Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page: Why I assembled a 40th-anniversary edition of Physical Graffiti

'What does matter is that we’ve managed to make a difference and quite clearly Led Zeppelin’s music did'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

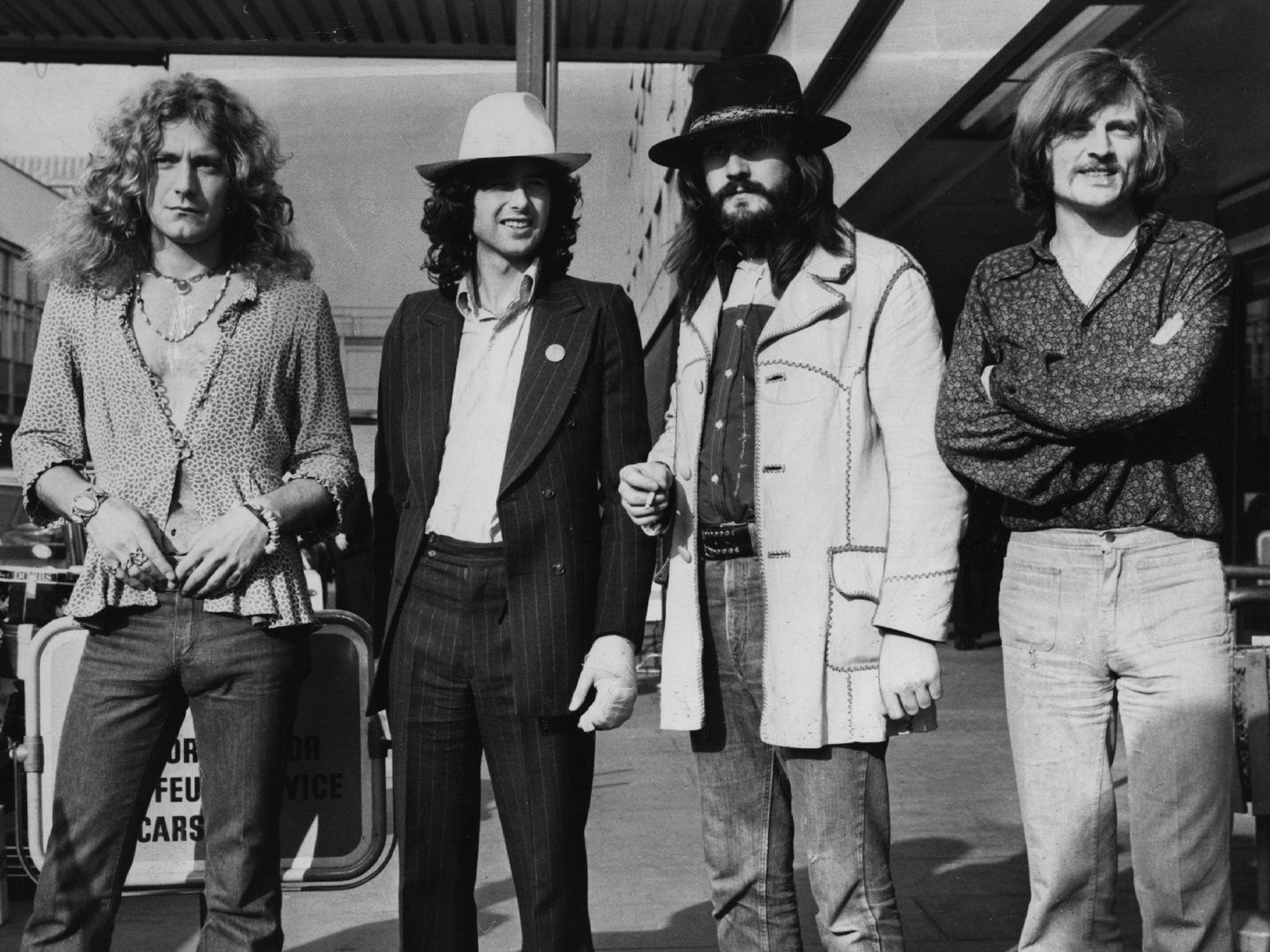

Your support makes all the difference.So many myths have grown around Led Zeppelin, the British rock band that ruled the Seventies and continues to cast a long shadow over popular music, that their guitarist, producer and curator extraordinaire Jimmy Page has to see the funny side. The 71-year-old’s hair may be snow-white but his black-clad frame is as pencil-thin as it was in his prime. The years roll back while we converse in front of a roaring fire, in a plush Kensington hotel, a stone’s throw from the Royal Albert Hall, where Led Zeppelin triumphed in 1969 and 1970.

He is talking up the 40th-anniversary edition of the double studio set Physical Graffiti, the third tranche of a reissue campaign that kicked off last June. The addition of companion discs containing out-takes, alternative, and rough mixes has returned the group’s first five multi-million-selling albums to the charts, introducing them to yet another new generation of fans.

Page is debunking a story about what happened before the recording of Physical Graffiti started. “On this one, we’re really bouncing. We’ve been touring and we’re going in there and John Paul Jones has left his choir,” he quips, alluding to the rumour that, at the end of 1973, his multi-instrumentalist bandmate considered quitting the biggest group in the world to become a choirmaster at Winchester Cathedral. The truth is more prosaic. “John had a big family and he wasn’t there on the first few days. His holidays over-ran,” he says.

Back in 1973, since vocalist Robert Plant was also late arriving, Page and drummer John Bonham began rehearsing the epic “Kashmir”, the unstoppable, Panzer-like track which typified the ambition and scope of Physical Graffiti. “I had that riff on an acoustic piece I was working on and I also had those staccato parts that became the brass parts. The idea of using the orchestra over that riff goes back to classical music, things like Benjamin Britten’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge and The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra. I knew it was pretty radical. John Bonham understood what it was about. The whole band took to it. “Robert said, ‘oh, I’ve got some lyrics that I wrote before, in Morocco’. He tried them out and they worked really well,” says Page.

As he admits, there was no guarantee the Eastern-flavoured majesty of “Kashmir” was going to translate across to the general public. Yet it became another gem in the superlative Led Zeppelin catalogue, more sonically ambitious than the era-defining “Whole Lotta Love” and “Stairway to Heaven”, and a milestone at the crossroads of world music and rap, recycled by Puff Daddy for “Come With Me” on the soundtrack to the Godzilla blockbuster in 1998. “People went, ‘oh, he shouldn’t have done that’, but you might as well say, ‘oh, he shouldn’t have dabbled in world music’. Of course, I should have. I was doing that as a teenager, so why in heaven’s name not? It’s all part of the big picture,” says Page.

Like many of his contemporaries, he followed up his interest in skiffle, rock’n’roll, folk and world music by delving into the blues. “We were doing the best research before the internet,” he recalls. “I’d include Arabic instruments like the oud and Indian ones like the sitar in that. It was all permeating into my playing, and that grew when I was in the Yardbirds and then Led Zeppelin. But everyone in the band had their own influences.”

In the summer of 1968, Page and Jones considered vocalist Terry “Superlungs” Reid and Procol Harum drummer BJ Wilson but, once they teamed up with Plant and Bonham for that first rehearsal in Soho’s Gerrard Street and started jamming “Train Kept A-Rollin’”, they never looked back. Within weeks, Page and Jones had ditched the New Yardbirds moniker and come up with Led Zeppelin. The name was inspired by a comment made by Who drummer Keith Moon when they had jammed with the Yardbirds guitarist Jeff Beck and pianist Nicky Hopkins on “Beck’s Bolero” two years earlier. “This will go down like a lead balloon”, said Moon.

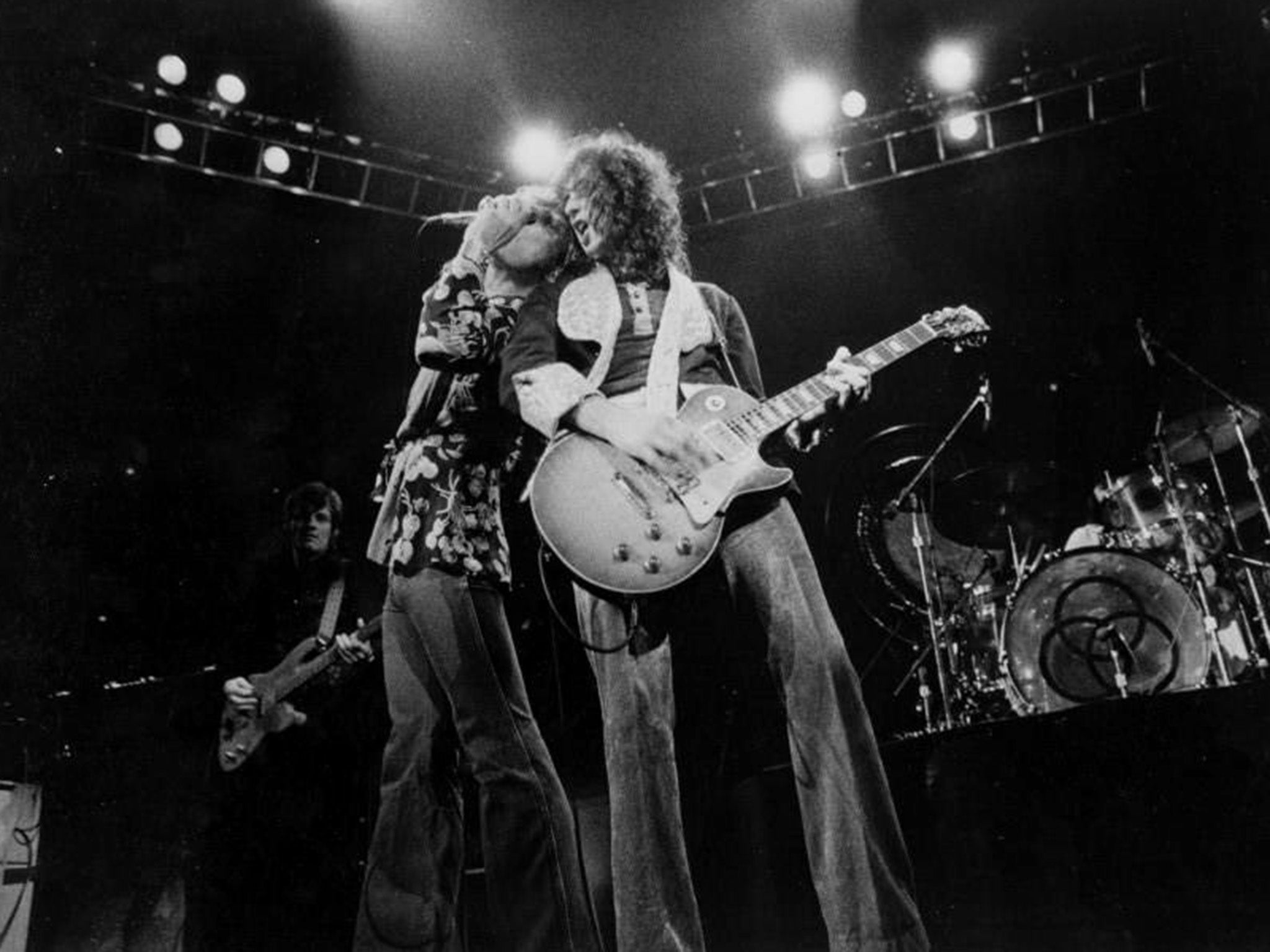

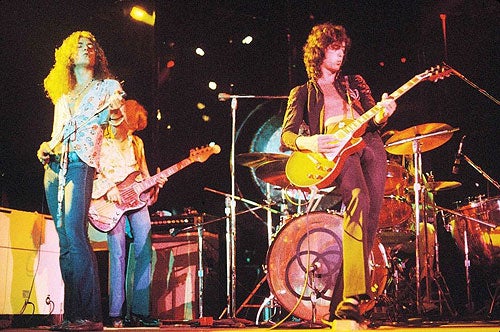

By the time they returned to the States in the spring of 1969, they were topping the bill and recording their second album on the hoof. As their popularity grew, they headlined stadiums, travelled by private plane and created mayhem wherever they went, with many a tale of groupie debauchery passing into rock lore.

They also became the most bootlegged band of all time. Peter Grant, their formidable manager, used to scour the audience for recording devices, and made the occasional baseball-bat-assisted intervention in record stores selling pirate recordings. Page has remained fiercely protective of their catalogue and amassed his own collection of bootlegs, which proved handy when he began considering the current, definitive, state-of-the-art, expanded reissues.

“I made it my business to see what was out there, especially with this project. This stuff hadn’t come out on bootleg because it had been so carefully guarded,” says Page. “Because I was the producer from day one of Led Zeppelin all the way through, I had more points of reference than anyone else... The prospect of being able to do a companion disc to each of the originals, to give the fans what they wanted and more, was so attractive. On Physical Graffiti, there’s an early stage version of “In the Light”, you’ve got the structure of it, and you can hear the additional work that went into it.”

This approach is commensurate with the fact that, back in the Seventies, Led Zeppelin didn’t release singles in the UK. Indeed, by 1974, they’d assumed even greater creative control with the launch of their own label, Swan Song Records. They hit the ground running with the eponymous debut by Bad Company and Silk Torpedo by the Pretty Things but, as Page proudly recalls, “Physical Graffiti was the first piece of Led Zeppelin product on our own label, the right album for the right time. We had material that was left over from the fourth album and needed to be heard. Other people had done double albums and I was really keen to do a double showing all that we were capable of, from the sensitive guitar instrumentals through to the density of something like “In the Light” and the urgency of something like “In My Time of Dying”. Every track has its own character.”

Indeed, many consider Physical Graffiti, with its lavish, fenestrated cover and breadth of styles, the pinnacle of Led Zeppelin’s output. They would not be as carefree again. After a car crash in Rhodes in the summer of 1975, Plant was in a wheelchair when they recorded Presence. Two years later, the singer’s first-born son Karac died of a stomach infection. The making of In Through the Out Door in 1978 was overshadowed by Bonham’s struggle with alcoholism and Page’s battle with drug addiction.

And then John Bonham died in September 1980, putting an end to the last chapter of their stellar career. Page, Plant and Jones have reunited three times since, for Live Aid in 1985, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Atlantic Records in 1988, and to pay tribute to Ahmet Ertegun in 2007, but these, as well as the two albums Page and Plant made in the Nineties, have been mere postscripts.

While Plant has forged on as a solo performer and the frontman of the Sensational Space Shifters, the guitarist has struggled to find partners on his wavelength, despite collaborations with Paul Rodgers, David Coverdale and the Black Crowes. He talks wistfully about doing his own thing “towards the end of the year. Not anything you’d imagine I’d ever do. I’m warming up on the touchline. I know what’s coming next, the fans do not and it’s nice to surprise them,” he muses, as much about the reissues as about his next venture. “It’s been fun. We didn’t repeat ourselves, we went over the horizon in every direction. There are so many tangents, so many facets to the Led Zeppelin music. We were not a one-trick pony.”

Unlike many of the groups they inspired, Led Zeppelin were a versatile, ever-changing outfit, with Page as likely to strum a mandolin or a 12-string acoustic as to attack a twin-necked guitar with a violin bow before plucking another killer riff from thin air.

How does he feel about their legacy? “Some bands have done terrible things, some bands have done really good things, playing in the spirit of Led Zeppelin. You’re only passing on the baton really. What does matter is that we’ve managed to make a difference and quite clearly Led Zeppelin’s music did.”

‘Physical Graffiti’, including a disc of previously unheard material, is released on 23 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments