Margaret Thatcher told by press secretary Bernard Ingham that public thought she had 'dictatorial personality'

Public opinion had turned against the PM in 1985 – forcing her ultra-loyal press secretary, Bernard Ingham, to confront her

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Margaret Thatcher was warned half way through her premiership that in the eyes of the public she was a “hectoring, strident, bossy and dictatorial personality”.

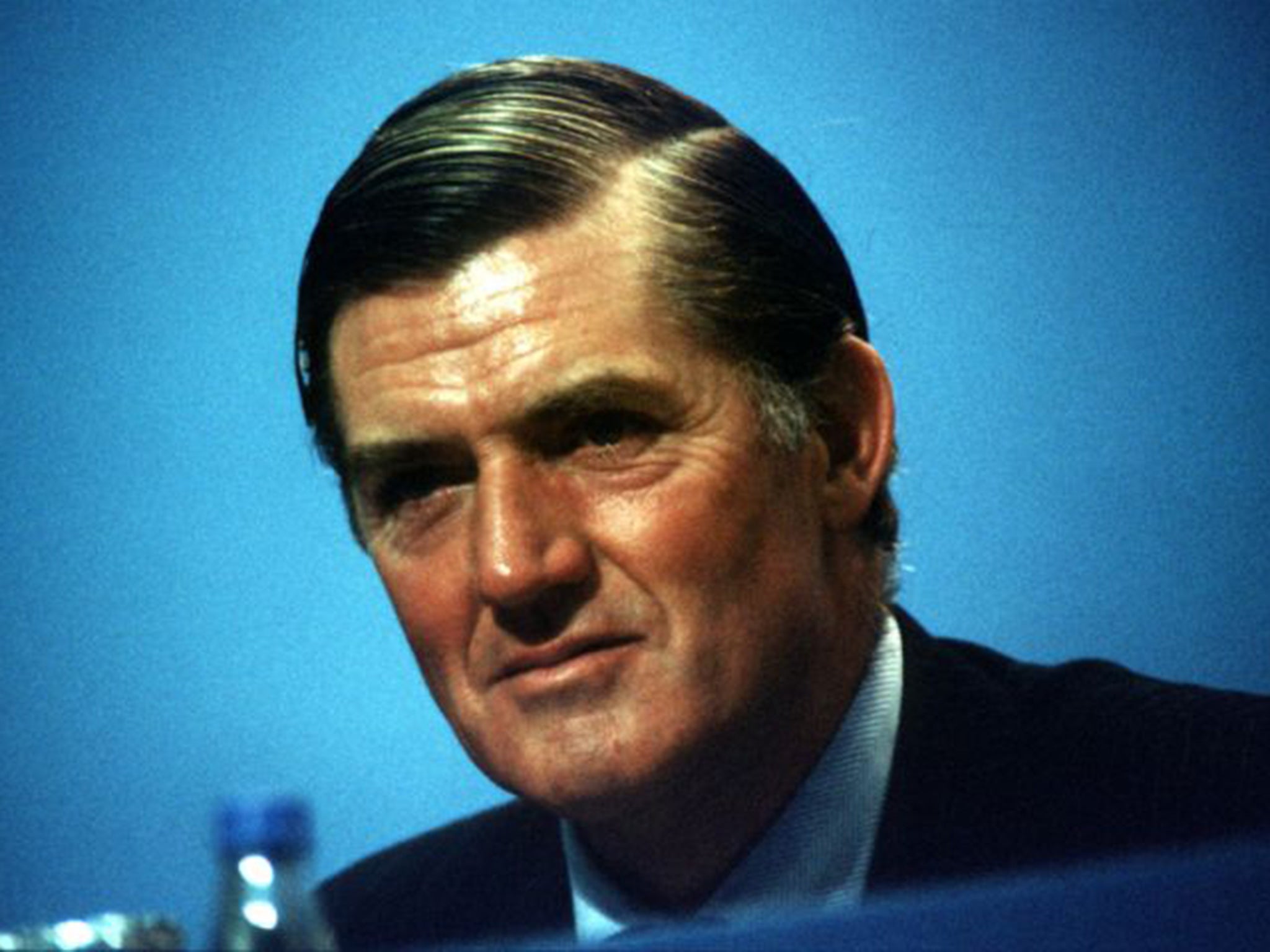

It was not one of her political enemies who used those words. They were in a private memo sent to her by her loyal and long-serving press secretary, Bernard Ingham. And far from being offended, she appears to have accepted that such a reputation was an unavoidable consequence of getting her way.

Documents newly released by the Margaret Thatcher Archive Trust, in Churchill College, Cambridge, reveal that the Conservatives were worried that their popularity was sinking in the second half of 1985, after they had won their epic battle against the striking miners.

In July, an opinion poll showed Labour on 42 per cent, with the Tories trailing behind the Liberal-SDP Alliance on 23 per cent. Three months later, Ingham sent the Prime Minister a press digest which showed that even the Daily Mail was praising the Labour leader Neil Kinnock for his “courage” in standing up to the hard left.

In his five-page memo, Ingham – who worked for Thatcher throughout her 11 years in No 10 – went out of his way to stress that he personally did not think she was “dictatorial”, but rather that she was a “decisive strong-minded person” and “someone who is clearly going to be very hard to beat”.

Thatcher did not reply to Ingham’s memo, although earlier in the year, she defended herself when the TV AM interviewer, David Frost, put it to her – rather more tactfully – that some people saw her as “intolerant” and “uncaring”. Instead of claiming that she was actually tolerant and caring, as other politicians might, she replied: “You do have to be firm sometimes.”

Chris Collins, a historian who has studied the archive, said: “Looking at this document, there is no sign of massive dissent from Thatcher – no scribbled notes or underlining, like you often see on her personal files. It is nothing he wouldn’t have said to her before.

“She simply would never have worn her heart on her sleeve like that, partly because it would have gone against her instincts but also because, by that point, it would have seemed inauthentic.”

Ingham gave Thatcher the bad news in October 1985, as the Conservatives prepared for their conference after Kinnock had dramatically denounced Liverpool’s left-wing council at the Labour conference.

Later the same month – perhaps to cheer her up – he sent her another list of headlines, which demonstrated that feuds on the left were still making the news. They included one that said: “Robert Kilroy-Silk in Commons scuffle with Jeremy Corbyn.”

Kilroy-Silk was a Labour shadow minister, who quit the Commons for a television career soon after his altercation with Corbyn, claiming that he was being hounded by the hard left, then joined Ukip, then fell out with it and formed his own short-lived political party. He boasted “I didn’t really hit him. If I had, he’d have stayed down.” Corbyn, who was a newly elected Labour MP, does not appear to have given journalists his side of the story.

As Labour’s popularity recovered, people around Thatcher worried that her government was not getting its message across. William Davis, the former editor of Punch magazine and one of the unofficial advisers from whom Thatcher took soundings, blamed the failure on poor TV performances by the holders of the most senior cabinet jobs – Chancellor Nigel Lawson, Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe and Home Secretary Leon Brittan.

In a handwritten note, he claimed all three came across as “grey, dull, uninspiring, self-righteous and smug”. He was particularly scathing about Lawson – who is now back in the public eye as President of Conservatives for Britain, an anti-EU pressure group. “At school he was known as ‘smuggins’. Nothing much has changed,” Davis wrote.

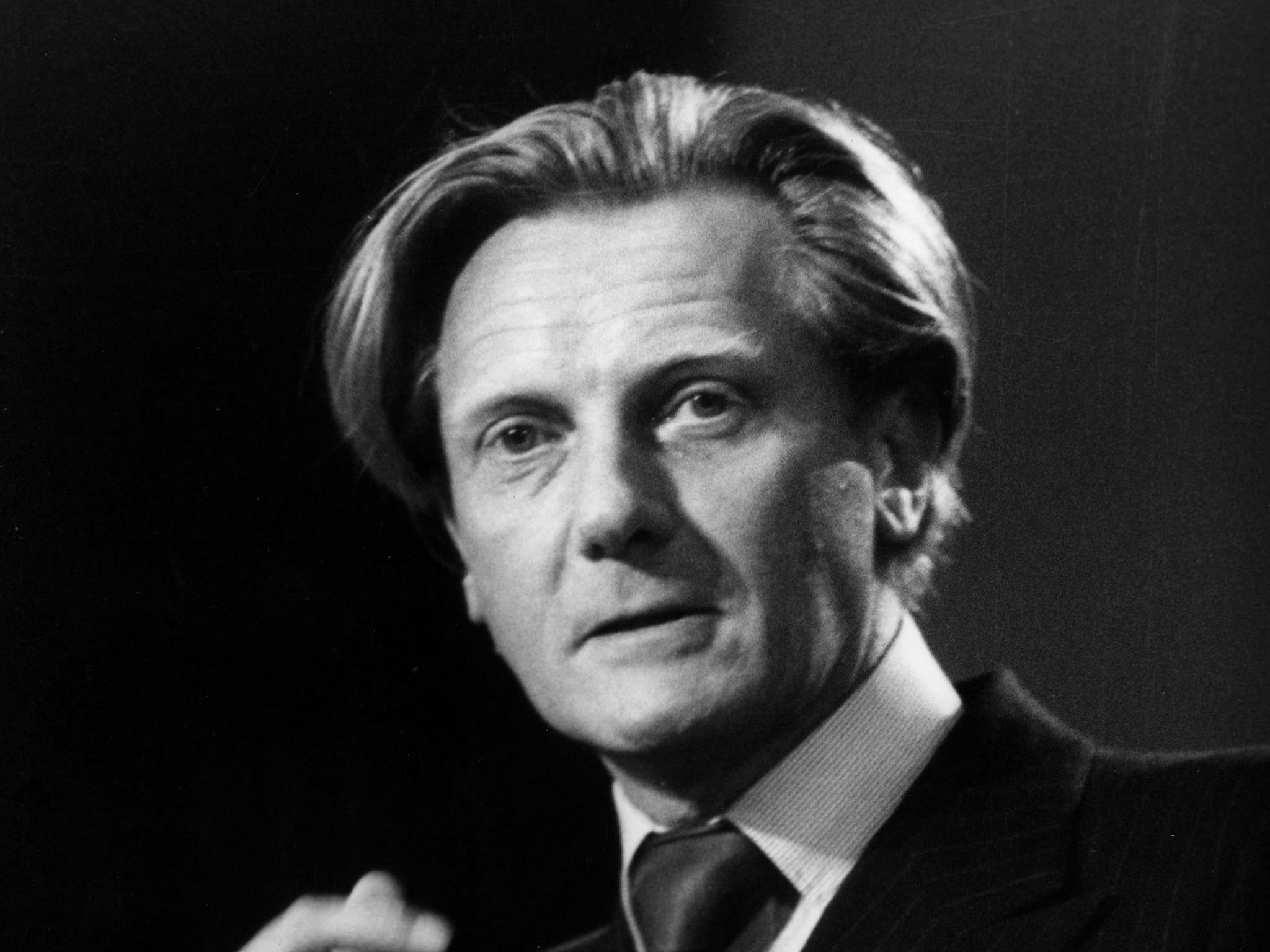

The absence of good television performers prompted Thatcher to consider reinstating her favourite, Cecil Parkinson, as Trade and Secretary Industry – the job he had been forced to leave less than two years earlier because of a sex scandal. Davis urged her to bring him back, because he was “handsome, likeable and able to communicate in plain English”. Davis believed the public had forgiven Parkinson for his affair with his secretary, Sara Keays, whom he promised to marry when she became pregnant, but then abandoned.

Thatcher certainly had: a note in the archives shows that she accepted a dinner invitation at the Parkinsons’ London home in March 1985. She wrote to Ann Parkinson afterwards, but a note in the archive says that “it was not copied”, so her civil servants did not know what she had said.

Her political secretary, Stephen Sherbourne, warned that bringing back Parkinson would be “high risk” because there might be more revelations “that could rebound on you and not just him”.

And Viscount Watkinson, a former Conservative cabinet minister, pleaded with her, in a handwritten letter, not to reappoint him. He wrote: “The moral issue troubles many of us, but it is his lack of judgement as a member of Cabinet that really matters.”

A note in the archive said that Thatcher was going to speak to Parkinson personally to tell him he would not make a comeback that year. Had he been appointed, he would inevitably have been caught up in the controversy over the future of the Westland helicopter firm, which tore the cabinet apart four months later, and forced the new Trade and Industry Secretary, Leon Brittan, to resign.

‘Explosive’ reaction to Falklands memorial snub

Margaret Thatcher reacted furiously to being told that church leaders planned to keep her out of a ceremony at which the Queen unveiled a plaque commemorating victims of the Falklands War.

As church officials put together the arrangements for the ceremony, held in a crypt at St Paul’s Cathedral in June 1985, they decided that there had to be 13 members of the clergy present along with five royalty, and – given the small size of the crypt – there consequently would not be any room for Thatcher.

There had already been a row between the Prime Minister and the church after the Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, had insisted that the service held after the return of the Falklands task force should be on the theme of peace, rather than victory.

However, the Defence Secretary, Michael Heseltine, unwisely allowed Thatcher to see a letter from the Ministry of Defence in which they accepted the church’s arrangement for the unveiling.

She reacted “explosively” and scrawled on the letter: “Kindly ask the secretary of state to see me immediately.” The word “immediately” was underlined twice. Heseltine apologised, and went to inspect the crypt in person.

The public can browse the archive from 12 October by visiting margaretthatcher.org.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments