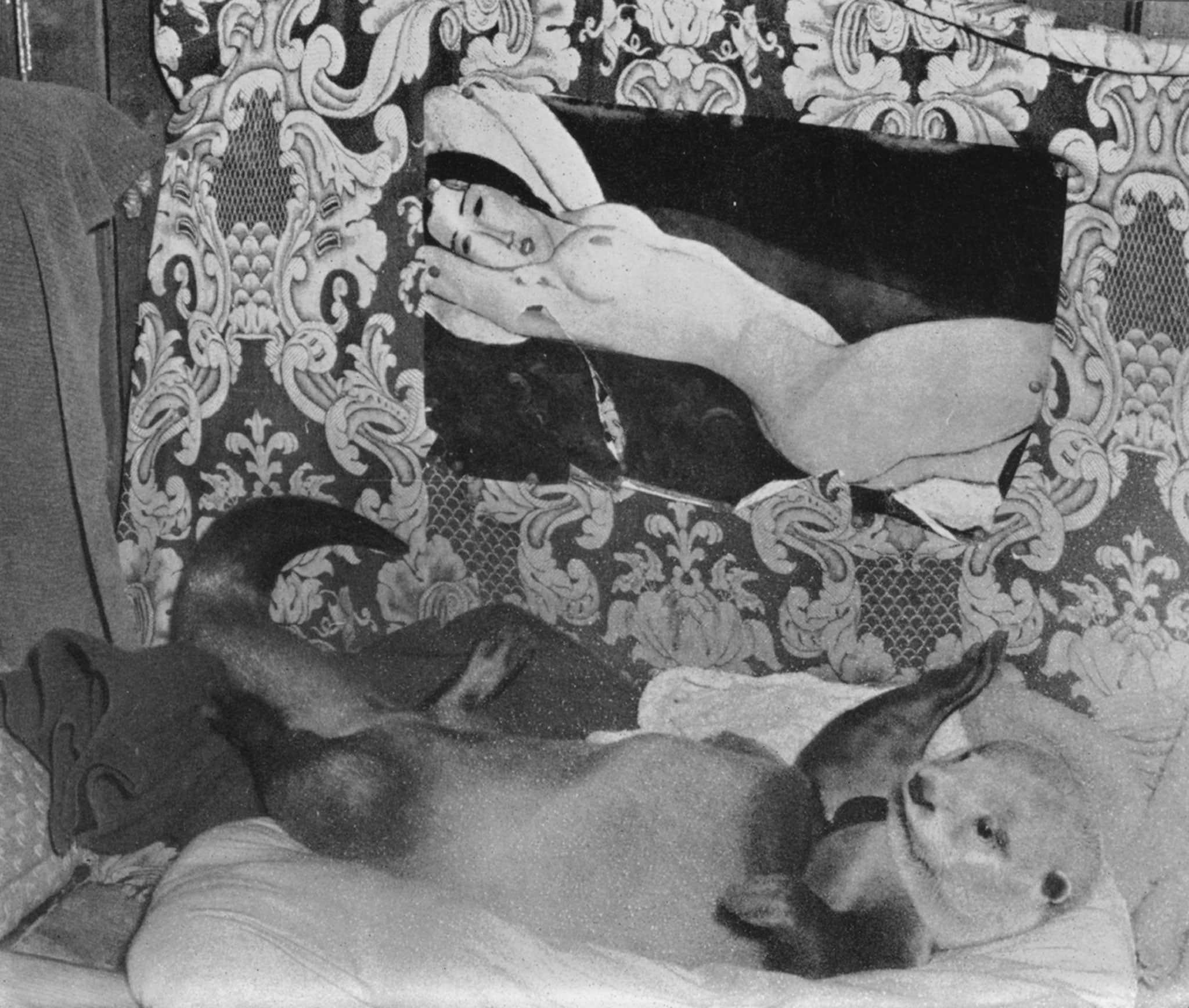

But as well as craving adventure, Gavin also sought someone or something on which to lavish his affection. Although he had several relationships with younger men – his taste, he said, was "for youth and beauty" – his eternal adolescence made it impossible to sustain these relationships for long. Instead it was with otters, at the age of 41, that he finally found the kind of love he had been searching for – a love he called a "compensatory passion" for his pain.

In Ring of Bright Water, Maxwell described this feeling as "a thraldom to otters, an otter fixation". He realised, he wrote, that Mijbil meant more to him than most human beings he knew, and he was not ashamed of it. Kathleen Raine, the poet with whom Maxwell formed a tempestuous friendship and from whose poem the line "ring of bright water" comes, referred to Mijbil as "our animal-child". And when Maxwell briefly married, his wife even talked about producing "a cub" for him, although there never was a baby.

It was the tragedy of Gavin Maxwell's life that Ring of Bright Water was both his greatest moment and the destroyer of his idyll. Suddenly he was famous – the book eventually sold more than a million copies – and people found their way to his sanctuary and shattered his peace.

They also brought him animals; he was initially pleased to have Teko, the male otter who became as famous as Edal, but his home quickly turned into a menagerie. Over the eight remaining years of his life he lurched from one crisis to another: Teko and Edal savaged their keepers (Terry Nutkins, later a TV naturalist, lost two fingers) and had to be fenced in; Maxwell squandered all his new-found wealth on fast cars, boats, booze and two storm-lashed islands; and finally, and worst of all, in January 1968 the house at Sandaig was destroyed in a fire during which Edal was burnt to death in her enclosure. All of this – including his disastrous 15-month marriage – Maxwell chronicled in two sequels to Ring of Bright Water before he succumbed to lung cancer in 1969 at the age of only 55.

At the time of Maxwell's death, he was fixed in the public imagination as the cuddly otter man, as portrayed by Bill Travers in the loosely adapted film version of Ring of Bright Water released in 1969. The actress Virginia McKenna, co-founder of the Born Free Foundation which campaigns against keeping wild animals in captivity, starred alongside her husband in the film. Looking back, what does she think now about Maxwell and his otters? "It's difficult, she says, "because there was this huge love Gavin had for animals. I suppose there was a conflict in him, knowing that some day they ought to go free – and he did let some go. But he was like a man in two parts; the bit of him that adored nature and the wild creatures, the other part that needed this relationship with them, maybe because he didn't have many fulfilling human relationships."

The movie image of a jovial Maxwell and his spirited girlfriend gradually became tarnished as three books were published that revealed a more truthful picture. First, in 1976, the writer's friend Richard Frere published a memoir, Maxwell's Ghost, which publicly exposed Gavin's homosexuality for the first time. It also reported the violent rows and bitter fallings-out between Maxwell and his young otter keepers.

More sensational was Kathleen Raine's memoir, The Lion's Mouth, published in 1977. Although Maxwell had alluded to the part she played in some of the most critical moments of his life, no one could have guessed at the more outlandish details. She revealed how she had been in love with him and how, when he cruelly ejected her from Sandaig one night, she had laid a curse on him. "Let Gavin suffer here, as I have suffered," went her invocation. By a cruel twist of fate, it then became Raine who caused Maxwell's greatest suffering when she allowed Mijbil to run wild on the night he was killed. "I myself became the agent of the vengeance I had worked," she wrote. Maxwell found out about Raine's curse much later, and believed it to be the explanation for everything that went wrong in his life, including the devastating fire.

An authorised biography of Maxwell by Douglas Botting, published in 1993, celebrated his genius as a writer, but did little to dispel the growing picture of him as an egotistical snob who betrayed his friends, neglected his pets and left a trail of destruction in his wake.

There is one person, however, who knew Gavin well and who is prepared to defend his reputation. Jimmy Watt, who appears as a floppy-haired boy in many of the pictures in Ring of Bright Water, was a 15-year-old school-leaver when he joined Maxwell as an otter keeper in 1958. He remained close to the writer and eventually inherited his estate, including the rights to his books. Now over 70, he lives in Glenelg, close to Sandaig. "One thing I would like to say about Gavin is that if he was a friend of yours, he'd always be there for you," he tells me. "He helped a lot of people, paid for their education, and really looked after them. A lot of it was unsaid and unknown. He was like a father to me, so I have a great deal of affection for him."

Watt accepts that our attitude to keeping wild animals has changed, but defends Maxwell's reasons for taking on Edal and Teko. "Both the otters were African; the natives had dug them out of the river banks and given them to the people who brought them to Scotland. They couldn't take them back to Africa, so they were homeless.

"It was different with Mijbil, but the only alternative for Edal and Teko would have been to put them in a zoo. Of course things have changed. I love seeing the wild otters here now, but I wouldn't want them in the house. Outside is where they are happiest."

Back on the beach at Sandaig, I'm standing in front of the large boulder that marks the site where Gavin Maxwell's ashes are buried, and where the famous house once stood. It was Jimmy Watt who placed the ashes here, while Kathleen Raine watched from a respectful distance. Just across the meadow is another grave, a cairn erected over the final resting place of Edal. On the morning after the fire, Maxwell asked Richard Frere to bury his precious otter's remains. Frere found her shrunken body, charred and broken, and buried her here, in front of the rowan tree where Kathleen Raine made her curse. On the cairn is a bronze plaque inscribed with Gavin's words: "Whatever joy she gave to you, give back to Nature."

I understand Richard Mabey's reservations about Maxwell's legacy, but as I read these words I can't help thinking of his dazzling descriptions of his happiest days here with Mijbil, and of how Ring of Bright Water so perfectly articulates the need for the human soul to be free. For that alone, I think, Maxwell's greatest work still stands.

'Ring of Bright Water' remains in print (£10, Little Toller Books). A special edition of 200 hand-bound copies, complete with previously unseen pictures, will be published by the Eilean Ban Trust to mark Maxwell's centenary. For more details: eileanban.org

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments