Otto Feldmann's Diary: 'The cruel breath of history has separated us'

'One’s mind has become so numb, one lives just for the food and the hope. We, the dead who have survived by chance'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 1 November 1914, Otto Feldmann set off for the Eastern front as a Czech officer in the Austro-Hungarian army. He left behind a pregnant wife and two daughters. He wouldn’t see them again for six years, having been forced to travel around the globe to return home. Throughout, he kept a diary, written as a series of letters to his wife, in a hidden notebook. It documents war and captivity, years spent in desolate Russian POW camps, and journeys spanning the length of the early Trans-Siberian Railway. To honour his memory and preserve his story, his family has published the diary for the first time, 100 years since he left for war...

BEFORE THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Otto was born on 10 April 1881 to Julius and Freida Feldmann in the city of Troppau (Opava), then the capital of Austrian Silesia. He had two brothers, Hugo and Victor, and a sister Gusti. In an age of indistinct cultural borders, the family were assimilated Jews, living in a German-speaking region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that would later become Czechoslovakia, and then the Czech Republic.

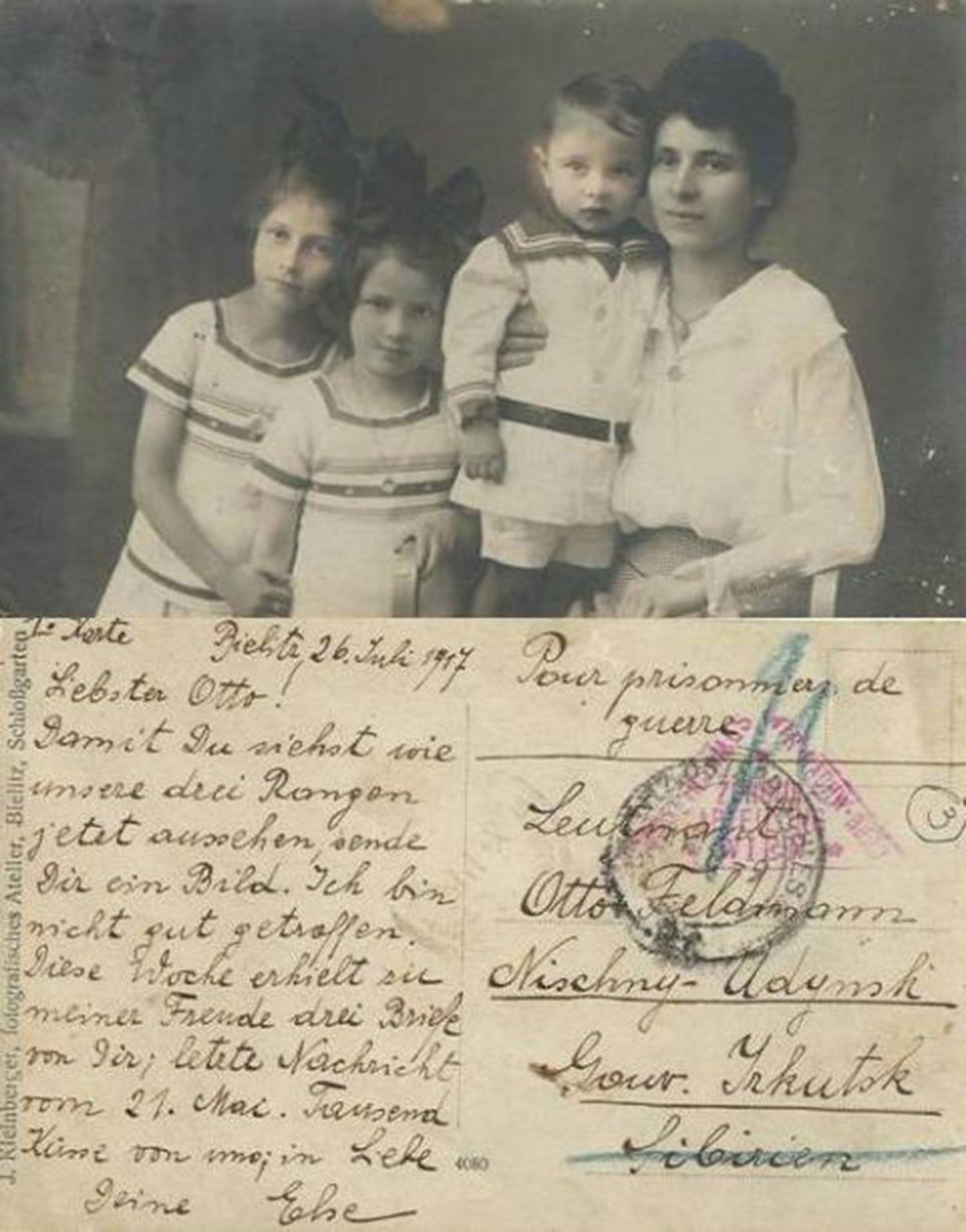

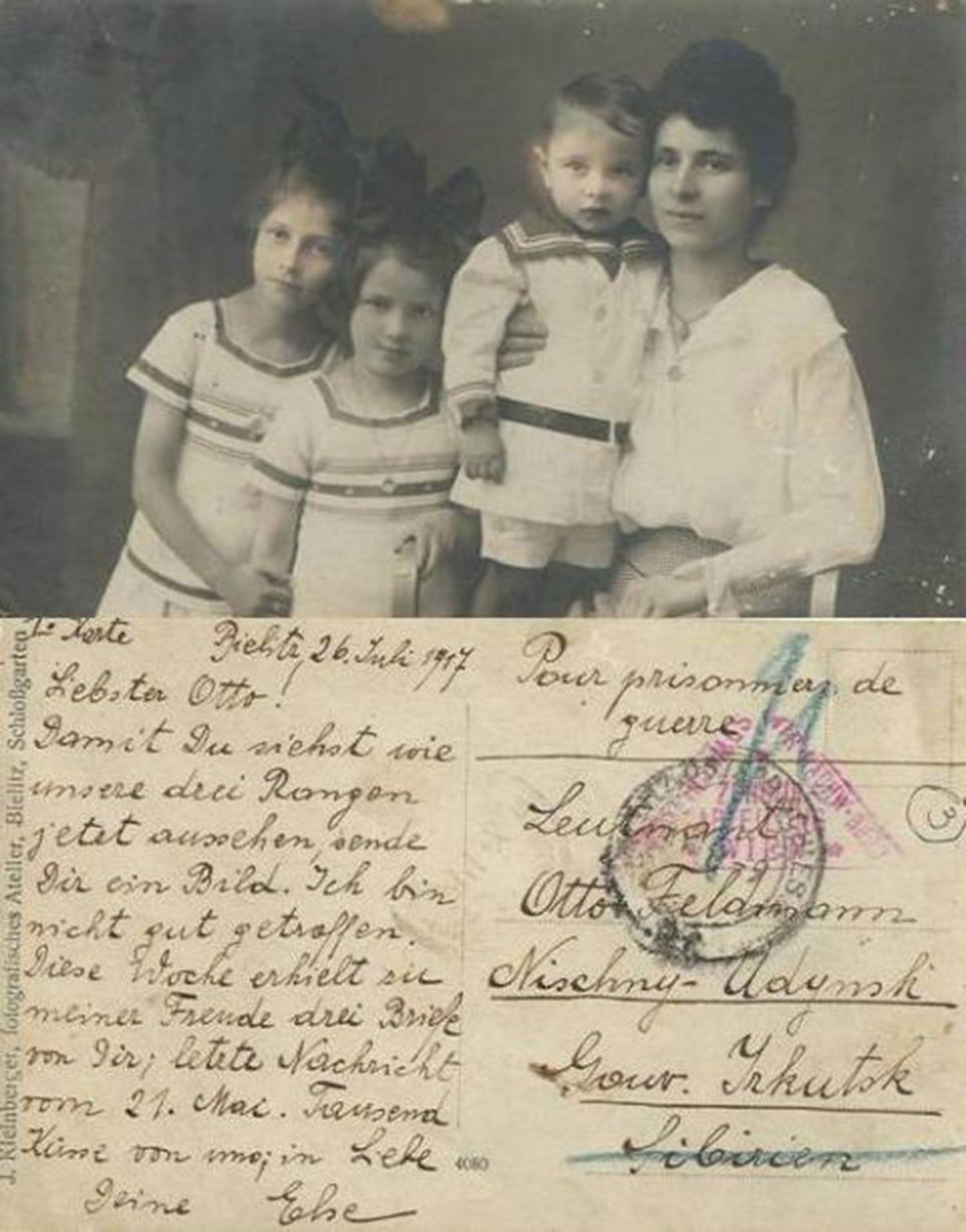

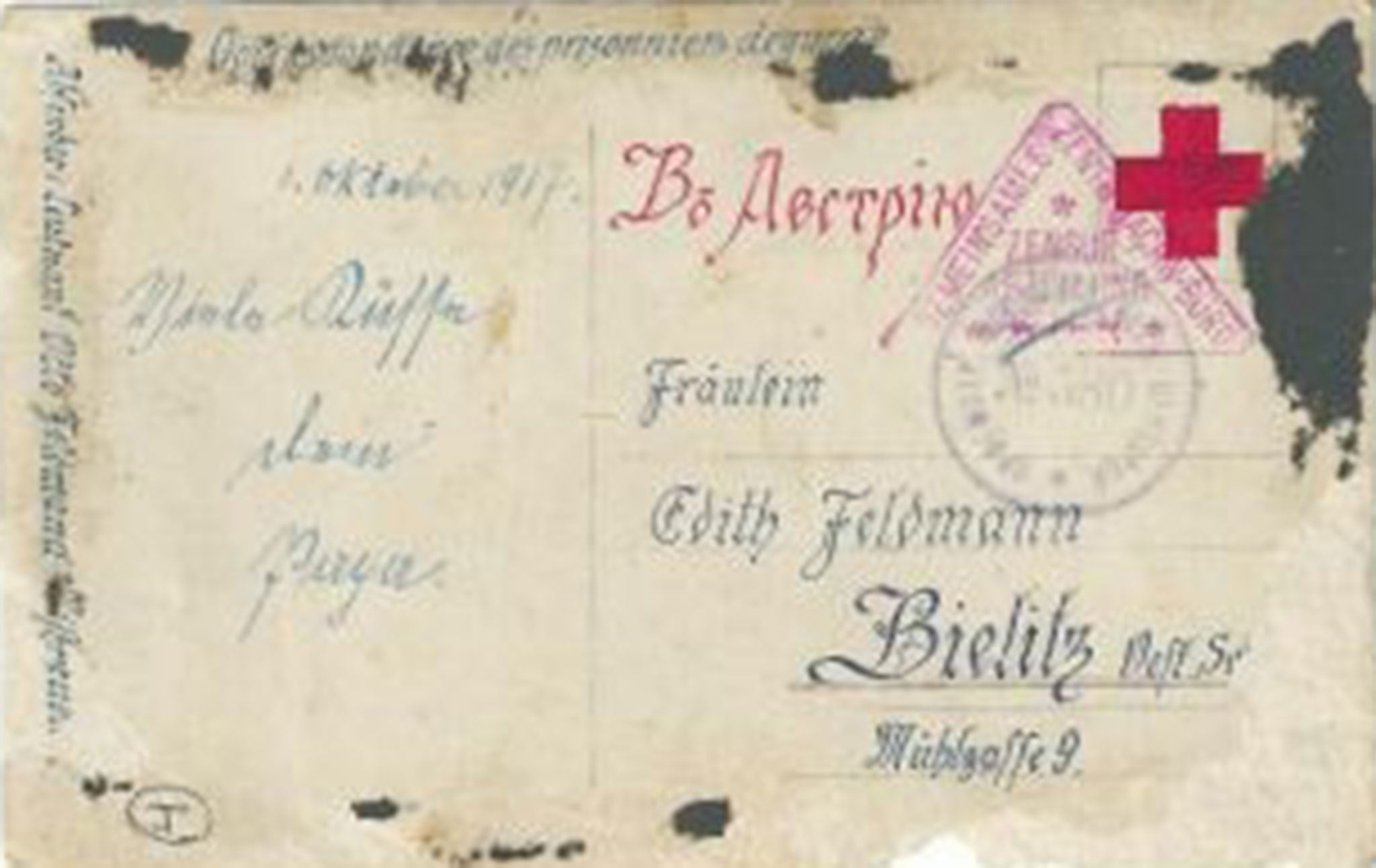

Otto was an idealist who saw the best in everyone, and had many good friends. He studied chemistry at Bielitz (Bielsko) University and specialised in foodstuffs. In December 1903, he sailed to Cuba to learn how sugar was manufactured from cane, and lived there, carrying out his research, for several years. When he left for Cuba he had already met his wife-to-be, Else Kranz, while studying in Bielitz. Her parents ran a student restaurant and they fell in love over dumplings, sauerkraut and whipped cream. It was a very well-behaved romance of the time – courteous and adoring. When Otto went to Cuba, their love blossomed through letters which became more intimate and less formal as the years went by. They married on 6 January 1909 and moved to Breslau (Wrocław), one of the biggest Jewish communities in Germany. Their daughters Liese and Edith were born there in 1910 and 1911 respectively.

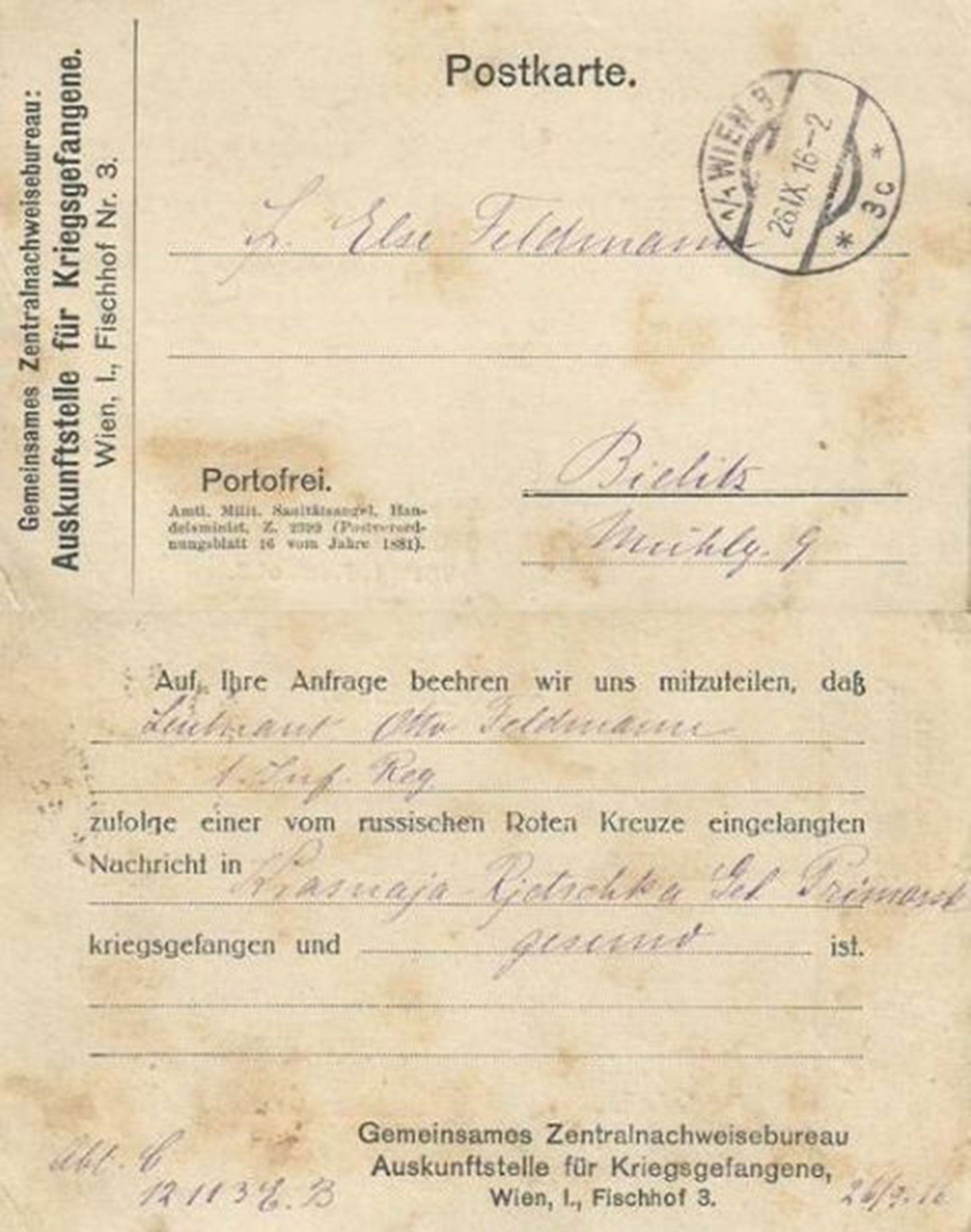

As an Austrian national, Otto joined the Austro-Hungarian Army as an officer upon the outbreak of war in 1914 – thinking, as did millions of others, that the conflict would be over within months. Else returned to live with her mother’s parents in Bielitz – their family owned a large mill which had plenty of room for her and her two daughters. Throughout the war, they stayed at the mill. Else was one of five sisters – two of whom helped look after the children as Else worked to bring in additional income.

Else was pregnant when Otto went to the Eastern Front. Their son Kurt was born in Bielitz on 22 April 1915, and would not meet his father until he was six.

It was Otto’s ability to put his feelings and experiences into “letters she never received”, written in a mathematical notebook which he hid throughout his ordeals, that helped him to survive those terrible years on the Eastern front and in prisoner of war camps.

OTTO’S DIARY: EXCERPTS

First entry, written on 27 February 1915

My beloved little wife! “Letters she never received”! That’s what I call these pages. At last I have reached a decision. Brooding for weeks, my spirit paralysed, I feared that I won’t find the strength to save myself from spiritual death. Last night the redeeming thought came to me; Write to her! She who suffers for you at home, whose thoughts cannot get away from worrying about you, who so often has returned your lost self-confidence to you, she must help you now again. Letters are supremely suitable for this! Surely I need not stress that I am always thinking only of you, and it would be a profanation of my feelings if I wrote these lines just to prove to you that this is so. However, I can in this manner make my thoughts of you more profound and that is my aim. “…she never received” I call these letters because I do not even intend to post them to you. Only when we are happily reunited in our sunny home shall you read them. I have made up my mind to write very diligently: all my feelings, observations, thoughts and perceptions should be contained in this book.

Same diary entry, recalling those first days’ journey to war, Krakow

Thousands and thousands of wagons and carts carrying all sorts of war materials, food supplies, ill and wounded troops were passing us in 3-4 columns while we marched laboriously through sand and clay over the fields. At this occasion I saw for the first time a major casualty; a very young lieutenant of the 10th Dragoon regiment, white like freshly fallen snow, head and arm bandaged, bedded on straw, was driven past us on a peasants cart. I will never forget that sight. It felt as if an ice-cold hand had touched me. At that moment I for the first time fully realized that I was going to war.

Captured in eastern Poland, 21 December 1914 (written later on 3 March 1915)

When crossing the Nieda, we were three times wading through water that reached up to our hips and our clothes were frozen stiff on us. My company was ordered into a second attack that bordered on foolhardiness; almost my whole company remained dead or wounded on the ground and I have only to thank a corporal and a servant for my life. My good Karnovsky twice snatched away the revolver which had already found its way to my temple.

All day through the fighting was ferocious; in the locality behind us every single house was on fire, the dead were lying in heaps together, and exactly at midnight the Russians attacked from three sides and we were captured. I did my duty till the last moment, I fought till the final minute and I have the reassuring feeling that I did everything I could for my Fatherland. Often, while the bullets were whistling around me, I wished for a saving wound. I became aware that I was directly exposing myself so as to “catch one”. I did not know fear, only duty and responsibility. I arrived at the opinion that it was impossible to escape from this witches’ cauldron, that this monstrous war will not release anybody whom it has taken hold of. I always thought of you and the children, also at moments of weakness, and each time when I saw a father fall I wiped off a tear since surely my turn would come soon.

Arriving at Shkotovo POW camp, Siberia, 22 February 1915 (written 15 March 1915)

The surrounding landscape is marvellous. A few hundred steps away we see the expanse of the sea presently still covered by ice. The view of the bay formed by bare, wild, romantic cliffs is unforgettable. However, all this we see only from a distance since we are prisoners. Round our barracks is a high wooden fence, guards with fixed bayonets stand at the gates, we are allowed to go for walks only in this limited space.

Shkotovo POW camp, 28 February 1915

One’s mind has become so numb, one lives just for the food and the hope. We, the dead who have survived by chance. Only two feelings remain strong in me; hope and yearning.

Disease in the camps, 16 March 1915

About 5,000 men are quartered here, Germans, Austrians, Hungarians and Turks, and among these, two cruel diseases have broken out. Typhoid fever and typhus claim numerous victims daily. Is it not the most gruesome fate imaginable to die here in misery after one has been spared by the bullets? How many have been carried out already to the graveyard, there on the hill above the sea. Do not those ill-fated men die a double or triple death? How many, who already confidently hoped to see their loved ones again, are now dying defenceless with a curse on their lips against those who sent them into this misery?

Pining for his wife, 27 March 1915

And now, when the cruel breath of history has separated us by thousands of miles, even if we have to wait for long weeks before we are reunited, I cannot give up the belief that we shall be together again. In the field I have already done my duty in battle, I have many times seen death and met it with defiance, I always valued my duty to my Fatherland higher than my life although I am tied to life by such precious fetters. But God’s will saved me in the rain of bullets. And so I sit here hoping, fearing and pining but always supported by my trust in God. Disease is all around me, there is not space enough any more for all the ailing, any minute I can be thrown down on the hopeless sick bed, feverish fantasies are tearing my brain, but my hope that we shall be reunited will not be destroyed. My love, be brave, I shall thank you for it by my unquenchable love and devotion.

News of the Russian Revolution reaches the camps, 19 March 1917

We live now through the historical days of March. In this unique world war a new shock wave goes through the world: coup d’état, revolution. We are right in the middle of it but we still stand aside. We have a new proof that the wooden fence separates us from the world. We are all inspired by a single thought: will these new events bring the longed-for peace to the world? We hope so. Yesterday, it was a Sunday, much was happening in the town, the prison was taken by storm, the prisoners were freed and meetings were held. A small wave reached even our fence. The crowd came to our fence, many hundreds of people carrying red flags, calling and shouting. The call “Mir” (peace) was frequently heard. Speeches were made, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity were extolled. Yesterday I was a prisoner of the Tsar, today I have become a prisoner of the Russian Republic.

With the Czech legion, homeward, fleeing the Russians, written 16 March 1920

As you know from my sporadic messages from Kansk, I have been working since June 1919 as a pharmacist for the Czech Legion. On 13th January, we left Kansk – the beginning of the evacuation. Very briefly, at first everything went reasonably well, but when we were passing Nizhne-Vdinsk fighting broke out with “the reds” and on 29th January the long wished-for evacuation almost came to a catastrophic end. Nobody, who did not see it with his own eyes, can form a picture of it in his mind. Thousands of men in the cruel Siberian frost, fleeing on foot along the railway track and behind them the vicious enemy. Shortages of water, coal and of good will among the railway personnel brought us often into critical situations. We had to push the train, in the true sense of the word, over distances which were kilometres long, once our engine froze up on the open track, but we got through; when in mid-February a truce was agreed everybody breathed a sigh of relief. I have to survive a hard test of my patience yet, but everything is easy to endure because: I am going home.

In China, 11 April 1920

The arriving train was stormed by Chinese traders. With a lot of noise they were offering silk, cigarettes, fruit, pastries and God knows what else for sale. The whole Manchurian section of the East Siberian railway is presently under Chinese control. Chinese troops occupy the station buildings. We are on neutral ground and have survived the unrest and fighting of Siberia. Immediately after the doctor’s round I went out to see it. New images, new life. What is on offer at the bazaar is simply indescribable. The Chinese are very wily and very crafty. There are 4-5 kinds of currency in circulation here: Siberian, Tsarist (Nikolaevski), Mongolian, Japanese, Chinese and some sub-sorts. Tsarist money commands a high exchange rate and I have 350 roubles Nikolaevski – but more than half of that is “lamajla” (broken), which means it is folded in the middle or in a corner and the Chinese do not accept it. I also have some Siberian money but that is almost worthless. I had to pay 175 roubles for a bath in a tub.

Sailing across the Pacific, from Vladivostok to Vancouver, 14 June 1920

I have been on board the steamship Drotesilans for six days already, and only today am I reaching for my book. After all the delays it is true now: I am travelling home. We are sailing quite near the Bering Strait and close below Alaska. In about 16 hours we shall have done half the distance to Vancouver. Tomorrow or the day after we shall pass the 180-degree meridian where the time difference between the Earth’s east and west half-spheres is compensated for and we must, therefore, count that day and date twice.

Europe in sight, 27 July 1920

Today I have to write to you, however bad the distraction be. This afternoon at 5 o’clock we saw from far away the English coast! Europe!! I had almost despaired of ever reaching it again and now I am here. I am returning to my little wife, to my bride. Within four walls I want to embrace you all for the first time, to hug and kiss you. I was strong enough to withstand the misery of the past six years, now I fear that I am too weak to be able to bear the happiness of the coming days. My little mouse! I am coming!

To read the diary in full, go to ottosdiary.com

AFTER THE WAR

Otto finally returned in August 1920 as a hero, part of the historic Czech Legion’s return to the newly formed country of Czechoslovakia. Family life gradually started again. Otto, Else and their three children moved between Troppau and Bielitz, where Otto found employment for short periods of time. It was hard to make a living in post-war Czechoslovakia, and his brother Hugo helped to support the family.

Otto found a new passion in Zionism – the belief in a homeland for the Jews – and became one of the founders of the HaBoneh movement; a union of engineers and technicians with a vision of aiding the development of a State of Israel in the British mandate of Palestine.

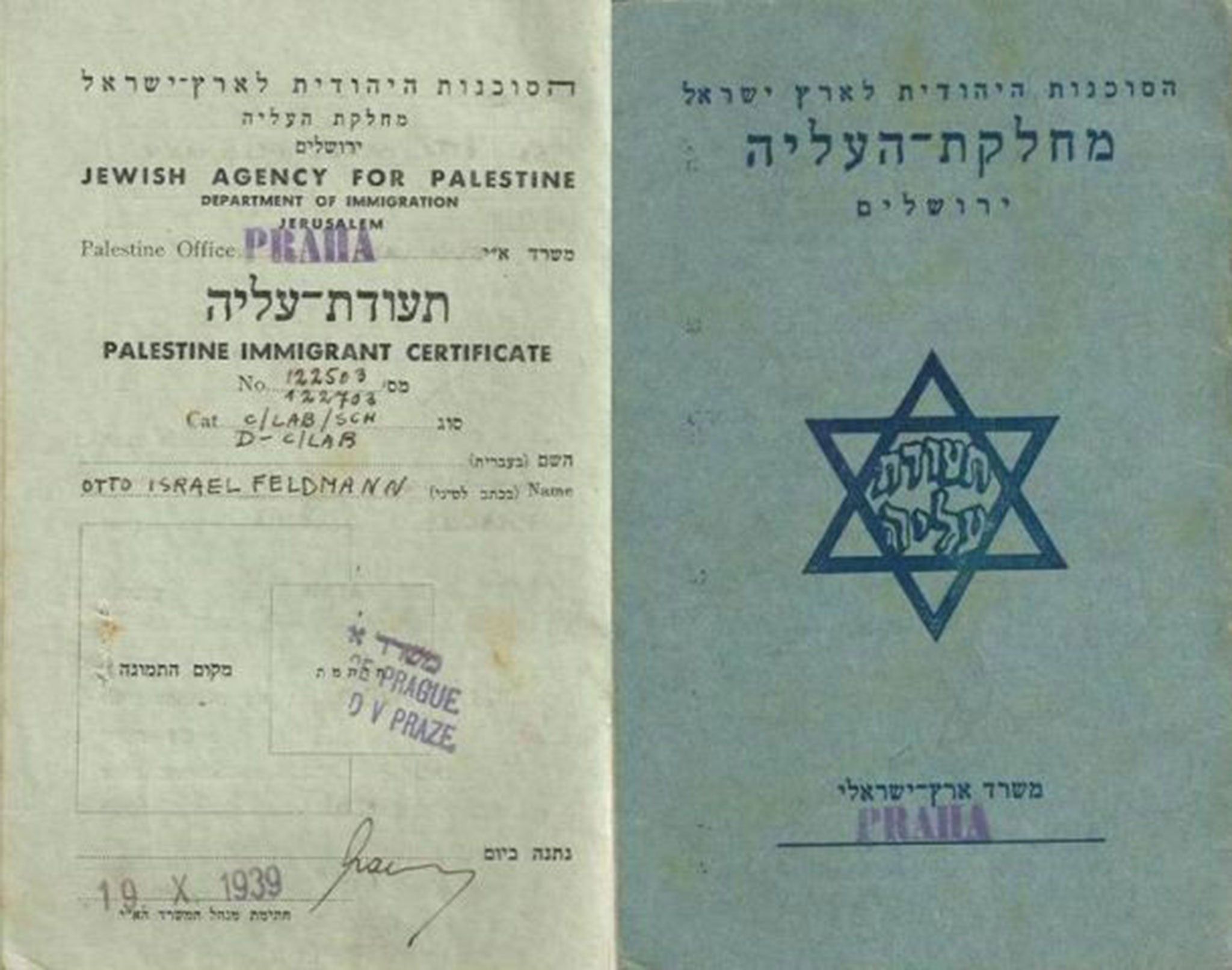

Eventually Otto found secure work with the Brno branch of Gestetner, a pan-European manufacturer of duplicating machines. By transferring Otto to their Tel Aviv office in 1939, the company effectively saved his and Else’s lives – the next six years saw the Holocaust decimate Europe’s Jewish community.

Otto and Else’s youngest daughter, Edith, was as passionate as her father. She became determined to relocate to Palestine as part of the highly idealistic socialist kibbutz movement: fully communal living, no private property or income, full equality for women, and communal care of children. She fought with her parents until they agreed to her let her go in 1933, six years before they eventually followed her. With her pioneering spirit and altruism, she helped to found and build Kibbutz Givat Haim in desert marshland. She married Radius Rath and lived on the kibbutz for the rest of her long life. She died in 2007 at the age of 96. Her family all still live in Israel.

Edith’s son Kurt managed to escape Czechoslovakia just before the outbreak of the Second World War, travelling to England as part of a group of agricultural students. He intended to travel onwards to Palestine to join his sister and parents, but as war swept across Europe this became impossible. He married another Czech refugee, Alice Kohnova, in London in 1942, and spent the rest of his life as a beloved maths teacher for special needs children, and a designer of board games. He died in 2000 at the age of 84. His family remains in England.

Otto and Else’s eldest daughter Liese’s story is very different. Liese and her husband Herbert Langer did not believe in the imminent threat to the Jewish community, even moving closer to Germany for Herbert’s work, with their daughter, Bella-Judith. When war broke out in 1939 the family attempted to escape to Palestine to join Liese’s family, and managed to book sea passage from Trieste. Their belongings arrived at the port ready to be shipped, but the family were captured by the Nazis en route, and were sent to Theresienstadt concentration camp where they perished. Almost all of Otto and Else’s brothers and sisters, and their families, suffered the same fate.

Meanwhile, having moved to Palestine, Otto and Else established a home in Tel Aviv, and Otto remained very active in Zionist movements until the end of his life. There is a memorial to him and his colleagues in a forest outside Jerusalem. When Otto died in 1949, Else moved to Kibbutz Givat Haim to live with Edith and her family. She was always a quiet, home-loving “hausfrau”. But it was from her, and through his love of her, that Otto found his strength. She died on the kibbutz in 1953.

Words by Monica Lanyado (Otto’s granddaughter) and Benji Lanyado (Otto’s great-grandson)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments