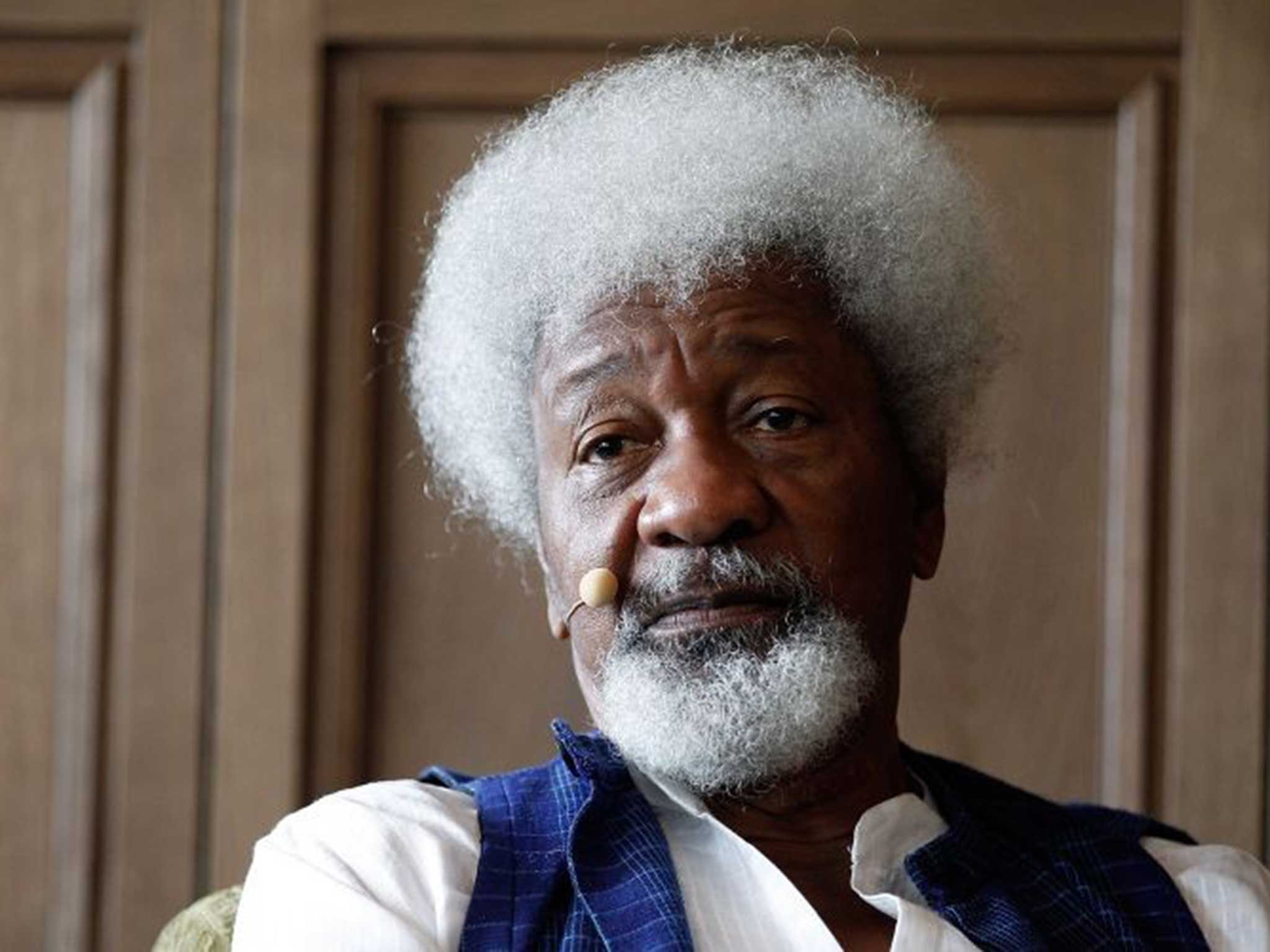

Nobel prize-winning author Wole Soyinka warns of religion's roll call of death

Nigerian says spiritual leaders who fail to confront extremists such as Boko Haram allow fanaticism to thrive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Atrocities carried out by fanatics such as Nigeria's Boko Haram show the dangers of religious belief with the "scroll of faith … indistinguishable from the roll call of death", according to the Nobel prize-winning author Wole Soyinka.

In a video address to the World Humanist Congress, at which he will be presented with its main award today, Soyinka will argue that even moderate religious leaders may be "vicariously liable" for sectarian hatred if they have failed to argue against it.

The actions of the Islamist extremists of Boko Haram – bombing churches, killing civilians and abducting girls – are a warning to the world, Soyinka said.

"The conflict between humanists and religionists has always been one between the torch of enlightenment and the chains of enslavement," said Soyinka. "Those chains are not merely visible, but cruelly palpable. All too often they lead directly to the gallows, beheadings, to death under a hail of stones. In parts of the world today, the scroll of faith is indistinguishable from the roll call of death."

He added that Boko Haram's members considered abducting 200 girls to be "virtuous" and moderate Muslims could not simply disavow their actions with "pious incantations" that "these are not the true followers of the faith". "We have to ask such leadership penitents: 'Were there times when you kept silent while such states of mind, overt or disguised, were seeding fanaticism around you? Are you vicariously liable?'" said Soyinka. "The lesson of Boko Haram is not for any one nation. It is not for the African continent alone. The whole world should wake up to the fact that the menace is borderless, aggressive and unconscionable."

He will be presented with the International Humanist Award at the secular body's annual conference, attended by more than 1,000 delegates from 67 countries.

Boko Haram has been waging a violent campaign since 2009, and has intensified its attacks against civilians this year. More than 4,000 people – mostly civilians – have been killed this year alone "by all sides" of the conflict, including in counter-attacks of security forces against the group, according to Amnesty International. This compares with an estimated 3,600 people killed in the first four years of the insurgency.

Elsewhere in the world, it is feared the Islamist militants of Isis (now Islamic State) may be about to carry out the genocide of Christians and tens of thousands of members of the Yazidi belief hiding on a mountain in northern Iraq. And in Burma, some 140,000 Muslims of the Rohingya ethnic group, one of the world's most persecuted religious minorities, are trapped and starving in camps after being chased from their homes by Buddhist mobs who killed up to 280 people.

Andrew Copson, chief executive of the British Humanist Association, said the award had been given to Soyinka in recognition of his "brave advocacy for free expression, even under extreme threats to his life".

The writer narrowly escaped a death sentence in Nigeria in 1994 when he was charged with treason by late Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha. Tipped off he was about to be arrested, Soyinka fled the country.

"Freedom of expression is a right. But it sometimes takes deep personal courage to stay true to its promises in the face of powerful religious 'sensitivities'," said Mr Copson. "We all have much to learn from Wole."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments