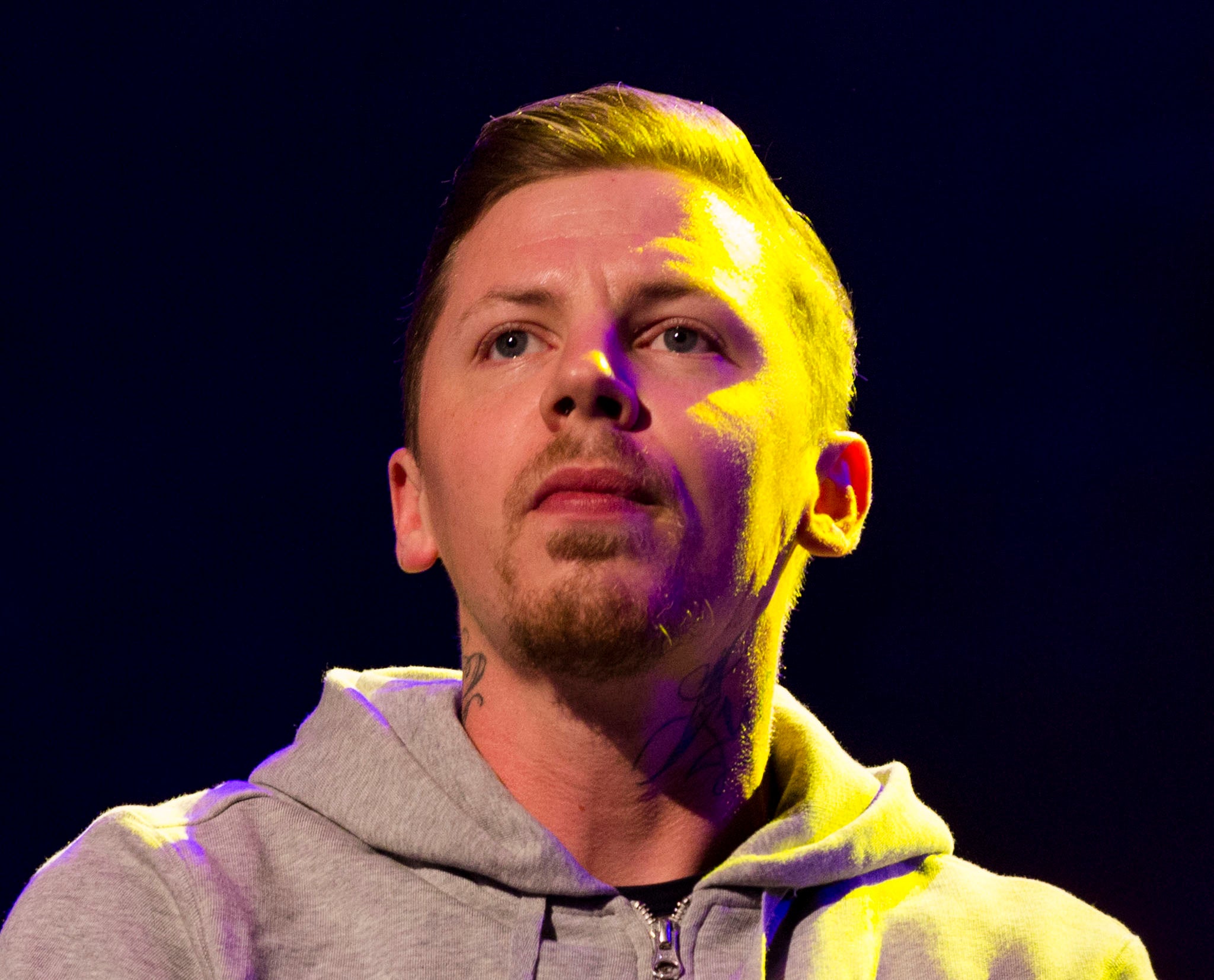

Professor Green urges men with depression to seek help after his father's suicide: 'I wish that he could have reached out to someone'

'I still don’t know what was going through my dad’s mind when he killed himself in a park not far from where he lived in Brentwood,' he writes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If any good could possibly come out of the tragic death of Robin Williams, it’s highlighting the plight of thousands who struggle with severe depression.

Many have been moved by the story of the comedian, who despite being one of the most charismatic and entertaining human beings on the surface, was plagued by inner-demons and mental health problems that would eventually lead to his suicide.

Professor Green is one such person. The rapper, real name Stephen Manderson, has chosen to share not just his own experience of suffering with depression and anxiety, but his wish that his father, Peter Manderson, had been able to seek help before he took his own life in April 2008. He was 24 at the time.

“I still don’t know what was going through my dad’s mind when he killed himself in a park not far from where he lived in Brentwood, Essex,” he wrote in a column for The Guardian.

“I’ll never know. The last time I saw him alive was my 18th birthday. He had been in and out of my life for years. I was brought up by my gran in Hackney, east London, because neither of my parents were capable of looking after me. I just wish that he could have reached out to someone, anyone.”

“I thought my dad was selfish for taking the easy way out,” he continued. “But then I quickly realised that I was the one being selfish for thinking he was selfish. For someone to be able to do that, I don’t think it is cowardice; it’s the only solution they think they have.”

The tragic news was made worse by the fact that the last words he had exchanged with his father had been ones of “anger and hate”, after the pair argued on the phone on Boxing Day some months before.

“If I ever see you again I’m going to knock you out,” Stephen had told him.

“I would give anything to change that,” he wrote. “I never got a chance to say a proper goodbye or tell him that I loved him.”

“Communication is a big problem with us men,” he continued, going on to discuss his own problems. “We don’t like to talk about our problems; we think it makes us look weak. There have been times when I’ve suffered from anxiety and depression. I even had cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and, although that didn’t work for me, I did find that talking about things out loud to someone helped the problem seem much smaller than it was in my head. It’s important to let things out and not to bottle them up.

“Society likes to tell you that you have to be happy all the time, and it’s easy to think that if you’re not happy then there’s something wrong with you. But happiness isn’t permanent, it’s not something you can feel all the time – and neither is sadness.”

He goes on to cite that over 6,000 people took their own lives in 2013, with the most at risk being men between the age of 30 and 44. His father was 43 at the time of his death. His uncle had killed himself two years previously and the youngest of his uncles had died after “allowing himself to fall into a diabetic coma”.

“What happened to my dad and uncles makes me want to deal with things,” Stephen concluded. “I wrote the song “Lullaby” about my experience of depression and how it has affected my life.

“The most important lyrics are the final two lines: ‘Things always change, as long as you give them the chance to.’

“Know that is true. I just wish my dad did.”

For confidential support call the Samaritans in the UK on 08457 90 90 90, visit a local Samaritans branch or click here for details