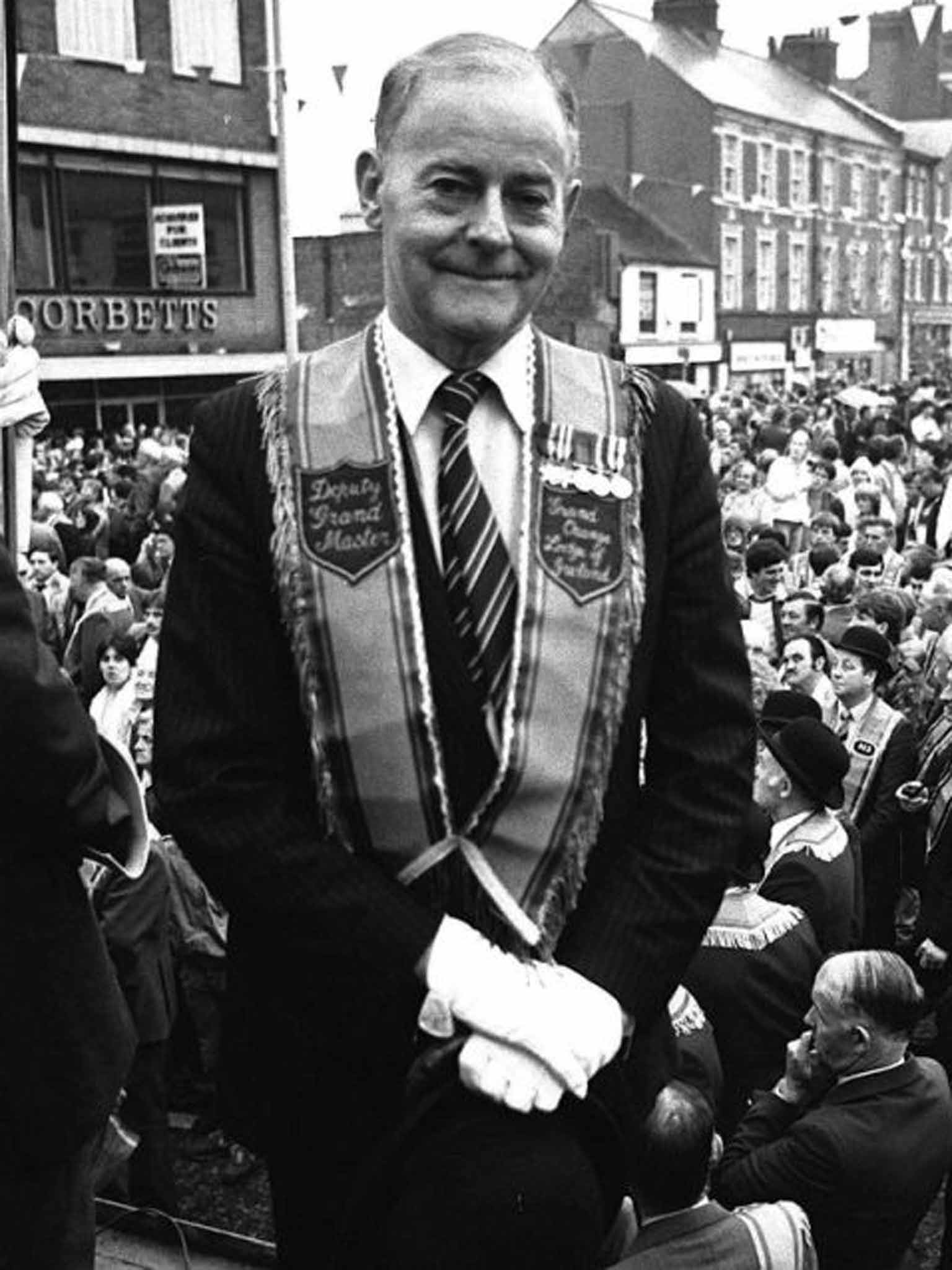

James Molyneaux: Ulster Unionist leader for 16 years who fought an ultimately losing battle to maintain the status quo

A leader of the Orange Order and associated organisations for almost half a century, he was never known as a bigot or as aggressive in his Protestantism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.James Molyneaux was so self-effacing that, although he led Northern Ireland's largest political party for much of the Troubles, he remained virtually unknown to the wider British public. As leader of the Ulster Unionist party between 1979 and 1995 he might have been expected to be in the limelight. Instead he shunned publicity and prominence, preferring to operate in the shadows and mostly avoiding TV appearances.

When he was described as the dull dog of politics, his reaction was not one of offence but of delight. He took pride in the long view – the title of his biography – and frowned on "high-wire initiatives." Where his perennial rival, the Reverend Ian Paisley, was often raucous, he was unfailingly courteous, the most low-key of politicians and as colourless as Paisley was colourful.

What he had in common with Paisley – at least until the latter's entente cordiale with the former leaders of the IRA – was that he was simply not in the business of making a deal with Irish nationalists. His belief, unshaken over the decades, was that the Unionist cause was best served by a defensive posture aimed at preserving the status quo.

He once compared himself to "a general with an army that isn't making anything much in terms of territorial gains but has the satisfaction of repulsing all attacks on the citadel." He was the embodiment of the siege mentality, the master of the dead bat, the Geoffrey Boycott of Unionism.

But his lifelong devotion to the politics of suffocation was in the end markedly unsuccessful as he watched first the advancement of Anglo-Irish relations and, later, the growth of Irish republicanism as a political force. To his successor, David Trimble, Molyneaux gave nothing but trouble, opposing the idea of negotiating with opponents and encouraging the anti-Trimble factions in their various heaves against him. But if Molyneaux arguably failed in many of his aims, he did succeed in holding Paisley at bay electorally during his term of leadership. Outsiders might criticise him as uninspiring but he held considerable appeal for Ulster Protestant voters.

James Henry Molyneaux was born in 1920, the son of a poultry farmer at Crumlin, Co Antrim, not far from Belfast. He left school at the age of 15, helping on the farm before joining the RAF in 1941. He landed in France on D-day as a leading aircraftsman.

He arrived at Belsen concentration camp three days after its liberation, where he saw sights which gave him nightmares for years afterwards. "My first encounter with Belsen was the sight of dead bodies hanging from the electric fences," he recalled. "These victims had thrown themselves on the fences to end their own unimaginable suffering."

After the war he joined his uncle's printing business before, by his own account, drifting into politics and serving 24 years as a grassroots toiler before he reached Westminster. There he represented South Antrim for 13 years and Lagan Valley for 14. The story goes that before one election a Tory backbencher asked Molyneaux the size of his majority, and was told "38." The Tory, thinking the constituency was a marginal, replied: "Oh well, fingers crossed, eh?" Molyneaux explained that he meant 38,000, the largest majority in the Commons.

Although he was a leader of the Orange Order and associated organisations for almost half a century, he was never known as a bigot or as aggressive in his Protestantism. But he was utterly unyielding in his politics, as immovable as he was courteous. He ascended slowly but inexorably in the Ulster Unionist hierarchy, becoming leader in 1979 after his predecessor Harry West had been humiliated in an election by Paisley. Molyneaux managed to staunch the flow of votes to Paisley while increasing the sense of party unity.

It was an open secret that he was an integrationist rather than a devolutionist, meaning that he preferred Northern Ireland to be ruled directly from Westminster rather than through a subordinate assembly in Belfast. But his party contained a strong devolutionist wing, which Molyneaux dealt with through obfuscation rather than confrontation. He seemed to set out to baffle Unionist audiences, his biographer Ann Purdy admitting: "The portrayal is always of someone who speaks in gobbledegook."

He formed a close alliance with Enoch Powell, who as a Unionist MP was another convinced integrationist. One-time Northern Ireland Secretary Jim Prior wrote in his memoirs: "At Westminster he was Enoch's puppet, and it made him a less pleasant man than his nature would normally have dictated."

Molyneaux's reaction to the efforts of Prior and others to talk him into devolution was one of polite but firm immobility. "He remains inert," a British official complained after yet another futile round of talks.

Molyneaux's own proposals, which appeared more as an alibi than a policy, centred on esoteric parliamentary adjustments such as a new Commons select committee on Northern Ireland. His weakness was that this did not begin to address the vital questions of the mid-1980s: how to improve relations with Dublin, deal with northern Catholic alienation and tackle the menace of a growing Sinn Fein and an ever-dangerous IRA.

Although he and Powell were convinced they had the ear of Margaret Thatcher, they suffered a spectacular setback in 1985. Molyneaux had convinced himself that Thatcher was unattracted by Anglo-Irishry, declaring: "She is far too realistic to be fooled by any of that stuff." But the British and Irish governments signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement to signal a new era of London-Dublin cooperation. Unionists regarded the Agreement as a betrayal but it continued to form the template for Anglo-Irish relations. Some of their protests led to disorder which was condemned by Molyneaux, who throughout his career was implacable in his opposition to violence.

He stayed on as Ulster Unionist leader, even though his reputation as the man with the inside track took a severe battering. Later he staged a partial recovery: he was thought to have done well in 1979 in winning concessions from a weak Callaghan government, and a similar situation seemed to have developed during John Major's last year in office. He continued to hold off the electoral challenge from Paisley, who after years of co-operating with him suddenly denounced him as "Judas Iscariot." It was a denunciation too far, rebounding on Paisley and doing Molyneaux little harm.

Yet after a decade and a half the politics of inertia and non-engagement had had their day: some wanted a more aggressive line, others favoured talks. Then things changed utterly with the IRA ceasefire of 1994. Molyneaux and most Unionist leaders were strongly opposed to the entire peace process: when John Hume entered talks with Gerry Adams of Sinn Fein, Molyneaux said he had "sold his soul to the devil."

Realising that inertia would be increasingly hard to maintain in the face of such extraordinary events, Molyneaux said of the ceasefire: "It started destabilising the whole population in Northern Ireland. It was not an occasion for celebration, quite the opposite." It certainly destabilised his own position, as did a "stalking-horse" candidate who stood against him in a leadership contest and registered ominously substantial support. The loss of a Westminster by-election hastened his departure in 1995.

The action of his successor, David Trimble, in negotiating with all sides, including Sinn Fein, represented a dramatic departure from the Molyneaux line. Trimble believed that the new republican approach could not simply be met with what he called the "stone face." He declared: "It is not good enough to be passive, to adopt an approach that consciously leaves the decision in the hands of other people."

Trimble's policy of engagement won him international plaudits, including a Nobel Peace prize, but Paisley triumphed in a general election and Trimble resigned as leader. Molyneaux might have pointed out that the party he bequeathed to Trimble was in reasonable shape but was decimated within a decade. Trimble might retort that the Molyneaux sit-tight approach could never have held out against the combination of new Labour and new republicanism.

James Molyneaux was admitted to the Privy Council in 1983. He was knighted in 1996 and given a life peerage in 1997. He never married.

James Henry Molyneaux, politician: born County Antrim 27 August 1920; Kt 1996, cr. life peer 1997; died 9 March 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments