Bob Beamon: The Beamon dream

Emulating the American's stunning 1968 feat will inspire many in London, but, he tells Simon Turnbull, he nearly did not make the long jump final

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

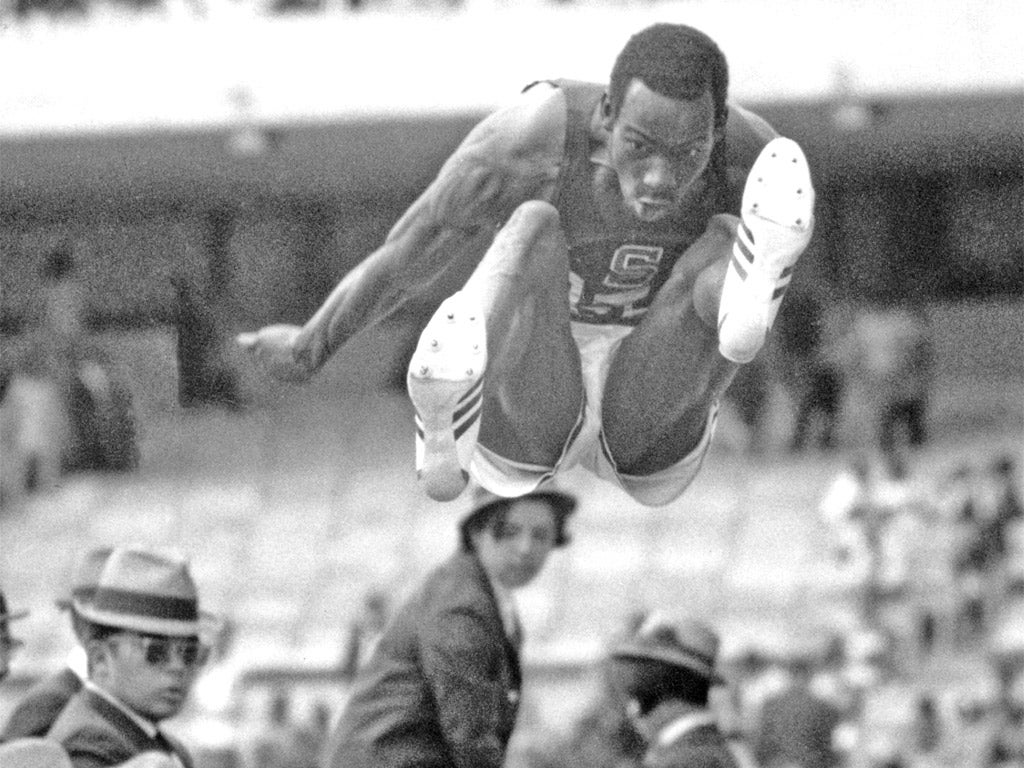

Your support makes all the difference.It was a giant leap for man. Forty-four years on, the grainy mental image endures. On 18 October 1968 Bob Beamon set off down the long-jump runway at the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City and soared through the thin air like Icarus ascending.

It was a stunning sight to behold on black-and-white television back then – just like Neil Armstrong's one small step for man from the foot of Apollo 11 on to the Sea of Tranquility nine months later. In sporting terms Bob Beamon's leap was out of this world.

It was off the scale of the sophisticated optical measuring equipment. When officials slid the marker down the rail to the point where the 22-year-old New Yorker had hit the sand, it fell off the end. They had to get an old-fashioned steel tape.

At the time the world record stood at 8.35m, held jointly by Ralph Boston, Beamon's US team-mate and confidant, and the Russian Igor Ter-Ovanesyan. When the scoreboard eventually flashed up 8.90m, though, Beamon remained unaware of the scale of his achievement. The US track and field system still used imperial measurement and Beamon suspected he might have been an inch or two over the world-record distance, which converted to 27ft 4.75in.

When Boston embraced him and said "Bob, you jumped 29 foot," his legs buckled under him and he collapsed. In fact, he had jumped 29ft 2.5in. His one giant leap had advanced the world record by 21.75 inches, 55cm.

It remains the single most stunning performance in Olympic track and field history, Usain Bolt's 9.69sec 100m run in Beijing four years ago notwithstanding. It spawned the phrase "Beamonesque", which is routinely applied to major advancements in athletic performance, such as those made by Bolt on the sprint front and, lest it be forgotten, by our own Paula Radcliffe in the marathon.

"Well, the first time I heard it I didn't even know how to spell it," Beamon said yesterday, sitting in the Haldane Room at University College London. He had a mischievous twinkle in his eye. "I thought it was very nice of people to associate me with that," he continued. "There have been some great performances at the Games – Michael Johnson, Usain Bolt. And during my time, we had an incredible US team that pretty much dominated every track and field event in '68."

Over Beamon's left shoulder was a snapshot of one of his victorious team-mates from those '68 Games, Al Oerter. There was also a vivid artwork produced by the four-time Olympic discus champion, who founded the Art of the Olympians museum in Fort Myers, Florida.

Beamon, now 65, is the chief executive officer of Art of the Olympians and is in London with a pop-up exhibition that runs at University College London until 13 August. Admission is free and the exhibits on display also include one of Beamon's graphic designs. His artwork has appeared on ties and scarves for several years now.

"I got the idea from Jerry Garcia," he said, referring to the late frontman of the Grateful Dead. "He had art pieces that he turned into artwork on ties. It was like, 'Jerry is just as famous not living as he was when he was living.' He kind of inspired me.

"That piece I did over there just came to me. It started from scratch. I didn't have a plan for it. I just put it together, so somebody upstairs encouraged me."

Next to Beamon's artwork was a photograph of him in mid-flight in his 8.90m jump in Mexico City, some 6ft above the ground. "When I first saw this picture, someone asked me, 'Did you know you were going to jump that far'?" he reflected. "I said, 'You know, while I was up in the air I looked at my watch and noticed it was like an hour that I had been airborne.'"

The mischievous twinkle was back. "It was a record that I didn't expect," he continued. "I tell you I was completely in awe. And I'm still celebrating the accomplishment now –because I come from a different type of lifestyle than most would think."

Beamon had a tough upbringing in South Jamaica, Queens, the New York City neighbourhood from which the rapper 50 Cent later emerged. He relates in his autobiography The Man Who Could Fly how his elder brother, Andrew, was brain-damaged at birth by the kicking his mother received from his father when she was pregnant. Beamon himself was repeatedly beaten, following the death of his mother when he was just eight months old, and was raised by his grandmother.

He became a member of a street gang in Queens and witnessed a friend being stabbed to death. He took up athletics while at reform school and by 1968 was established as one of the world's leading long jumpers.

Beamon travelled to Mexico as the favourite but he had a reputation for being prone to fouling and had also been without a coach for six months. He was suspended from the track team at the University of Texas at El Paso for refusing to compete against Brigham Young University as a protest against the racial policies of the Mormon church.

Beamon almost came to grief in the qualifying round, fouling the first two of his three attempts. Boston, who had been helping to coach him, told him to take his final effort from a mark a foot before the board and he made it through comfortably at the third time of asking.

Even then, he thought he had blown his chances when he broke with normal practice and engaged in sexual intercourse the night before the final. Instead, it was his rivals who were left in a state of anti-climax after his first-round jump the next day.

Welshman Lynn Davies, the defending champion, turned to Beamon and said: "You've just destroyed this event." He was right. No-one else could manage to venture farther than 8.19m after Bob Beamon's quantum leap.

The Beaches of Fort Myers and Sanibel 'Art of the Olympians' is at the Main Wilkins Building, University College London until 13 August – free admission

Oldest records

1968: Men's long jump

American Bob Beamon leapt to a distance of 8.90m. Still stands.

1980: Women's 800m

Russian Nadezhda Olizarenko's time of 1min 53.43sec led a Soviet 1-2-3 on home soil. Still stands.

1980: Women's 4x100m relay

East Germany retained their track title in 41.60sec. Still stands.

1980: Women's shot-put

East German athlete Ilona Slupianek managed 22.41m to win her only Olympic gold. Still stands.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments