Dowager Duchess of Devonshire: The youngest Mitford sister, an acclaimed writer and the successful head of Chatsworth House

She was a positive figure with a no-nonsense outlook, a great anti-melancholic and life force for friends or employees in difficulty

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Deborah Devonshire was the last of the celebrated Mitford sisters and became a literary figure – as historian, memoirist and magazine diarist – just as compelling and idiosyncratic as her elder siblings, the novelist and historian Nancy Mitford and the campaigning journalist Jessica Treuhaft.

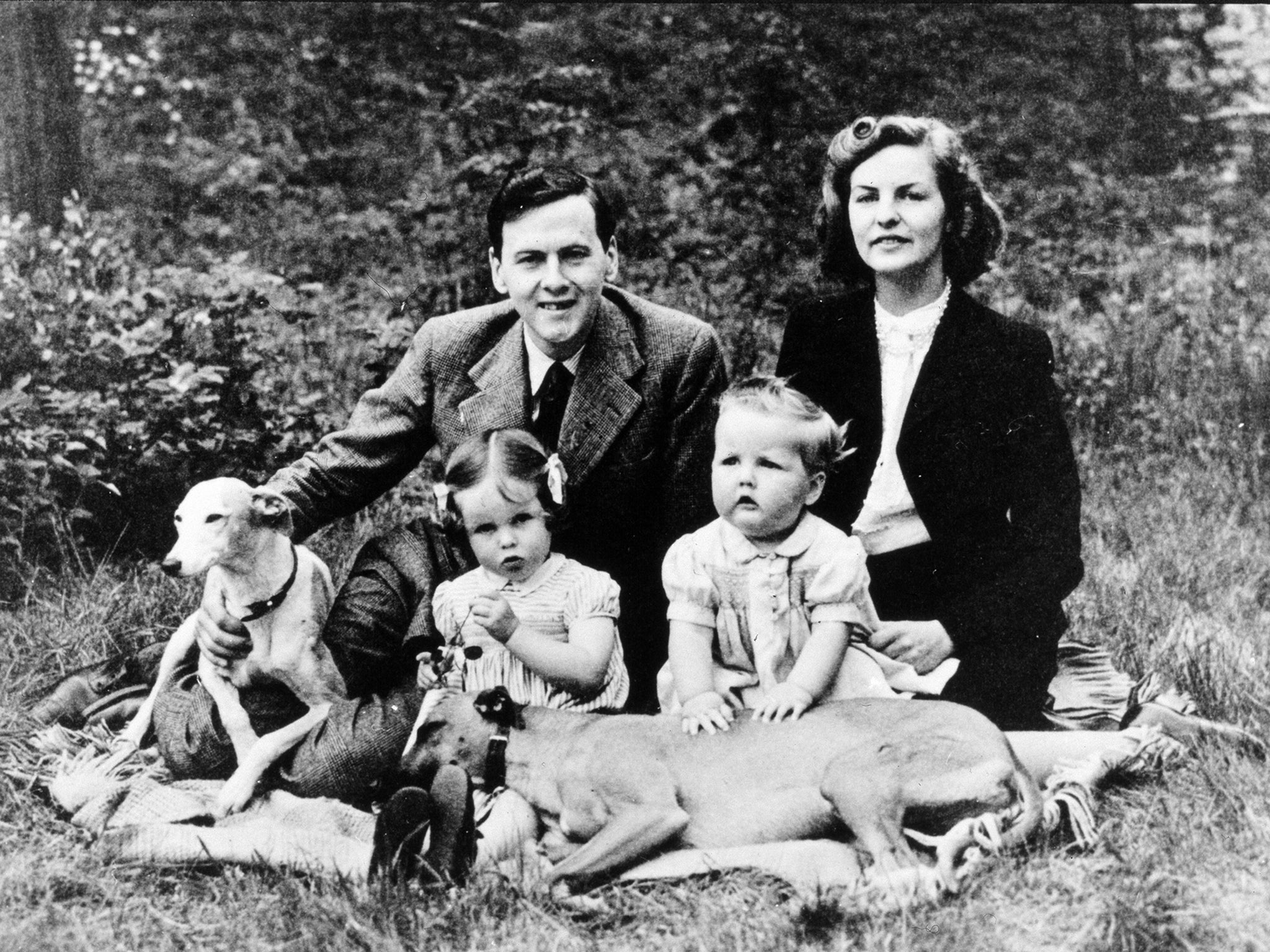

With her husband, Andrew Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire, “Debo” Devonshire – she barely pronounced that final vowel, making it closer to “ou” or “eu” than “oh” – brought Chatsworth in Derbyshire, the splendid Palace of the Peaks, with its matchless contents and late 17th-century interiors, back to life in the 1960s. In the postwar years of austerity, with rationing of materials and building permits, and huge death duties, many people felt that the house, which had been home to a girls’ school in wartime, might never be lived in again.

The Devonshires’ decision to move the family back into Chatsworth in 1959 – they were parents to a son, Peregrine (now the 12th Duke of Devonshire), and two daughters, Emma Tennant and Sophy Topley – was a bold statement at a time when, as the duchess recalled, “the country house” was, for political as much as cultural reasons, a “dirty word”. It was the first grand gesture in a trend that made enjoyment of Britain’s built heritage one of the great cultural phenomena of the late 20th century.

By the time Debo entered the family writing trade – her father David Mitford, 2nd Lord Redesdale, had been general manager of The Lady, a magazine founded by his father-in-law – with The House (1982), a scholarly but deftly amusing history of Chatsworth, the Mitford family legend had been well established. Nancy’s novels The Pursuit of Love (1945) and Love in a Cold Climate (1947) were thinly veiled accounts of the characterful, not to say eccentric upbringing enjoyed by the children of David and his wife, Sydney Bowles. And Jessica’s memoir Hons and Rebels (1960) confirmed just how closely Nancy’s character Uncle Matthew was modelled on the Mitfords’ beloved if mildly terrifying “Farve”.

Lord Redesdale’s expertise in country pursuits made Debo’s Oxfordshire childhood – first at Asthall Manor, near Burford, and then at Swinbrook House (built by Lord Redesdale to his own design), across the Windrush valley – an enthralling, heady thrill in itself and a solid education for life as chatelaine of Chatsworth and the other Cavendish family estates at Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire, and Lismore Castle, Co Waterford. The BBC documentary Nancy Mitford: A Portrait by Her Sisters (1980) cemented the family legend and revealed what a television natural the Duchess was. Asked about the “Mitford voice” – a halting, clipped bon ton delivery exaggerated even for their class and generation – she said: “We are saddled with it, aren’t we? It’s awful. Living in the North of England it’s even sillier than it is living anywhere else.”

In the film she perpetuated the myth of her unbookishness: “Nancy always said ... that I was the mental age of nine. She’d got a point, I’m afraid, and she always said I couldn’t read… Well I hardly can read… I hate it, hate books.” Whatever the truth – Evelyn Waugh once gave her a copy of his biography of Mgr Ronald Knox with all the pages blank – it makes it all the more remarkable that she came to be a writer as vivid and memorable as Nancy. The House dragged the dusty “country house book” genre out of the literary backwaters with its crisply readable mix of compelling anecdote and memorable characters.

By then she had proved herself a formidable businesswoman, resurrecting the glories of Chatsworth, establishing a standard-setting country house shop in the sculpture gallery. The Chatsworth nick-nacks for sale (trays, stationery and China), and its moveable Gothick cabinets, were better looking than anyone else’s. The house shop had many imitators, as did the farm shop with its eggs laid by the duchess’s rare breed hens. Her son-in-law Toby Tennant gave her a desktop sign bearing the legend “The Boss”.

The House was just the beginning of a formidable output of journalism – her essay on bringing a goat by train to London in wartime from her parents island home in Scotland is a classic worthy of comparison with the best of PG Wodehouse or Saki – and books, centred on Chatsworth, country matters (an accomplished dog-handler, she made guest appearances on One Man and his Dog) and the Mitford family. She was the assiduous keeper of the Mitford archive, a trove of correspondence relating not just to Nancy and Jessica but also to their brother Tom and sisters Pamela Jackson, Diana Mosley, wife of Sir Oswald Mosley, and Unity Mitford, whose notorious friendship with Adolf Hitler led her to attempt suicide in Germany.

Nothing in the archive could be more sparkling or effortless than Debo’s letters: pithy, to the point and engaging. They were a reminder for her friends of what it was like to see her – intelligent blue eyes alert, a smile, and the promise of laughter, and teasing, to follow. They were the embodiment of her positive and no-nonsense outlook – she was a great anti-melancholic and life force for friends or employees in difficulty – and her teasing delight in the eccentricities of her friends and family.

She extended the Mitford taste for nicknames – Nancy was “Lady”; Pam “Woman”; Diana “Honks”; Unity “Birdie”; Jessica “Hen”; Debo “Hen” or “Stublow” – to her family and friends. Her husband Andrew was “Claud” (when styled Lord Hartington, he sometimes received letters addressed to “Claud Hartington”); her son Peregrine “Stoker” or “Sto”; her daughter Emma “Marlborough” and her daughter Sophy “Moffa”. The pioneering conservationist Sir John Smith was “Deity”, the architect Philip Jebb “Perfect” or “Dear Good”, the decorator John Fowler “Simon” (a corruption of a builder’s moulding called Cyma Reverso) and her great friend Kitty Mersey “Wife” or “My Wife”, a play on how Lord Mersey referred to her as “Kitty-my-wife”, as if it were all one syllable.

The outside world got a first taste of her quality as a correspondent in The Mitfords: Letters between six sisters (2007), edited by Charlotte Mosley, Diana’s daughter-in-law. It also revealed some of the more complex eddies in the affections and tensions between the sisters, not least the long estrangement between the socialist Jessica and the fascist Diana. Debo did not share her sisters’ views; many thought that their open fanaticism had immunised her into being apolitical for life.

In her memoir Wait for Me! (2010) her parents emerge as more rounded, complex human beings than in her sisters’ memoirs. The section on her birth is classic Debo: “Blank. There is no entry in my mother’s engagement book for 31 March 1920, the day I was born. The next few days are also blank. The first entry in April, in large letters, is ‘KITCHEN CHIMNEY SWEPT’. My parents’ dearest wish was for a big family of boys; a sixth girl was not worth recording… Nancy wrote to Muv... ‘How disgusting of the poor darling to go and be a girl.’ ”

In Wait for Me! she gives vivid accounts of the tremendous ups in her life, and the great friendships (Lucian Freud; John F Kennedy, whose sister Kathleen had been married to Andrew Devonshire’s elder brother William; Alan Bennett), but is unsparing about the great lows, too. Three of her six children – Mark, Victor and Mary – died on the day they were born. Her husband’s struggles with alcohol forced her to leave home and give him an ultimatum: stop drinking or she would not return.

Andrew stopped drinking, Debo returned home and they resumed their lives as masters of a happy, thriving estate at Chatsworth, where the food was good, the company was witty and good manners shown and expected (woe betide the young man slow to offer a seat or open a door for a lady). Great balls were held, when Debo would happily do “full duchess”, dressed up in the “family fender”, the Devonshire tiara, parure and stomacher.

After Andrew’s death in 2004 Devonshire moved into the old vicarage in the estate village of Edensor and kept up her busy life as author, correspondent, grandmother and great-grandmother (aided by her brilliant secretary and research assistant, Helen Marchant) until first her eyes began to fail and then, cruelly, she began to lose her memory – the source of her great and indelible output as writer, materfamilias and friend.

Deborah Vivien Freeman-Mitford, writer and businesswoman: born London 31 March 1920; married 1941 Lord Andrew Cavendish (succeeded 1950 as 11th Duke of Devonshire; died 2004; one son, two daughters, and two sons and one daughter deceased); died 24 September 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments