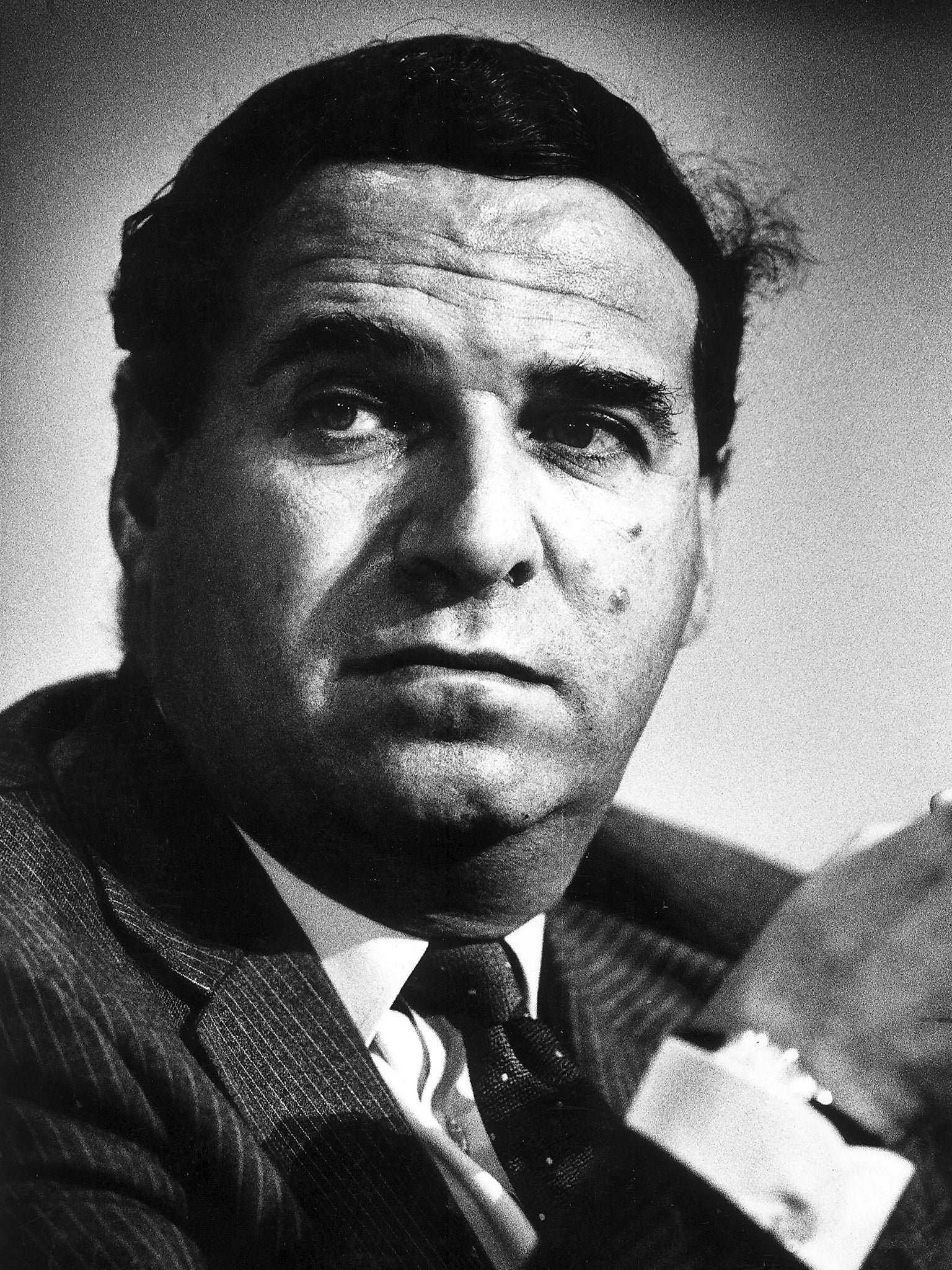

Leon Brittan: Tory Home Secretary whose rise was halted by Westland affair

Brittan's elevation in 1983 to Home Secretary at the age of 43 was remarkable but his career prematurely ended over ministerial divisions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As a high-flying Cabinet minister under Mrs Thatcher, Leon Brittan was involved in a political drama – over the rescue of Westland helicopters in 1986 – which, by her own admission, nearly toppled her. His rise to high office had been rapid, but Westland brought it to an abrupt end.

Brittan's grandparents were Lithuanian Jews. His father, an immigrant in the 1920s, was a Willesden GP who had formidably intellectual offspring. Samuel Brittan, later knighted, was a brilliant economist who became chief economic commentator on the Financial Times. The younger Leon, born in 1939, won a scholarship to Haberdashers' Aske's and another to Trinity College, Cambridge. He graduated with a First in Law, was chairman of the university Conservative Association and president of the Union. Fellow Tory students included Michael Howard, Kenneth Clarke and John Selwyn Gummer; he was the first to reach the cabinet.

He was called to the Bar in 1962, specialised in defamation, became a QC, and without doubt would have gone far had he not decided on a political career. He was chairman of the Bow Group, edited its magazine, Crossbow (1966-69), but found it difficult to gain selection for a winnable seat. In February 1974 he won the marginal Cleveland and Whitby seat in the north-east. He held it until 1983, when it disappeared in a boundary review. He was then selected for the safe Richmond constituency in North Yorkshire.

In 1979 he was appointed Minister of State at the Home Office, where he impressed the Home Secretary and Deputy Prime Minister William Whitelaw. Brittan never had a popular following among MPs but his brain power and application impressed senior figures. Another admirer was Sir Geoffrey Howe, the Chancellor, and in 1981 Brittan entered the Cabinet, its youngest member, as Chief Secretary. His job was to agree (usually by whittling down) spending bids from departments and he recouped much of the ground lost by his predecessor, John Biffen. He also handled the annual finance bill and spoke authoritatively for the Treasury.

In 1975 he had voted for Sir Geoffrey in the first leadership ballot in which Thatcher defeated Ted Heath. Like Howe, he combined a belief in free market economics and liberal social policies and was pro-European.

Brittan's elevation in 1983 to Home Secretary, one of three great offices of state, was remarkable. He was 43 and had been in Cabinet only two years. Douglas Hurd, a junior minister in the department, regarded him as the best minister he worked with. The major legislation during his tenure was the complex Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) which regulated many of the interactions the police had with the public and alleged offenders. It proved for careful record-taking by police, tape-recording of interrogations and a suspect's right to legal assistance before charge.

Under pressure from No 10 he wrote to the BBC asking it to withdraw the Real Lives television documentary which featured an interview with an IRA terrorist. The withdrawal of the programme led to a strike among BBC staff and accusations of government censorship. In 1985, to his disappointment, he moved to Trade and Industry, which proved to be unfortunate.

Brittan's strength was his ability to master not just a brief but the details of the case under discussion. He was also quick to see the broad outline of a political argument. At the despatch box or in interview he was commanding, invariably well-informed and able to dismantle opposition. His face was distinctive, with his narrow eyes, furrowed brow and a habit of grimacing when on the attack. This demeanour did not always transfer well to television; Thatcher once glanced at a television screen when he was speaking and remarked to an aide, "Isn't he unattractive?"

His career was prematurely ended over ministerial divisions about the best scheme for rescuing the troubled Westland helicopter company. Michael Heseltine, the Defence Secretary, favoured a deal with a European consortium. Mrs Thatcher and Brittan, although appearing to be open-minded, favoured a link with an American company, Sikorsky. The disagreements between the two camps were aired across the mass media in late 1985 and Thatcher thought Brittan should be making a stronger case.

Brittan authorised his officials to leak parts of a letter from the Solicitor-General stating that there were "material inaccuracies" in some of Heseltine's claims. The letter was provided by No 10 and he thought he had clearance from the Prime Minister. Then things became murkier. Leaking confidential legal advice given to the government was a serious matter – and an inquiry was launched.

When on 9 January 1986 Thatcher told Cabinet that future statements about Westland had to be cleared with the Cabinet Office, Heseltine, spotting that he was being denied the chance to put his case, marched out and announced his resignation. It then emerged that Brittan had tried earlier to persuade British Aerospace and GEC to withdraw from Heseltine's preferred European consortium. Conservative MPs were unhappy with his lawyerly answers and he was summoned to meet the 1922 Committee of backbench Tory MPs.

Although gregarious, his lack of a following in the party proved fatal. There was a whiff of anti-semitism in the reaction of some Tory MPs. One likened him to a "cornered rat" and another called for his replacement by "a red-blooded Englishman". There were six Jews in the Cabinet – and Harold Macmillan quipped that it contained more Estonians than Etonians.

He resigned with great reluctance; he was the fall guy to save the skin of Thatcher and some No 10 staff. In her response to his resignation letter she wrote that she looked forward to his "return to high office to continue your ministerial career". That expectation sustained him on the backbenches. But over time she seemed to become disenchanted with him; perhaps he was a reminder of the unhappy episode. When she summoned him to No 10 in 1989, it was not to offer an expected return to the Cabinet, but exile to Brussels as a European Commissioner. His complaint at not being invited to rejoin the Cabinet brought no response from her. He resigned his Richmond seat which was won at a by-election by the 28-year-old William Hague. Brittan's Parliamentary career was over.

In Brussels he took the post of Competition Commissioner and later the posts for Trade and then External Affairs. As Trade Commissioner he was an effective EU negotiator in the final stages of the GATT agreement. He also canvassed support for an ambitious free trade agreement between the EU and the US that was ahead of its time. In 1994 John Major felt that he had to support what was his hopeless candidacy as Commission President; Brittan's friends had failed to dissuade him. He was faced by two long-serving Prime Ministers, from Belgium and Luxembourg, his liberal free-trading instincts irritated the French, and it did not help that he had no foreign languages except rudimentary French.

In 1996 he appointed Nick Clegg to his "cabinet" or private office. So impressed was he by Clegg that he tried to recruit him to the Conservative cause; this failed because Clegg was unhappy with Conservative attitudes to the EU. Brittan recommended him to Paddy Ashdown, the Lib Dem leader.

He resigned from his Brussels duties after ten years and returned to England. In 2000 he took a life peerage and the title of Brittan of Spennithorne, the place where he lived in North Yorkshire. He was chancellor of Teesside University and vice-chairman of UBS Investment Bank. His last years were marred by cancer and allegations that a dossier that a Conservative MP had handed to him as Home Secretary about paedophile activities by prominent people in public life had gone missing. Critics claimed that he had not acted on the dossier.

He is survived by his wife, Diana, who was a chairman of the National Lottery Charities Board, and two stepdaughters.

Dennis Kavanagh

Leon Brittan, politician: born 25 September 1939; married Diana Clemetson (two stepdaughters); died London 21 January 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments