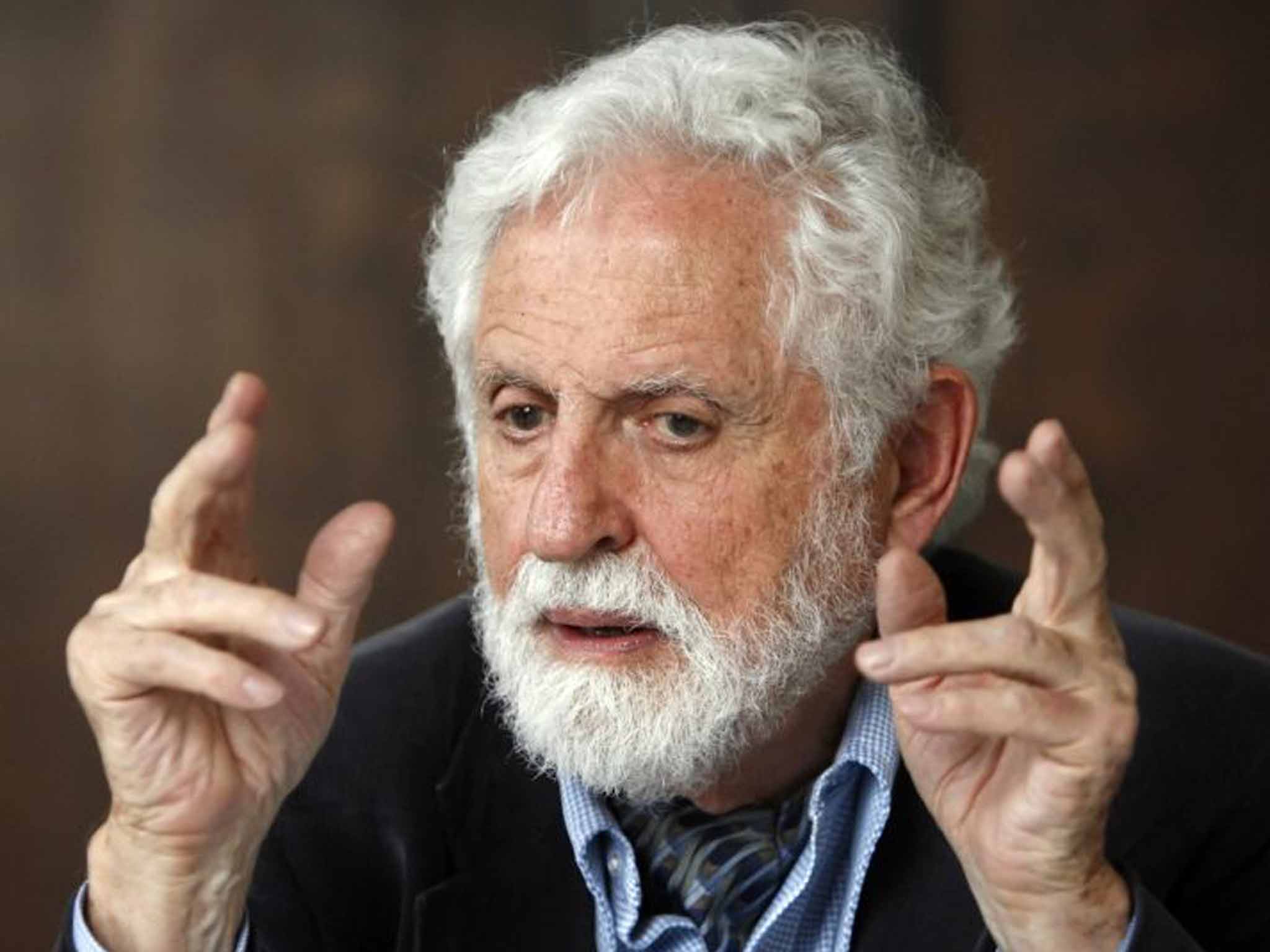

Carl Djerassi: Chemist hailed as 'the father of the Pill' whose work helped pave the way for the sexual revolution

He said that one sure effect of the Pill was fewer unwanted pregnancies and abortions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Carl Djerassi provided the chemistry behind the sexual revolution by patenting the synthetic hormone used in the Pill. An Austrian-born research chemist, Djerassi crossed academic disciplines to study how the birth-control pill he helped create influenced women's health, gender equality and global population. "By separating the coital act from contraception, the Pill started one of the most monumental movements in recent times, the gradual divorce of sex from reproduction," he wrote in This Man's Pill: Reflections on the 50th Birthday of the Pill (2001), the last of three autobiographies.

As a professor at Stanford University he explored the human side of science, and the moral conflicts scientists face, in novels, non-fiction books, plays and short stories. He took issue with the epithet "Father of the Pill", saying that it excluded others such as the biologist Gregory Pincus and the obstetrician and gynaecologist John Rock, who played key roles in the long path toward an oral contraceptive.

In 1951, as associate director of chemical research at Syntex SA in Mexico City, Djerassi led work on a synthetic version of progesterone, the hormone involved in pregnancy and menstruation. Using diosgenin, a chemical abundant in Mexican yams, the team created a contraceptive steroid that could be taken orally. The drug, norethindrone, was successfully synthesised on 15 October 1951 and patented by Djerassi along with his Syntex colleagues George Rosenkranz, the chief chemist who would rise to chairman, and Luis Miramontes, a doctoral student in their lab.

In fact Enovid (Conovid in the UK) was the birth-control pill first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, in 1960, developed not by Djerassi but by Frank Colton at GD Searle. Djerassi's version was also soon approved and became an industry standard. Syntex then introduced its own pill, Norinyl.

In Britain, in October 1961, on the recommendation of the Council for the Investigation of Fertility Control which it had set up, the Family Planning Association added Conovid to its approved list of contraceptives. And on 4 December 1961 Enoch Powell, then Minister of Health, announced that Conovid could be prescribed through the NHS at a subsidised price of two shillings a month.

By 1965, seven US companies were marketing versions of the Pill, with sales reaching $65m. Syntex was then the most heavily traded company on the US Stock Exchange, supplying the basic compound for its own version and for those made by other companies. Syntex was bought in 1994 by the Swiss company Roche.

Starting with a 1969 piece for Science magazine on the global implications of contraceptive research, Djerassi waded into the public-policy debate spawned in part by his creation. Hippie culture, rock'n'roll and women's liberation would have triggered a sexual revolution even if the birth-control pill didn't exist, he believed. But one sure effect of the Pill, he said, was fewer unwanted pregnancies and abortions. "No one expected that women would accept oral contraceptives in the manner in which they did in the '60s," he later recalled. "The explosion was much faster than anyone expected."

He also noted how the Pill had partly worked against women's best interests. "Modern, intelligent men won't take responsibility, wouldn't even use condoms," he said. "They shrugged and said, 'All women are now on the Pill, I don't need to bother.' This has become another woman's burden." Meanwhile, his role in creating the contraceptive, he wrote in his 2003 autobiography, turned him "from a 'hard' physical scientist to a much 'softer' chemist concerned with the deeper social ramifications of my work."

He was born in Vienna in 1923 to two Jewish doctors, Bulgarian-born Samuel Djerassi, who specialised in venereal diseases, and the former Alice Friedmann, a dentist. They divorced when he was young. Fleeing the Nazis in the late 1930s, Djerassi and his mother settled in New York with little money. He graduated from Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, with a degree in organic chemistry in 1942. While working as a research chemist at Ciba Pharmaceuticals in New Jersey he began graduate studies at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, today's Polytechnic Institute of New York University and in 1945 he received a PhD from the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

He spent four more years with Ciba, researching steroids, before joining Syntex in Mexico City, where, in addition to norethindrone, he worked on synthesising cortisone. He returned to the US in 1952 to teach in Detroit while continuing his association with Syntex. From 1959-2002 he was a professor at Stanford, where he designed an undergraduate course, "Biosocial Aspects of Birth Control" and a graduate writing course on biomedical ethics.

He won the US National Medal of Science in 1973 for his work on the Pill and the National Medal of Technology in 1991 for his leadership at Zoecon, a developer of environmentally friendly insect control products. He was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame in 1978 for research that led to antihistamines and anti-inflammatory drugs, in addition to oral contraceptives.

Perhaps fittingly for a man associated with the sexual revolution, Djerassi was open about his own turbulent love life. While married to his first wife, the former Virginia Jeremiah, he had an affair that resulted in the pregnancy of the woman who became his second wife, Norma Lundholm. He later acknowledged it was "ironic" that he had contributed to an accidental pregnancy, which he attributed to failure of a condom. He had a vasectomy in his 50s.

That pregnancy produced a daughter, Pamela Djerassi Bush, an artist who committed suicide in 1978, aged 28. In her honour her parents founded the Djerassi Resident Artists Program, an artists' retreat near Woodside, California.

Dale Djerassi, his son by his second wife, is a filmmaker. His third wife, Diane Middlebrook, a biographer and English professor at Stanford, died in 2007.

Carl Djerassi, chemist: born Vienna 29 October 1923; married firstly Virginia Jeremiah (marriage dissolved), secondly Norma Lundholm (marriage dissolved; one son, and one daughter deceased), thirdly Diane Middlebrook (died 2007); died San Francisco 30 January 2015.

© Bloomberg News

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments