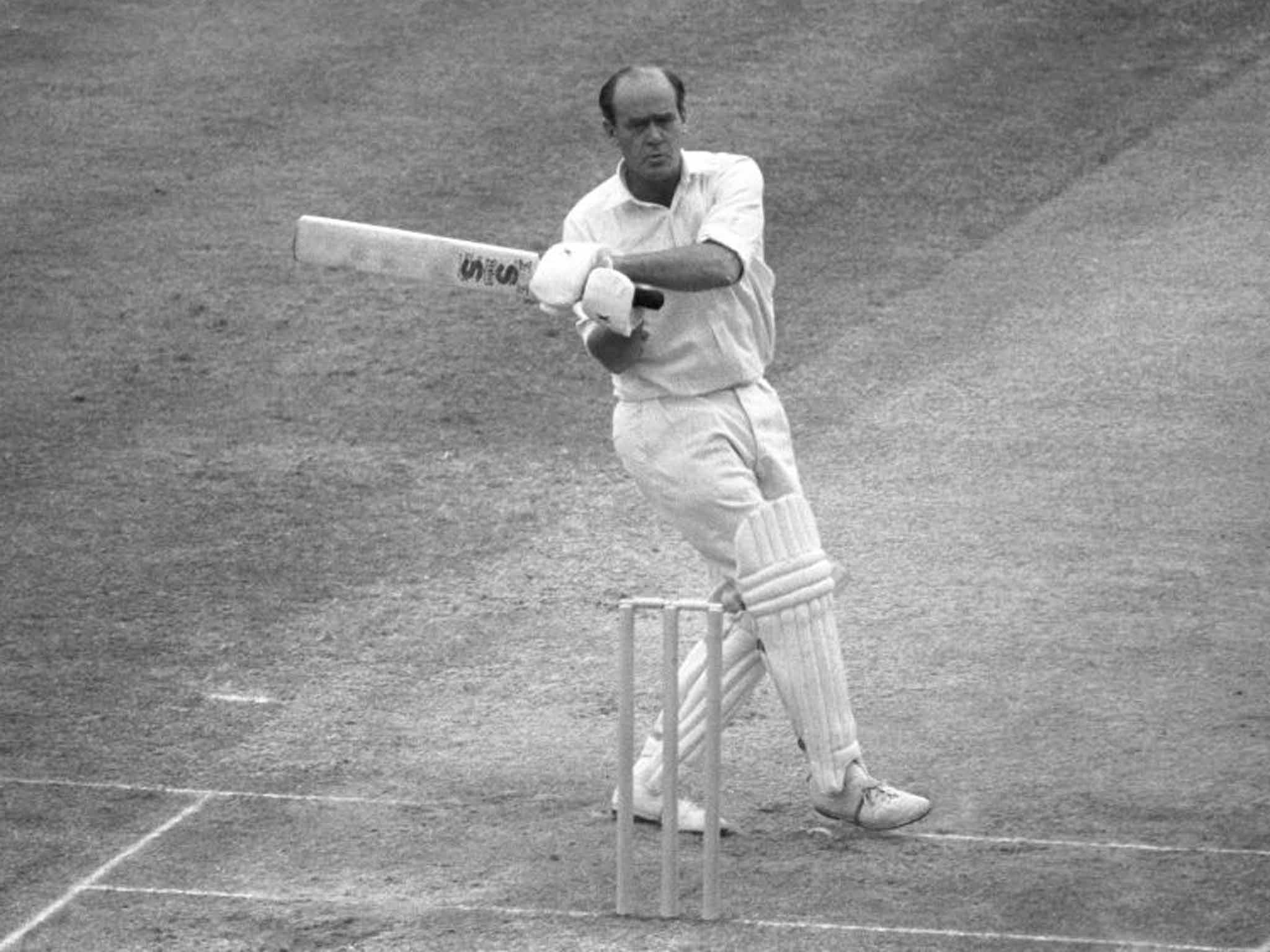

Brian Close: Cricketer whose courage and skill with bat and ball were matched by a ferocious and inspirational will to win

He was also a good enough footballer to play professionally, as a striker, for Leeds United, Arsenal and Bradford City

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There have been few players in the history of cricket who have been blessed with more natural talents than Brian Close. As a left-handed batsman he was capable of defending or attacking on the uncovered pitches of the two postwar decades, against bowling of the highest class. His hitting could be phenomenal. As a bowler he could deliver right-arm seam-up and then switch to off-spin.

As a close-in fielder his renown echoes down the years; tales of his catches are still told on the circuit. Add to all this an unquenchable thirst for victory and a total disbelief in defeat.

In later years he developed into an outstanding captain, a motivator and wily gambler, and above all a man who led from the front. Close did not ask any man to do what he was not prepared to do; he did what all but very few of his players were brave enough to try. "The toughest man I ever played with or against," said Ian Botham. Close was probably the only player to have even more confidence in his own ability than his protégé.

He came from a family steeped in Bradford League cricket and by the age of 11 he was playing for Rawdon's first XI. He was also a good enough footballer to attract attention and went on to play professionally, as a striker, for Leeds United, Arsenal and Bradford City before a knee injury confirmed the direction of his career.

His cricket developed at Hedley Verity's school, Aireborough Grammar, and he appeared for the Guiseley and Yeadon clubs and, on his first appearance at the Headingley Shed in the winter of 1948-49 he was mentioned by Bill Bowes as " a natural successor to Frank Smailes", an all-rounder who had played for England two years previously. He was one of nine young cricketers who went on to play first-class cricket from that year, four of them (Frank Lowson, Fred Trueman and Ray Illingworth were the others) winning England caps.

Close, Lowson and Trueman all went on to make their county debuts at Fenner's the following spring against Cambridge University and this watching National Serviceman recorded Trueman as "fast but erratic", Lowson "frail looking and unlikely to survive" and Close as "the most mature, a definite prospect". Such hubris apart, I was right about Close.

Tall and well-muscled, by mid-season he had scored 579 runs and taken 67 wickets; he played in a Test trial, top-scored (65) for the Players against the Gentleman and was chosen, England's youngest selection at 18 years and 149 days, for the third Test against New Zealand at Old Trafford. Ordered to chase runs, he was caught at long on for a duck; his bowling figures were 1-85. Nevertherless he went on to complete the double – 1,098 runs and 113 wickets – in his first season, a prodigious achievement.

He was then called into the Army and played only one first class match for Yorkshire the following summer but was still selected for Freddie Brown's 1950-51 tour of Australasia, a journey that proved to be an intense disappointment, for himself and for England. He may not have been fully fit for first-class cricket and was twice injured.

He found little sympathy among the senior players and came back thoroughly disillusioned with what he regarded as the England establishment. He was probably regarded, in the hierarchical order of the dressing room, as "too big for his boots".

Returning to county cricket in 1952 he did the double again, but another football injury, playing for Bradford City, ended his dual career. Close thought his bowling career was over and was playing purely as a batsman when, in 1954, Bob Appleyard's brilliant career appeared to be coming to an end (he was finally to retire in 1958). Close, ever confident and willing, tested his knee and took up seam and spin again and finished that season with 66 wickets.

By 1955, six years after his astonishing start, he was fully into his stride, an outstanding all-round cricketer yet still regarded as something of an enfant terrible. He fielded so near to the crease that his very presence induced a nervous state in the batsman. Close once stood at silly point, blood gushing down his boot from a shin gash, blasting the bowler for the delay in returning to his mark while team-mates, aghast, were expecting him to keel over.

His lust for victory was magnified by his election as Yorkshire's captain in 1963. Mike Brearley wrote: "He, of all the captains I have known, led from the front. His courage was notorious. Fielding incredibly close in at short square leg (helmets were then unknown), the great dome of his head thrust belligerently forward, he was regularly struck by the ball. "The story went that it once rebounded from his forehead to second slip. 'Catch it,' Close yelled. The catch was completed so he then assured his alarmed colleagues that he was all right. 'But what if it had hit you an inch lower?' someone asked. 'He'd 'ave been caught in't gully'."

In his seven years as Yorkshire's captain he won four Championships and two Gillette Cups. Don Mosey described his style: "His side of the Sixties, though occasionally exasperated when he went off on one of his mental walkabouts, sometimes moved to laughter at his fixations, nevertheless regarded him in affectionate wonderment and professional respect.

"As a captain in the field he had above all, flair. He would bring about a bowling change or switch a fielding position when there was absolutely no reason for doing so; nine times out of 10 it came off. He was an implicit believer in his ability to make something happen when nothing seemed likely".

Another legend involves Yorkshire's being entertained aboard HMS Victory at Portsmouth. The Navy's hospitality was prodigious – "few could have walked the plank without falling off" was one account – and tall tales were told, including feats of climbing the main-mast in bad weather. Close, challenged and more than merry, marched out and climbed it in pitch darkness.

England's selectors tended to keep him at arm's length. His attempt to blast Richie Benaud out of Australia's attack in 1961 was deemed ill-judged but two years later Close impressed himself on the nation when he took a barrage of bouncers from the fast West Indians Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith on his body at Lord's, almost winning the Test. The next day a famous picture showed his torso to be dotted with ugly purple bruises. That same day (no resting between Tests then) he bowled 25 overs against Glamorgan, taking 6 for 55 and went on to score 61 and take another 4 for 19 to ensure a Yorkshire win.

His success as Yorkshire's captain inevitably brought him more national attention and in 1966, with West Indies leading 3-0, Close replaced Colin Cowdrey as captain for the last Test, at the Oval. He went on to win six and draw one of the next seven Tests, including series against India and Pakistan, but it was no secret that the selectors were having collywobbles at the thought of his leading England into the cauldron of cricket and politics in the West Indies. Close's friends believe there was a plot; the establishment insists the allegation to be paranoid.

The following summer Yorkshire needed to win at Edgbaston to displace Kent as leaders but Warwickshire, needing 142 to win in 102 minutes, looked likely victors. The innings was interrupted by rain and the over rate, for various reasons, declined to six in the last 30 minutes; the crowd believed that Yorkshire were deliberately wasting time.

The match was drawn, the crowd became incensed, Fred Trueman was reported to have been attacked with an umbrella, Yorkshire players' cars were damaged and Close was accused in a Sunday newspaper of attacking a spectator. That allegation was proved to be unfounded but the Yorkshire captain was censured by the Board and lost the England captaincy, and the mandatory 20-over rule in the last hour was introduced for Championship matches.

Close continued to lead Yorkshire successfully to the end of the decade but made no secret of his contempt for one-day cricket, and would have agreed with Neville Cardus that it was like "playing Beethoven on a banjo". He was also criticised inside the county for his reluctance to introduce younger players.

The climax came in 1970 when the Cricket chairman Brian Sellers told Close he had been sacked. The iron man confessed that, on his drive home, he had to stop the car. He was weeping.

His ability and reputation was such that there was no lack of offers. While Yorkshire, under their new captain, Geoffrey Boycott, trailed off towards 20 years in the wilderness, Close arrived in Taunton, where he injected so much self-belief into a sleepy Somerset side that they have remained contenders to this day. They still tell the tale of the young Somerset batsman who was so scared of facing the captain's wrath, having been dismissed playing the shot he had been specifically warned against, that rather than walk back into the pavilion he edged his way around the back and climbed into the dressing room through a window.

Close turned Somerset into formidable competitors, and at the age of 45 was recalled to face a new generation of West Indian fast bowlers, Michael Holding and Andy Roberts, with the same obduracy and courage as before. Yet he played in only 22 Tests in a 28-year career.

Close returned to Yorkshire on his retirement in 1977 and was a leader of the anti-Boycott forces during the county's civil war while serving the Committee. He was awarded a CBE for his services to cricket, played his last first-class match at Scarborough at the age of 55, turned out for the Yorkshire Academy in his sixties ("Dad, that Mr Close does swear," reported an awe-struck 16-year-old). Brian Close was unique.

In his career with Yorkshire, Somerset and England he scored 35,000 runs at an average of 33, including 52 centuries, took 1,171 wickets at 26 apiece and also made 814 dismissals, including one stumping. He worked in insurance and had a spell as an England selector.

Dennis Brian Close, cricketer: born Rawdon, Leeds 24 February 1931; CBE 1972; married 1965 Vivienne Lance (one daughter, one son); died 13 September 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments