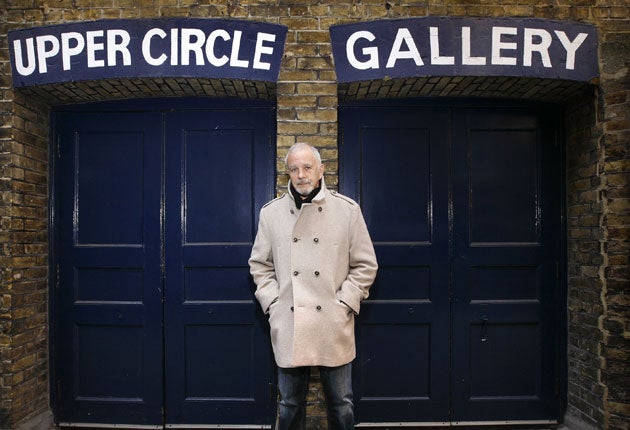

David Essex: More, so much more, than a pretty face

The afterlife of a sex god can be tricky. But the man who decorated a zillion bedroom walls has not been idle, and is about to open in his own West End show. Andrew Johnson meets David Esse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The once flowing brown locks are now a grey, thinning crop; the svelte physique that drove women crazy has rounded out; the smooth skin is tanned and leathery. But the eyes have it. When they fix on you there can be no doubt that the gentleman in faded jeans and hoodie is the former sex god David Essex.

At the height of his success, 35 years ago, the merest sighting was enough to conjure a screaming, hysterical female mob. Boys would copy his hair, his clothes, and his earring. He was sexier, edgier than Donny Osmond and definitely better company down the pub.

And now? Now he is, perhaps, the ultimate baby boomer: born in 1947, he was a teenager in London in the 1960s when it felt like being "at the centre of the world". He rode the social wave that buoyed working-class boys and girls with talent.

At the time, he and his pop star contemporaries were expected to last for 18 months. Now, to an extent like his elders Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney, he can tap into an audience that spans across the generations.

The comparison is not as fanciful as it might seem. Like them, his music was fresh and original and possessed mass appeal. He has sold millions of records, topped the charts with songs such as "Gonna Make You a Star" and "Hold Me Close". His films such as That'll Be the Day were box-office smashes, as was his appearance in the lead role in the musical Godspell.

There was, for a time, Essexmania. After one double performance at the Liverpool Empire, the first house of 3,000 people refused to leave. After the second gig there were 6,000 hysterical fans to battle through. The police gave him one of their uniforms to wear as a disguise, but they forgot about his shoes.

"So we came out but I had these red shoes on which everyone spotted. One policeman went up in the air and it finished up with this sergeant using me as a battering ram going through thousands of people; chucking me in the back of a Land Rover, and then we were under siege in this police station in Liverpool until about six in the morning."

The fans don't besiege him any more, but they haven't abandoned him either. Even now there is a stack of fan mail in his dressing room, which he has occupied for one day. He can still sell out a 50-date tour with no advertising. And he's just brought his new musical to the West End.

"Whether it's British bad taste I don't know," he says of his enduring appeal. "But it's surprising. It's better now because the fact that you were on stage and breathing the same air was enough to drive some people round the bend; mental. Whereas now there is a relationship, if you know what I mean."

We're sitting in his dressing room at the Garrick Theatre in the West End of London where he is preparing his "musical drama" All the Fun of the Fair which opens on Tuesday. I ask, jokingly, if he has any riders – the kind of ridiculous comforts that spoilt rock stars request in their dressing rooms.

He looks at me incredulously. "Nah. Why would I want to bother with any of that?" There's a hint of steel behind his reply.

In an age where many stars make a big noise about saving the world, Essex remains firmly grounded. Where others make a hoohah about their 10-minute trips to Africa to be snapped holding a starving baby, Essex talks about the time he spent with the charity Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) in Uganda.

"It was great, I taught football and a bit of drama and had a go at English as well. They had this flagship teacher training college at a place called Nkozi, a little hut; no water, no light. I did that for two months and I still get letters. They walked, this is what I'm saying, they walked 12 miles to the airport just to wave goodbye. Incredible. That gives you a bit of insight into real life."

On a more prosaic note, he claims responsibility for the fashion of men's earrings – "I think the earring was down to me but that was because of the Romany thing (his mother was a Gypsy). I had that earring, I think, since I was about 15" – but seems untouched by pop-star arrogance.

He does admit to wishing he'd enjoyed the adulation more at the time – "It's only happened to a handful of people" – but adds: "Now I've got a bald head I can go anywhere. I can observe and enjoy, whereas in the past I'd have to keep my head down and march forward. I was bemused and bewildered by it. It never sat terribly comfortably with me."

He was once very involved in Amnesty International, travelling to Argentina during the the military dictatorship to speak to families of the "disappeared". He was a patron of VSO, for which he was awarded an OBE.

He grew up in West Ham, east London in the aftermath of the Blitz with his docker father and Romany mother. His family were so poor they had rooms for a while in a mental institution as there was no other housing. The young David played football for West Ham juniors – and Frank Lampard Senior reckons he could have made it as a pro. A trip to a blues club when he was 14 changed all that, however, and his ambition changed to "playing the drums in a black polo neck with a fag hanging out of my mouth in Ronnie Scott's".

After years of touring with a blues band called Mood Indigo he went solo. In 1971 he won the lead role in Godspell and never looked back.

He's even reluctant to take credit for his song-writing. "It's like something takes me over. It's a gift. I'm not a great virtuoso. I've no idea what this process is; it's a very odd thing. It's not particularly fun. It surprises me when I finish it."

It's these songs that have gone into All the Fun of the Fair. He describes it as a "dark and edgy" musical drama, it is not a jukebox musical, nor a musical of any kind he insists – "there are no jazz hands" – and it's set in a fairground.

"The sense of freedom (of fairgrounds) appeals to me. My Mum used to say to me, a land without Gypsies is a land without freedom." He talks about freedom a lot. Sometimes this makes him sound like a grumpy old man, moaning about health and safety regulations that won't let him have a real wall of death on stage; but there's more to it than that.

He's just completed a screenplay called Tramp, for example, because, he says, we don't care for eccentricity or individuality anymore. "When you see old fellas winding out of Tesco you don't know their background or life story and there seems to be a lack of respect for older people. In Africa, if the older statesman speaks, everybody listens. If the older statesman speaks in the Western world, everyone goes 'Oh, silly old sod. Shut up'. What worries me about modern society is how inhibited it is. I'd like to see more eccentrics and more freedom, less surveillance and all of that stuff. I think the world would be a richer place if there were less rules and regulations."

All that said, he has no time for famous peers who complain about their lost freedom.

"To sacrifice personal freedom to gain creative freedom is a fair enough price. I don't take it for granted that people are still interested in what I do. That's tremendous because they give me a chance to do what I want to do. I never planned anything. I never had an image. I was just being me. If it hadn't worked out I would have done anything with freedom. I would have driven a truck across Europe."

Curriculum vitae

1947 Born David Albert Cook in Plaistow, east London. Plays for West Ham juniors. Deliberately fails his 11-plus in order to go to the football-playing local secondary school.

1961 Works for a funfair after "forgetting" school for a few months. Learns the drums after seeing his first band in the West End of London.

1963 Cuts his first record – "And the Tears Came Tumbling Down" – for Decca and begins touring in a Bedford Dormobile with nine boys – East End Mods and West Indians – "playing depressing blues music".

1966 Meets his first wife, Maureen.

1971 Goes solo and stars in Godspell. His daughter, Verity, is born.

1973 Releases Rock On which sells one million copies. Stars in the film That'll be the Day with Ringo Starr.

1974 "Gonna Make You a Star" gets to No 1. Stars in Stardust. Voted UK's number one male singer.

1975 "Hold Me Close" becomes his second UK number one.

1978 Plays Che Guevara in the original production of Evita. His single "Oh What a Circus" reaches number three. His son, Danny, is born.

1980 Stars in film Silver Dream Racer. Separates from his wife.

1985 Co-writes and stars as Fletcher Christian in the stage musical Mutiny.

1997 Marries Carlotta Christy.

1998 Twin sons Bill and Kit are born.

1999 Awarded OBE for services to VSO charity.

2008 Writes All the Fun of the Fair.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments