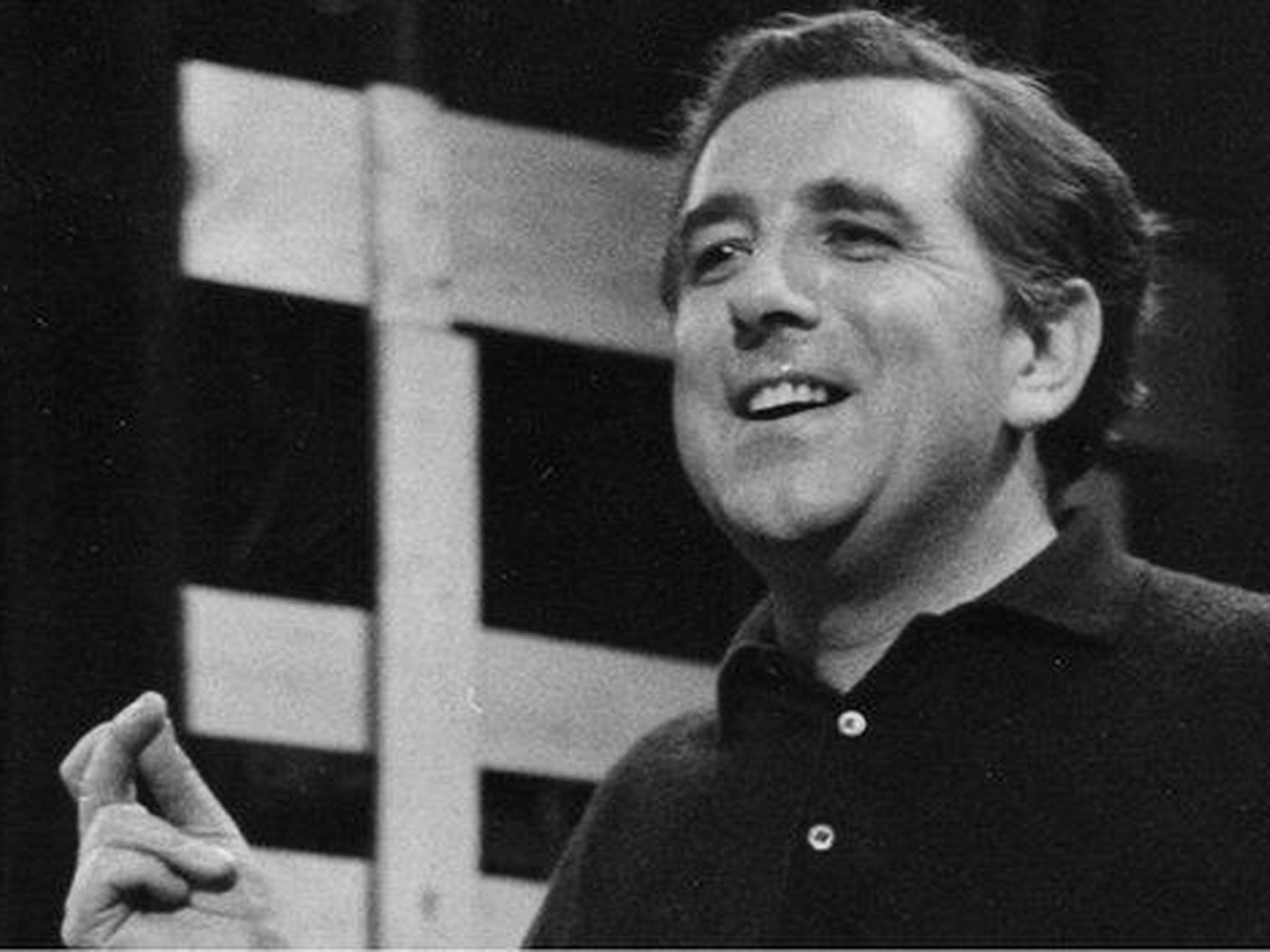

Meredydd Evans: Writer and broadcaster who devoted his life and career to the cultural and linguistic health of his beloved Wales

Not for him corporate bureaucracy or the narrow specialism of Academe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There seemed to be more than one Meredydd Evans. So numerous were his talents, and so prodigally did he scatter them, that his name crops up in discussion of almost every sphere of Welsh cultural life, from folk music and philosophy to broadcasting and language politics.

Not for him the narrow specialism of Academe or the dull routine of corporate bureaucracy, though he taught philosophy at Boston University and, from 1963-73, was Head of Light Entertainment at BBC Wales. Nor was he averse to mixing serious and popular: he wrote an acclaimed study of the Scottish philosopher David Hume but also, in his light tenor, sang some of the most charming songs ever heard on Welsh radio, earning him (much to his chagrin) the accolade “the Welsh Bing”.

He composed the haunting music for “Colli Iaith” (Losing a Language), a patriotic poem by Harri Webb which has has achieved the status of a traditional air, and wrote extensively on the plygain carols (from the Latin pulli cantus, cock crow), sung in the early hours of Christmas morning since pre-Reformation times.

If he did not give his whole mind to philosophy or to entertainment for long, it was because he saw the need to work on a broad front and he was not bothered when his friends complained that as a philosopher he was not serious enough and as an entertainer, too much so.

It says much for his commitment to Welsh, his first language, that he put his career in jeopardy by his support for Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (The Welsh Language Society). This militancy, and his support for language campaigners in court and jail, almost certainly cost him the job of Controller of BBC Wales, for which he was hotly tipped, and made him something of a bête noire in Establishment circles.

Undeterred, in 1980, with two other senior academics, Ned Thomas and Pennar Davies, he broke into and switched off a television transmitter at Pencarreg in Cardiganshire in a symbolic protest against the Conservative government’s dragging its feet over the establishment of S4C, the fourth television channel. For his speech from the dock, a classic statement of Welsh nationalism, which in his case was grounded in the language, he won a wide measure of admiration from young activists.

But during the late 1990s the channel proved a disappointment to Meredydd Evans, mainly on account of its readiness to allow a certain amount of English in its Welsh-language programmes, arguing from the fundamental principle that the Welsh speaker has a moral right to a full service in his or her own language.

He remained a critic of those at the channel’s helm and, as a leading member of Cylch yr laith (The Language Group), spearheading the campaign against the intrusion of English on Welsh radio and TV, took on BBC Cymru. He was fined more than once for refusing to pay for a TV licence, escaping prison only after unidentified supporters paid the fines.

His last skirmish, interrupted only by ill health and surgery, was a forlorn attempt to dissuade Welsh broadcasters from using material by non-Welsh artists, against the trend now firmly established in the Welsh pop industry.

Although he was an effective public speaker, there was nothing of the firebrand about Mered, as he was known: the gentlest of zealots, and the most amiable of men, he always argued from the highest intellectual ground and in a dignified manner which most broadcasting executives found disconcerting. A native of Llanegryn in Merioneth, he was brought up at Tanygrisiau in the slate-quarrying district of Blaenau Ffestiniog. Obliged by his father’s ill-health to leave school at 14, he worked for seven years in the Co-op, entering the University College of North Wales, Bangor, in 1940, taking a first in philosophy. He went to Princeton, where he was awarded his doctorate, and from 1955 to 1960 he taught at Boston, where in 1957 the students voted him Professor of the Year.

It was in the US that he met and married Phyllis Kinney, an opera singer, who learned Welsh and shared his keen interest in folk song. They collaborated on books and records as entertaining as they were informative. The songs, Welsh and American, were often illustrated by duets notable for their clarity of diction and an infallible sense of the authentic flavour of the music. The Folkways album he brought out in 1954 was selected by The New York Times as one of the year’s dozen best folk records.

Evans had made his name as an accomplished vocalist at Bangor, where he and two friends formed the close-harmony group Triawd y Coleg (The College Trio). Whenever they sang on Noson Lawen it was said that the streets of North Wales emptied for half an hour. He became a regular participant in radio programmes as singer and presenter. In 1963 be left his post as Tutor in the Department of Adult Education at Bangor to become Head of Light Entertainment with BBC Wales in Cardiff.

He was responsible for a number of popular programmes featuring the comic genius Ryan Davies, notably Fo a Fe, in which a beery, loquacious, Marxist collier from South Wales, played by Davies, came into weekly conflict with a sanctimonious, organ-playing, teetotal, Liberal deacon from the North played by Guto Roberts. The series is regularly repeated as one of the finest productions from the “golden age” of Welsh light entertainment.

But Evans was too much of a rebel, or perhaps not pin-striped enough, to be a Corporation man and in 1973 he took up a post as Tutor in the Department of Extra-Mural Studies at University College, Cardiff, where he remained until his retirement in 1985. He turned to writing for the Welsh academic press. In nothing he wrote did he make any concession to the reader looking for simplification of complex matters, but in his 1984 study of the sceptic Hume, he discussed with great lucidity the nature of knowledge and, inter alia, the principle of cause and effect.

His religious beliefs were Christian but unorthodox. In a 1984 S4C interview he explained how he had thought himself unworthy of the ministry he had at first contemplated, how his reading of Hume had made him ever more questioning, and how he had struggled to regain his faith under the influence of WT Stace, one of his professors at Princeton.

At the heart of his beliefs – he had been a Labour Party member but joined Plaid Cymru in 1960 – was the Welsh language, which he saw as a bastion against the uniformity imposed by the State. He explored this problem in the conviction that the dissident is a key figure and, in the Welsh context, that the defence of national identity against the centralism of the British state is a condition of civilisation in its fullest sense. His major lecture on civil disobedience, in which he explored the example of Gandhi and its relevance to Wales, appeared in Efrydiau Athronyddol in 1994, the same year a selection from his scholarly writings was published.

In 1973 he helped launch Y Dinesydd (The Citizen), a monthly freebie for the 30,000 Welsh-speakers in Cardiff which still flourishes. Relying for its early success on his enthusiasm and expertise, it was the first of some 50 community newspapers written in Welsh which are now published in most parts of Wales.

What drove Evans in his tireless campaign against the anglicisation of Wales, besides the shortcomings of the broadcasting authorities, was the English influx into the Welsh-speaking heartlands. He had first-hand experience after he left Cardiff to live in Cwmystwyth, a village to the south of Aberystwyth in a district fast losing its Welsh under pressure from incomers. The social fabric of the valley was being adversely affected by second homes , and retired Midlanders who seemed unaware of the damage to the indigenous culture.

In 1987, from the stage of the National Eisteddfod, he spoke out with typical fearlessness against local authorities which allowed this to happen, for which he was accused of being anti-English in some quarters. Many shared his view, but he was the first to express it so forthrightly.

Meredydd Evans, broadcaster, teacher and activist: born Llanegryn, Merioneth 9 December 1919; married 1948 Phyllis Kinney (one daughter); died 21 February 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments