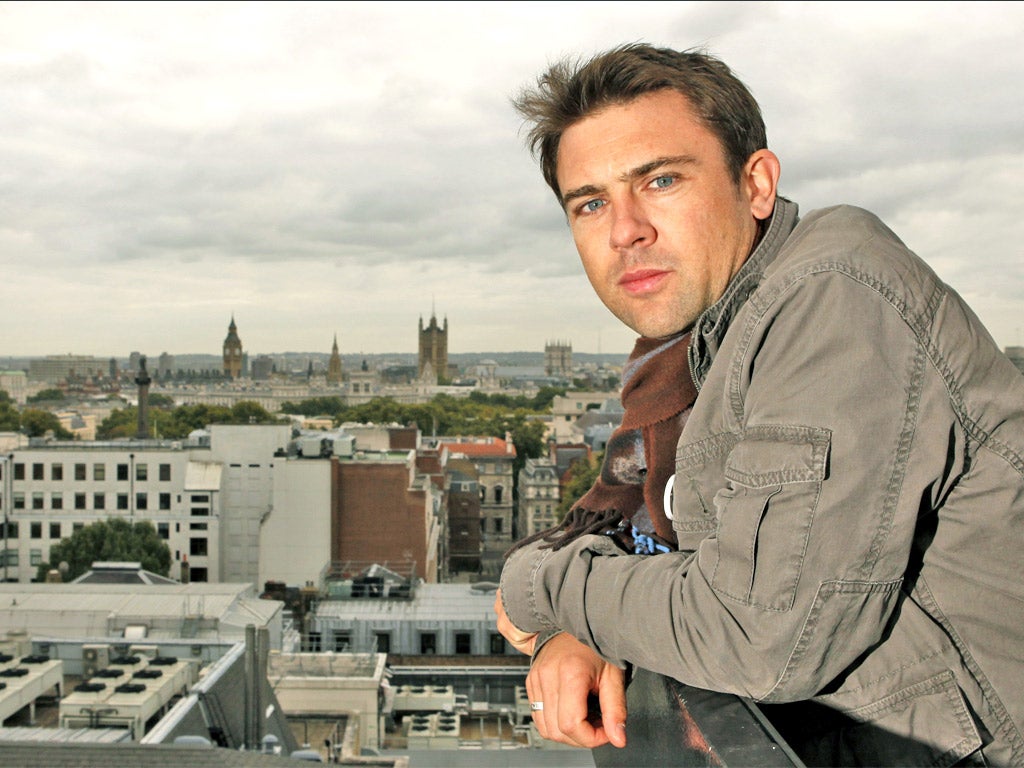

A writer who's hard to resist

Owen Sheers on the importance of truth-telling.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."It's a bit of a perfect storm," says Owen Sheers, still a little out of breath from his bike ride across town. The writer, 37, has spent the week shuttling between red carpets in London and his hometown of Abergavenny in South Wales for the premieres of Resistance, a new film starring Andrea Riseborough and Michael Sheen based on his debut novel.

In between, he's just started rehearsals on a new play, The Two Worlds of Charlie F, which will be performed by a company of 30 wounded and recovering soldiers as part of Trevor Nunn's next season at Theatre Royal Haymarket. Meanwhile, he's just spent a week in Wales, "back at the coalface of poetry", giving readings and workshops in his day job as one of Britain's brightest young poets.

The producers of Resistance call their screenwriter a "multi-platform literary star". Sheers wrinkles his nose. "That's a spectacularly ugly phrase. It makes me sound like an app." Unpoetic it may be, but it's also apt. In the 12 years since his debut collection, The Blue Book, was nominated for the Forward Prize and Welsh Book of the Year, the rugby player from the valleys has shown himself to be a versatile talent. It's the "different engines of storytelling" which drive him, he says, whether writing verses hymning rural Welsh life, co-creating a three-day Passion play with Michael Sheen or presenting A Poet's Guide to Britain on the BBC.

Resistance is his first foray into film. The 2007 novel imagines that the D-Day landings have failed and Wales has been occupied by the Nazis. One morning the women of the Olchon Valley wake up to find that all the men have disappeared into the hills to muster a resisting army. It's counterfactual history in the mould of Robert Harris or Philip Roth, but it's rooted in fact. Sheers was working as a tiler in the valleys one summer when he heard about the Auxiliary Units – secret civilian networks which, in the event of invasion, would have formed a British resistance. The stories of local vicars and teachers being primed to spy on the occupying Germans and farmers hiding weapons in underground bunkers, ready to flee their homes to fight in the Welsh mountains, stayed with him. In time, they became Resistance, a war novel which focuses not on fighting but on the uneasy means of survival open to the women who are left behind.

"I was never interested in writing the Boy's Own version of war," says Sheers. "It's exactly that kind of approach that masks what war really is. It's more interesting to work in the more complex territory of where the lines between resistance and collaboration blur. I wanted to use what looked like a Len Deighton-ish hook – occupied Britain – to write an anti-war novel."

Directed by first-timer Amit Gupta, the film features a powerfully restrained performance from Riseborough as Sarah, the farmer's wife torn between her absent husband and the kindnesses of a German commanding officer. It's the bleak majesty of the Black Mountains, though, which steals most scenes. Sheers insisted that the film was shot in and around the borders, where he grew up. When it came to the shoot, he roped in everyone from his parents to his old RE teacher and his dentist to help out with crowd scenes, props, even, in one case, the loan of a horse. Riseborough, meanwhile, enrolled in aqua aerobics at the local leisure centre to immerse herself in the valleys lilt.

Sheen came on board after working with Sheers on The Passion, a three-day play which unfolded over the Easter weekend in Sheen's hometown of Port Talbot. In Sheers' Neath-flavoured take on the Bible, The Last Supper became pork pies and beer at the Social Club (with music from the Manic Street Preachers), while the Garden of Gethsemane was a scrubby patch of grass on a council estate. At the climax, a bearded and bloodied Sheen was "crucified" on a roundabout in sight of the steel works and a crowd of 12,000.

"I was adamant that everything should come from the town itself," says Sheers. "We met a roofer who talked wonderfully about the view over the town from the rooftops. As soon as we interviewed him, we thought 'that's our God'."

It's tempting to ascribe both projects to some innate Welsh gift for lyrical storytelling, but, while namechecking his compatriots Dannie Abse, Gladys Mary Coles and Robert Minhinnick as influences, Sheers is not so sure. "I've always preferred to call myself a writer from Wales rather than a Welsh writer," he says. "No writer wants to be constrained by their nationality." Born in Fiji, bred in Wales, and now living in a loft conversion in Hackney, his writing has taken him from Zimbabwe (the setting for his first non-fiction book, The Dust Diaries), to residencies at Wordsworth's cottage in the Lake District and New York Public Library. "I do enjoy being a writer away from a desk, working with people who aren't writers."

He has spent the last month interviewing soldiers injured in Afghanistan for his new play, which will use the verbatim techniques of London Road and Black Watch to capture the horrors of war and the pain of homecoming. Catch 22 meets Beckett, apparently. He's also been commissioned by Radio 4 to write a long war poem to be broadcast over five days next year. A modern-day Odyssey, it will tell the tale of a young soldier returning home to Bristol from the front line.

"The main reason I've been writing about war is because we've been at war for 20 years. If you want to send people to war, then do, as long as you realise it means this. Let's not look away from it."

After university, he briefly considered joining the Army – "but it didn't take me long to realise that the way the Army works was never going to work for me. They need to make you their own man." Instead, he immersed himself in the war poets, playing Wilfred Owen in a play at Hay Festival and writing a play about Keith Douglas which was performed at the Old Vic by Joseph Fiennes. He followed it up with a BBC programme last year. "Never mind all of the acres of very good journalism that's written about war", he says. "The reason we read poetry is that it has the ability to penetrate both solar plexus and between the eyes, simultaneously, in a way that prose doesn't."

Poetry remains his passion. He began writing at a precocious age – poems about the Big Pit mining museum and autumn, which made his teacher cry. "I can remember thinking, in quite a nasty, manipulative, little-child way, 'that's interesting, you put some words on a page, and it does that'. I suspect she cried easily, but I do remember it." Aged 10, he won a competition at Abergavenny Show for a poem in which he found a rhyme for "orange" – a mountain in the Brecon Beacons called the Blorenge. "I won 50p and thought, 'there's money in this poetry game'. I've since been proved wrong."

He read English at New College, Oxford before enrolling on UEA's hit-factory of a creative writing course, where he studied under Andrew Motion, who praised his writing as "sharp, fresh, clear and ambitious." By the time he left, he'd struck a deal to publish The Blue Book – a robust, limpid collection of poems about family, first love and farming life – with Seren, an independent press who operate from above a tattoo parlour in Bridgend. Still only 25 years old, Sheers got a job on The Big Breakfast as a researcher, to pay the rent. By day, he was setting up interviews with Chris Eubank and Steps and inventing outside broadcast ideas for Richard Bacon ("I put the poetry mind to work and came up with 'Streaky Bacon'," he murmurs). By night, he was planning his next book, about a turn-of-the-century missionary to Africa, Arthur Cripps. "It was a quite exciting but quite uncomfortable juxtaposition," he says. "I went from Johnny Vaughan and Kelly Brook to walking across Zimbabwe."

The experience, perhaps, was good preparation for Sheers's subsequent career, as television's face of contemporary poetry. His Poet's Guide to Britain on BBC4 was a blustery, rugged hike through the classics, which saw him declaiming Wordsworth from Westminster Bridge and scrambling around the Orkneys in search of the soul of George Mackay Brown. It's no surprise to learn that his hobbies include riding (at home in Wales) and outdoor swimming (in London Fields lido). He saw the series as a rare opportunity to get poetry – both classic and modern – out to a mass audience. "It was getting contemporary poets in the back door," says Sheers. "The BBC tends to like its poets dead."

Or pretentious. You won't find Sheers pontificating on late-night television, though. "I think I'm more of a readers' poet than a poets' poet, to be honest. Publishers will say, 'Just review that, and of course you should go on The Late Review'. But I don't want to be talking about stuff, I want to be doing it," he says. In the near future that means finishing off his "long overdue" second novel, a screenplay and, finally, hopefully, finding his way back to where he started.

"Poetry is still my first love and the form I want to get better at more than most. Don Paterson very cheerfully said that to write poetry is to work in failure, but it's where I'm most comfortable," he says. "I genuinely think that at the end of your writing life, if you can say that you've written two or three true poems, that's a pretty good hit rate."

'Resistance' is released on Friday

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments