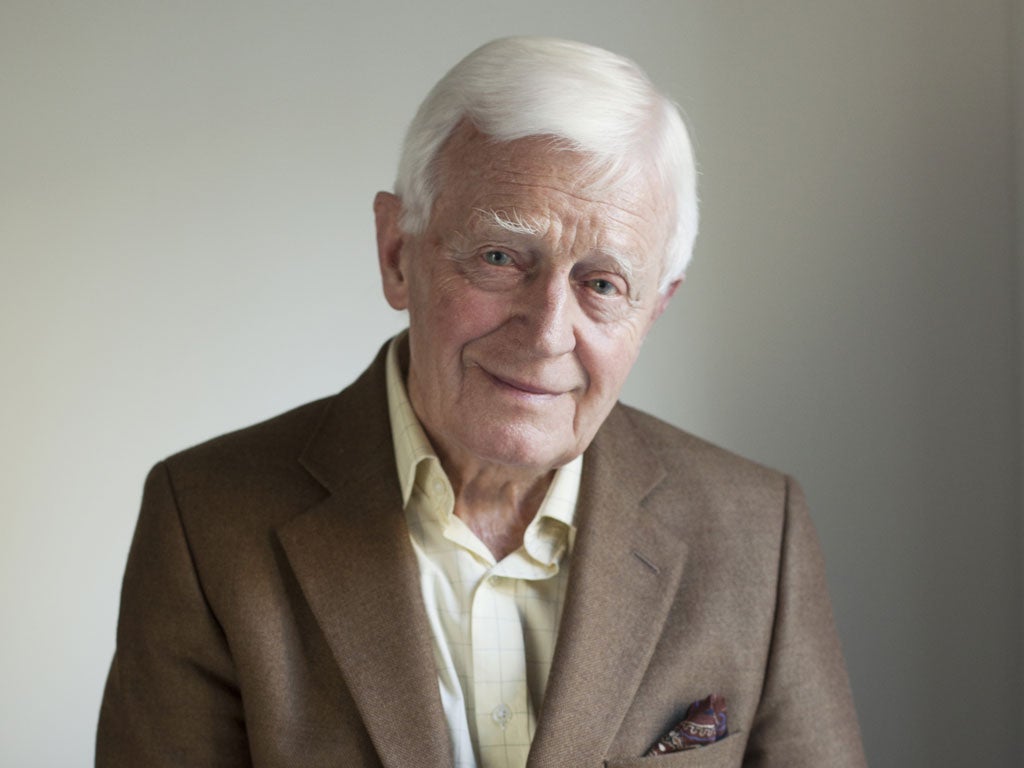

Alan Grieve: Is the future of the arts in his hands? A serial giver owns up

As a new contemporary art gallery opens on the beach at Hastings, Simon Tait asks the man behind The Jerwood Foundation about nepotism, saving theatres, and picking up the tab for British culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The name Jerwood is ubiquitous in the arts, adorning playhouses, dance studios, rehearsal spaces, student bursaries, prizes ranging from drawing to dance, exhibitions and now an art gallery. Jerwood is the great enabler, the crucial partner without which the Royal Court would have closed. And Jerwood is controlled absolutely by a single, 84-year-old retired lawyer, driving it on a path of cultural philanthropy.

Alan Grieve is a 21st-century Dickensian. He was the bright young solicitor who earned the trust of a self-exiled millionaire called John Jerwood (even the names have a Dickensian ring), and with the fortune left on Jerwood's death he created his own empire. In 20 years, Grieve has given £90m to the arts, building theatres, dance houses, libraries and creative facilities, and helping the careers of countless young artists, performers and craftspeople.

At Hastings, among the fishing boats and net sheds on the Stade, a working beach where the Peggottys of David Copperfield might easily live still, Grieve has built the latest and perhaps his last in a line of capital arts projects. For a while there was a vociferous protest against the plan – an effigy of a gallery was even burnt on the beach long before any designs had been drawn up – because it would be seen to clash with historic Hastings, but the campaign ran out of steam when the understated architecture emerged as being rather complementary.

Costing a modest £4m in an £8.5m development partnership with the local authority, this seaside gallery joins the South-east coast "string of pearls" of Margate's Turner Contemporary (£17m), Eastbourne's refurbished Towner (£8.5m) and Bexhill's De La Warr (£8m). The Jerwood Gallery opens on Saturday, devoted to 20th-century British art.

Grieve is the last of the Victorian "entrepreneur philanthropists" – his own phrase – autocratic, single-minded and the only recipient of a National Lottery grant to give it straight back. When searching for talent to help him, he is inclined to look no further than his own family: his art historian daughter Lara Wardle is the new director of the Jerwood Foundation, and his son, Tom, is the architect of the new gallery in Hastings. The eldest of his five children is "fashion's first lady", Amanda Harlech of Chanel.

Grieve has personally assembled the art that the gallery has been built to house, filling a hole in what was on offer, he believes. Latterly, this has been done with advice from Lara, former associate director of 20th-century British art at Christie's, and from the new director of the gallery, Liz Gilmore, who was brought from the Arts Council where she had been head of visual art. "It is a private enterprise for the public benefit, and that's true philanthropy," he says.

Grieve was 30 when the senior partner of his Gray's Inn law firm asked him to look after a "tricky client", tricky because he and his pearl business were based in Tokyo. Grieve travelled the world for Jerwood as his business lawyer, becoming his friend and confidant. In the mid-1970s, he was given power of attorney to create a charitable foundation, the chief interest of which, initially, was Jerwood's old school, Oakham, to which he gave close to £8m. "He had no children but he had money and he liked education and the arts," Grieve says. "He did what he wanted to do."

When Jerwood died in 1991, Grieve took control of an organisation with huge assets but no order. Even to establish the extent of them took him two years. He acquired property, principally the handsome Fitzroy Square townhouse that was the Jerwood headquarters until last autumn, and he invested shrewdly enough to treble the assets. His CBE came in 2003.

Grieve has a Micawber-like respect for good financial management – "It isn't my money, after all" – and an extreme aversion to paying what he considers over the odds. He made a handsome profit for Jerwood when he sold Fitzroy, moving the Foundation to a converted Notting Hill mews.

The art collection, he estimates, is worth around £6m but cost only £1.5m. He has never paid more than £100,000 for a work, yet has assembled a canon of British art which started with Frank Brangwen and David Bomberg, and has progressed through Sickert, Augustus John, Stanley Spencer, Winifred Nicholson, L S Lowry, Christopher Wood, Terry Frost and Keith Vaughan. He has added Jerwood Painting Prize winners such as Craigie Aitchison, Maggie Hambling and Prunella Clough, and the gallery will show a large representation of the collection, plus temporary exhibitions, starting with Rose Wylie. "It's still organic, we'll continue to buy, but sometimes we fail at auction because we're not prepared to pay prices we can't afford," he says. Most recently, Lara failed to buy a Tristram Hillier when bidding broke Jerwood's ceiling.

It was the painting prize that started Jerwood's serious arts sponsorship in 1994. At £25,000, it was the richest of its kind when it was phased out in 2004. Then came the first major capital commitment, the Jerwood Space in Southwark, south London, a much-needed dance and drama rehearsal facility. The rents are calibrated according to what the client can afford, and this is the project for which Grieve applied for lottery funding.

"I made an application, like a lot of people in those euphoric days, and it took quite a while, very bureaucratic, but eventually we got a grant. I only kept it a few weeks before I realised that the Arts Council would want to bear in on me, tell me I hadn't done this or that. So I rang up Gerry Robinson [then chairman of Arts Council England] and asked to whom I should make the cheque out. I think you'd say he was taken aback."

When the Royal Court was on the brink ofclosure, considered unsafe in the mid-1990s, Grieve offered £3m to help rebuild it. A news story suggested he insisted the quid pro quo should be a renaming to "Jerwood Royal Court" but that Buckingham Palace vetoed the idea. "Absolute nonsense," he retorts.

The Royal Court rebuild was by the architects Haworth Tompkins for whom Tom Grieve later worked, but his own practice, HAT Projects, was born after Jerwood's Hastings scheme was already under way. Hastings was chosen as a site, with the advice of a planning consultant, Hana Loftus, as much for the amenable attitude of the local authority as for the seafront site, and Loftus later joined HAT as Tom's co-director. "When we were being considered, I knew nepotism would come up, and I asked Hana's advice," Tom Grieve says. "She told me to look at the project and nothing else, and then make my decision if the offer came. As it was, my father pretty much left us to do our job." Alan Grieve, unfazed, refers to "enlightened nepotism". He and his co-trustees, he says, chose, from a competition, a practice which came in at "a bargain" £4m, well below any other.

His enlightened philanthropy, however, will never realise the dream of the Culture Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, of taking the burden of arts funding from public subsidy. "Politicians will always do that, whenever there are cuts they will try to come up with an alternative [to public funding of the arts], but there isn't one," he says, "not without the tax breaks American givers get, the difference between America and Europe. Philanthropy will continue to work alongside subsidy here. It won't replace it.

"Philanthropists have always been key to the arts, particularly to the Victorians when there was no state subsidy, and sponsors like Cadbury and Leverhulme were the nearest thing," he says. Now their equivalents are the foundations set up by Paul Hamlyn, Isaac Wolfson, W Garfield Weston and Jerwood – but without the colossal pound power of a century ago.

The new philanthropists are business leaders who can see to the end of a project and make assessments accordingly, without "blind chucking money at something" he says. "The thing about Jerwood is, there must be tangible identifiable results before we start. That's absolutely characteristic of us." And very characteristic of Alan Grieve.

The Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, opens Sat (01424 425809, jerwoodgallery.org)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments