Muhammad Ali dead: How I travelled the world with a legend

Why Muhammad Ali was the greatest sports figure in history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Muhammad Ali was not someone to argue with, in the ring or out, so when he told the world he was The Greatest, we believed him, because he surely was. Perhaps not the greatest boxer – Ali himself always acknowledged that Sugar Ray Robinson held that title – but certainly the greatest world heavyweight champion, and, as every opinion poll has ever indicated, the greatest sports figure in history.

Even when the dancing years ebbed away and the famous shuffle became no longer a dazzling quickstep but a distressingly slow wobble, he remained until his death the most recognisable human being on earth, and among the best-loved. There has only ever really been one Lord of the Rings. “Parachute me into High Street, China,” he once said, “any every kid would know who I am.”

I was fortunate enough to travel the world with the phenomenon who so ennobled his art that his act as the heavyweight champion of the world has become impossible to follow. Yes, there have been those who have worn the crown, or tawdry, fragmented versions of it, since but none with such style, such guile, such skill and such charisma.

It is one of life’s great ironies that the greatest orator sport has known, the street poet of pugilism was in his later years reduced to a shambling shadow of his erstwhile self because of Parkinson’s Syndrome, the nerve-paralysing condition inherited from his house painter father that was probably precipitated by having ten fights too many. Alas, he never was the retiring sort.

One of Ali’s nine children, Hana tells a story which probably sums up what the world felt about her father. She recalled how, soon after he became ill, she met him for a pizza dinner near her home in Los Angeles. Afterwards as they finished and walked out into the balmy California evening, a tramp approached. “He smelled quite badly and was in a terrible, filthy state. I reached into my purse to give him some money but the vagrant shook his head and said “No. I just want to hug your dad.”

“Before I knew it Dad had his arms around this man and was hugging him in the middle of the street. Both of them were crying. Then dad took him inside the restaurant, ordered him a meal, and sat with him.”

Primary school teacher Hana and her sister Laila (who boxed professionally herself, much to her father's chagrin, and became world champion, but has now retired), were born during Ali’s third marriage to model Veronica Porsche. He had four other children, including identical twins, with second wife Belinda and two others were born out of wedlock to two different women.

Ali always was a ladies’ man and it was the ladies in his life, those who were his family, who nurtured and cared for him. “It was difficult for him to be a normal father because we had to share him with the world but when I see how other celebrities mess up their lives I realise he did a great,” said Hana

Philanderer he may have been in his boxing years – Dundee once caught him having sex with a female journalist after a title fight weigh-in - but in retirement it was the love of one good woman that helped keep him alive. His fourth wife, Lonnie, had devoted her life to nursing him since they were married in 1986. Ali called her "The Boss". She accompanied him everywhere, controlling his life and the purse strings. Although much of the fortune he had earned in his fighting years had dwindled, he was still able to live in comfortably as The People’s Champion, earning considerable sums from personal appearances that enabled him to afford the much needed medical care. Unlike some of his predecessors he was never destined to end up destitute. But money was not the most compelling reason that kept him in the spotlight. “The trouble with Ali is that he doesn’t know how to die,” Joe Frazier once remarked.

“He simply couldn't bear to fade away or be forgotten. Being who he is, is his lifeblood," Lonnie said. She is witty, smart and gracious, a business graduate of Vanderbilt University who started cooking for him when he was getting sick.

A tall, striking woman, she grew up as Yolanda Williams and has known Ali since she was a five-year- old living opposite his family home in Louisville. She remembers him as Cassius Clay, coming home from training camp: "He just wanted to be with the kids from the neighbourhood. He had this great big bus, and he'd take us all over Louisville. He'd shout, `Who's the Greatest?' We'd all answer, ‘You are!' "

Lonnie reckons that by the time she was 14 she was in love with him. "It wasn't just a schoolgirl crush. I knew in my heart I was supposed to be with him."

Three marriages, and three horrendously expensive divorce settlements, later, they met up again in very different circumstances. He had been through a savage beating in his penultimate fight, against Larry Holmes in 1980. "I met him one day for lunch in Louisville and he stumbled getting out of the hotel lift. Something was obviously wrong. Then a friend told me he was sick and needed someone to take care of him, or he might die."

So Lonnie, who had just graduated, gave up her job with Kraft Foods and flew to Los Angeles, where he then lived. "He needed someone to be by his side and I was proud to be that someone." He was diagnosed with Parkinson's in 1985 and they were married a year later.

He and their adopted son, Assam, lived in near Michigan farmhouse, which used to be one of Al Capone's hideouts, where with her guiding hand on his arm, he did what he always did best, and be himself, the People's Champion. “There was a quality about Muhammad that makes you want to give him all the love in the world,” she said. “He is a warrior. He has always needed something to battle over."

Certainly Ali was no saint. He had his dark side particularly in his the early days of conversion Islam and him joining the Black Muslims. His refusal to be drafted for the Vietnam War led to a five-year prison sentence which he successfully appealed but only after being exiled for three years, at the peak of his career, from boxing. But for a fighting man there was an absence of malice outside the ring and throughout his illness he never had an ounce of self-pity, and he remained as generous with his time as he was, in his heyday, with his money. He was strong, but never militant in his Muslim beliefs, immediately and publicly condemning the 9/11 terrorism attacks.

Ali, born as Cassius Clay on 17 January 1942, was a world champion in every sense, traversing all continents to defend a title which he won a record three times in a 21-year, 61 fight professional career, of which he lost five. He finally retired in December 1981 following a humbling defeat by Trevor Berbick.

Throughout his life his closest friend had always been the photographer Howard Bingham, a pal from their Louisville childhood, who was always at his elbow. But the gentle, grey-bearded Bingham was no bodyguard. Ali never needed one, for as Bingham said, “Who on earth would want to harm him?”

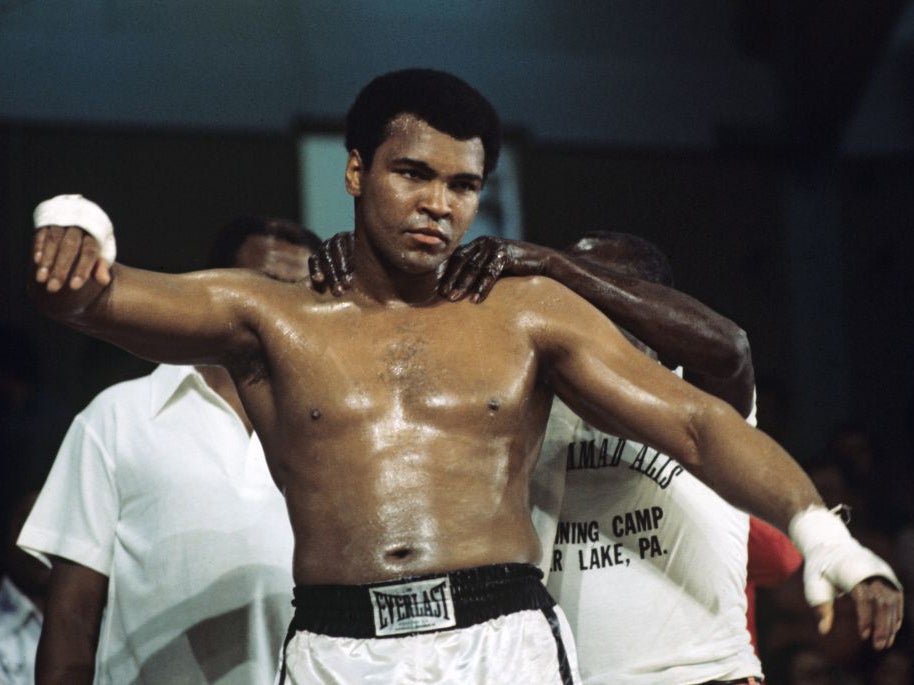

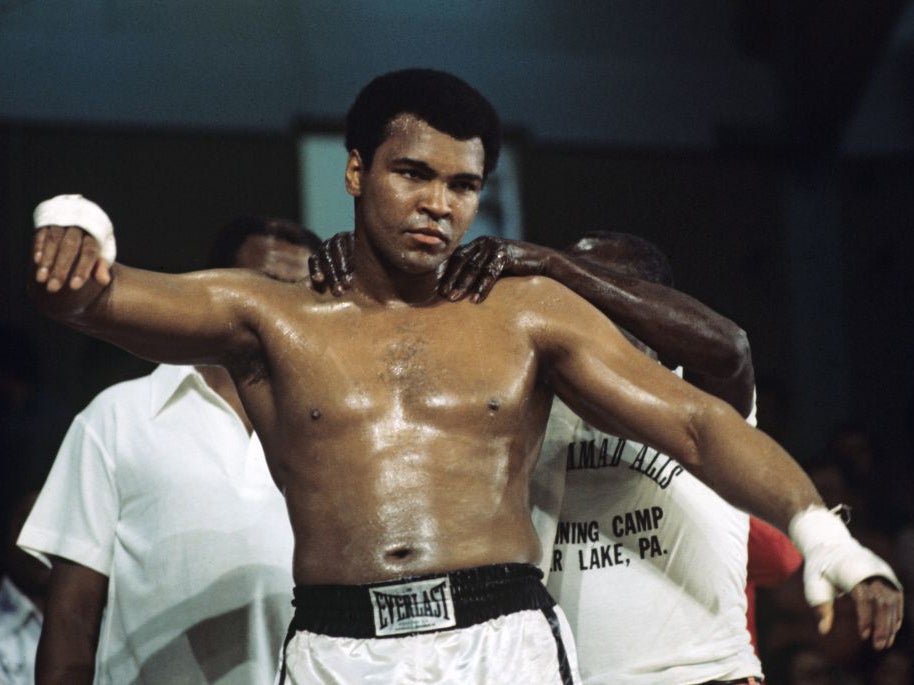

The charisma remained undimmed, despite the toll that Parkinson’s and those last few fateful punches took. In recent years it was not so much shaking the hand of Ali that brought a lump to the throat, but the shaking hand of Ali. Those of us privileged to have travelled the world with him, covering his fights from Atlanta to Zaire, Madison Square Garden to Manila could never countenanced such tragedy would engulf him because of who he was, what he had achieved and the prospect of what he might have become. The greatest irony of all is that while Parkinson’s did not affect his brain he struggled to get out the words that were once his trademark because his facial muscles were paralysed. Never has a face been more photographed. Ali was not only the snapper’s delight, he was the scribe’s dream. No interview was ever spurned, no agent barred the path, no fee was ever demanded.

Being a sportswriter in the Ali era was bliss. Media groupies we may have been, but we were never short of a storyline. Those were the days when we, too, were kings.

Once, back in the 70’s, on arriving to interview him in Dublin, we discovered that Ali was flu-stricken and being attended by a doctor in his hotel bedroom. We explained to his trainer, Angelo Dundee, that we hoped to talk to Ali for ten minutes. "No chance.” Came the reply. “He never talks to anyone for less than an hour.” He phoned Ali’s room, “Hey Champ, some Lime press guys’ here to see you…” He put the phone down and said, “Muhammad says, go on up.” We emerged a good two hours later with notebooks overflowing.

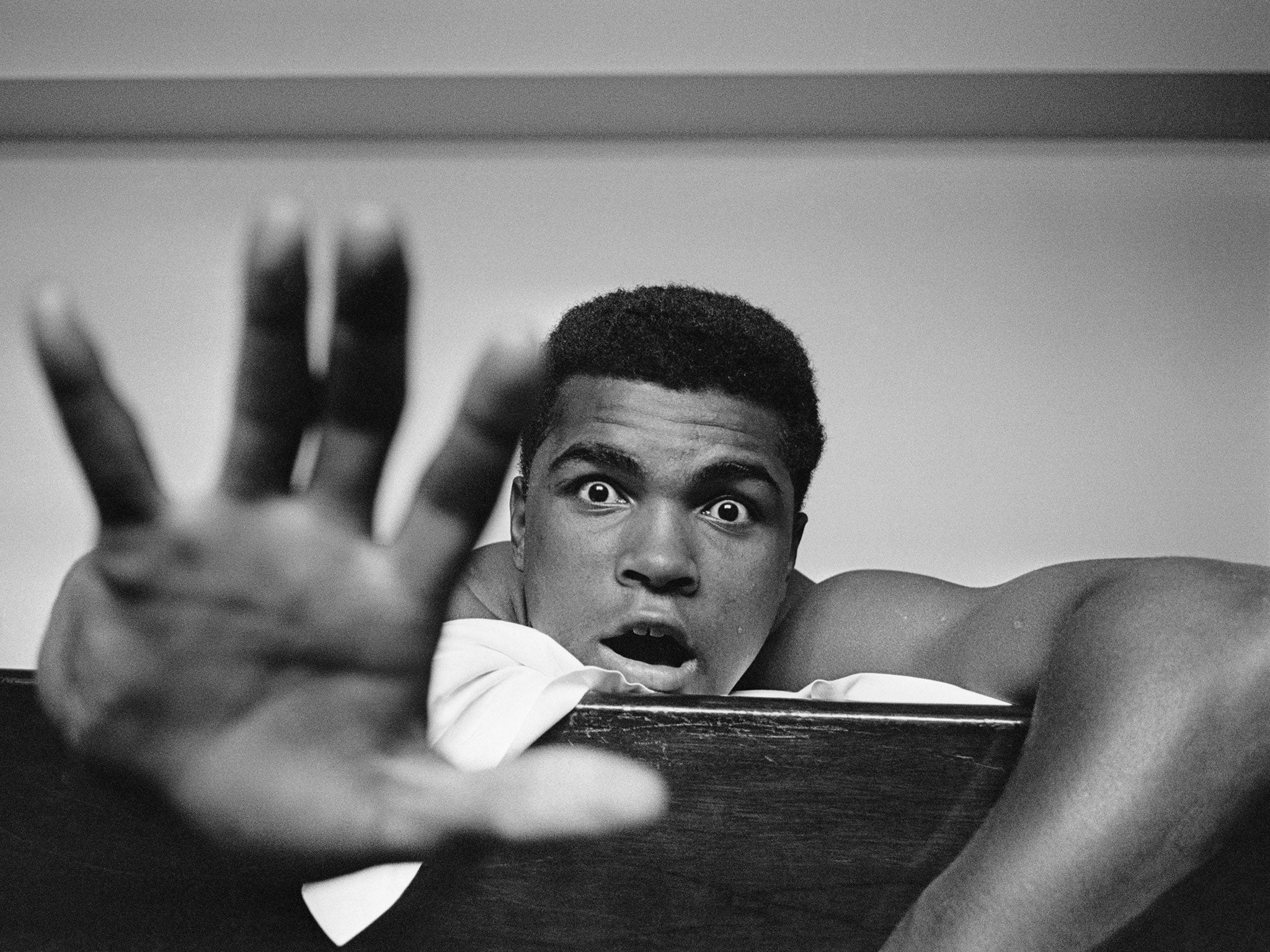

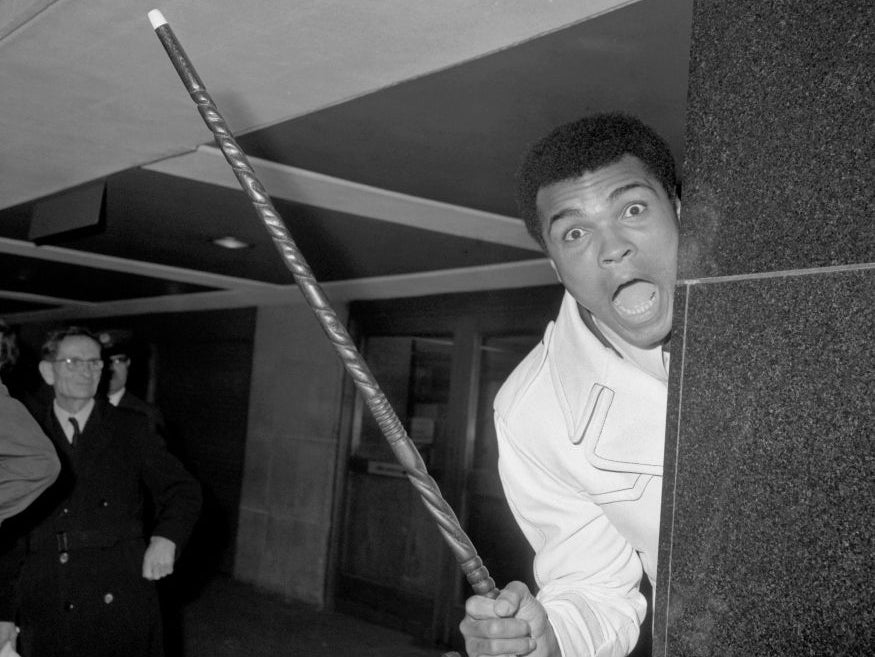

“Ahm sooooo pretty”, he would say, patting the features that captivated the world.And he was, transcending boxing almost from the moment he won the Olympic light-heavyweight title in Rome in 1960 with a fleet-footed, backward leaning technique that defied all the sacred norms of the sport. The ‘Louisville Lip’ was floating like a butterfly and stinging like a bee well before another of his acolytes, Drew ‘Budini’ Brown, coined the most famous phrase in sport.

From his early days in Louisville, Ali lived for the limelight, soaking up the adoration of the fans and celebrities which fuelled his very existence, whether Rumbling in the Jungle or Thrilling in Manila.

In 1964, when he challenged the Mafia-run Sonny Liston, a seemingly indomitable ogre as a 22 year old, he indeed “shocked the world” twice, first by forcing Liston to retire on his stool after the sixth round and then announcing that Cassius Clay (“My slave name”) was no more and that he had accepted the teachings of Islam and the influence of Malcolm X and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. “Until then”, Angelo Dundee said, “I always thought Muslim was a piece of cloth.”

Ali reigned in an age when world boxing crowns were not bits of bling. He fought, and beat everyone of note as well as many others of little consequence. No challenge was shirked, though some proved more difficult than others. His three fights with Ken Norton, for instance, in one of which his jaw was broken, all ended in controversial points decisions.

Ali had a particular affection for Britain, and the British for him. “How’s Henry Cooper,” was the first question he would ask whenever he encountered a British scribe. It was in 1963, when, still as Cassius Clay, he was put on the floor at Wembley Stadium by ‘Enery’s ’ammer, the left hook he did not see coming because he was too busy glancing down at Elizabeth Taylor, who was at ringside. “Hiya Cleopatra,” he mouthed, just before Cooper caught him. Right up until his death in 2011 Cooper argued that in the corner Dundee deliberately worsened a tear in Ali’s glove to give him an extra minute’s recovery time but the interval in fact lasted only a few seconds longer than scheduled. Ali, of course, cut Cooper’s eyebrow to salvage his prediction of a fifth round victory, and similar damage ended their title fight at Highbury three years later.

In more than half century of sports writing I confess the only time I shed a tear was on the night of 2 October 1980, when in a stadium built in the car park of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, Ali, old, out of shape and clearly unwell, was battered to defeat by Holmes. Like Holmes himself, we pleaded with the referee to stop the fight, which Dundee did at the end of the eleventh round. The lumps in our throats were as huge as the one covering Ali’s eye.

Ali fought his share of bums in his 61 fights, as most heavyweight champions do, but was always generous in victory even if he had been outrageously uncharitable in the build-up, always with an eye on the ticket sales. When he fought the hapless Briton Richard Dunn in Munich the US television network screening the bout had begged him to at least let it go seven rounds, because they had sold so much advertising. But at the end of the fourth, Ali who had hardly thrown a punch, leaned down to one of the producers and whispered, “Better get those commercials in quick. I can’t hold this sucker up any longer.”

But he also fought and beat the best, George Forman, of course, in the renowned Rumble in the Jungle when he regained the title for the first time at 32, but also Joe Frazier, who had defeated him on his return from exile at Madison Square Garden in 1971. Their third meeting, the Thrilla in Manila four years later, remains etched in the memory as perhaps the greatest heavyweight epic in history. “The closest thing to dying” was how Ali described it, collapsing in relief when half blinded Frazier was retired with just one round remaining.

Later, in a darkened dressing room, Frazier’s then 14-year-old son Marvis sat sobbing alongside his father as Ali entered to offer his commiserations to the bruised and bleeding “Smokin’ Joe, with whom his rivalry had been intensely bitter. “What you cryin’ for, boy?” Ali demanded of young Frazier. “I’m crying’ ‘cos my daddy got beat.” Ali looked down at him, “You stop that you hear. Your daddy lost nuthin’ tonight. He’s a winner. Just you remember that for the rest of your life.”

The one quality about Ali most overlooked was his bravery. He took more punches than he ever needed to, because he wanted to psyche out his opponents. “That your best shot, George,” he enquired of Foreman as swinging punches crunched into his ribs in Kinshasa. “You’re punching like a cissy.” The rope-a-doped Foreman later confessed to being destroyed psychologically before he was physically by the right hand punch in the eighth round that spun him off his feet and caused BBC commentator Harry Carpenter to yell, “Oh my God, he’s won the title back at 32!”

Earnie Shavers, one of the hardest punchers heavyweight boxing, recalls how he hit Ali flush on the chin. “He just stared back at me and said “Show me something, Earnie”. I knew then I was in for a long night. Oh yeah, he was the king alright.”

Ali said later that Shavers had hit him so hard “It shook my kinfolk back in Africa” and the awful legacy of that fight in September 1977 was probably the onset of his illness. He had temporary kidney failure, passed blood for days afterwards and a subsequent scan showed the first signs of torn tissue on the brain. It was then that his personal physician, Dr Ferdie Pacheco, reluctantly ended their relationship after Ali rejected his advice to quit. In the end it was Ali’s own ego which drove him towards his physical destruction.

One of the rare occasions in recent years when Ali had a global audience was as a member of the New York contingent which bid unsuccessfully in Singapore for the 2012 Olympics. They took him along because of the impact he had made on 3 billion viewers when he lit the flame in Atlanta in 1996. But it proved a dreadful mistake. Ali had clearly deteriorated. His movements were painfully slow and robotic, his gaze blank, and unrecognizing, save for the constant blinking of his eyelids.

The last time we had met was during a visit to London a few years earlier, when he received an award as the Sports Personality of the Century. Ali always remembered your face, if not your name and he placed a trembling hand on my shoulder as he leaned down to whisper in my ear. “It ain’t the same any more, is it?”

“No champ,” I replied, “It ain’t.”

Nor can it ever be now that the Greatest has gone. Finally, a legend has been licked.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments