Ian Steel: Cyclist who broke new ground for UK racing by winning the gruelling Peace Race in Eastern Europe

'His Peace Race win never got the acknowledgement it should have'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With Olympic, World Championship and Tour de France glass ceilings shattering in the last 10 years of British cycling, it is all too easy for previous historical landmarks, like Ian Steel’s breakthrough victory in the 1952 amateur Peace Race in Czechoslovakia, to be forgotten.

However, it’s also true to say that the East European victory for Steel both took British road-racing to unprecedented heights, and indirectly shaped it for generations to come.

“His Peace Race win never got the acknowledgement it should have,” Brian Robinson, a cycling pioneer who became the first British rider to clinch a Tour stage, in 1958, told The Independent. “But that was his greatest moment of his great year.”

Up until Steel’s win, British cycling had been a thriving but inward-looking community, its riders barely racing across the Channel. It was also hamstrung by exceptionally bitter divisions between its two main organisations, the National Cycling Union (NCU) and the breakaway British League of Racing Cyclists (BLRC).

And even before Steel’s BLRC-backed squad had headed for Warsaw, and what would be the British debut in a gruelling 1,326-mile race through Poland, Germany and Czechoslovakia, they were reminded that they were heading into uncharted waters when consulate officials warned, “If you go over there on a British passport, then we wash our hands of you.” Soviet bloc authorities were hardly more sympathetic towards participants from a country considered the closest European ally of the US; the event had been specifically created in 1948 for the greater glory of post-war communist sporting values – and to strengthen unstable Warsaw Pact alliances. Feelings were so sour, local media later claimed – falsely – that the six had been asked to work as British spies whilst racing.

Seeing the 100,000 capacity crowd for the Peace Race opening ceremony in Warsaw’s national stadium, and the formal greeting by top Red Army general Konstantin Rokossovsky, made the importance of the event to Eastern Europe quickly dawn on Steel and his team-mates. (Their spirits were high, too: realising that Rokossovsky could not speak English, the GB team welcomed him with a cry of “Bollocks”.)

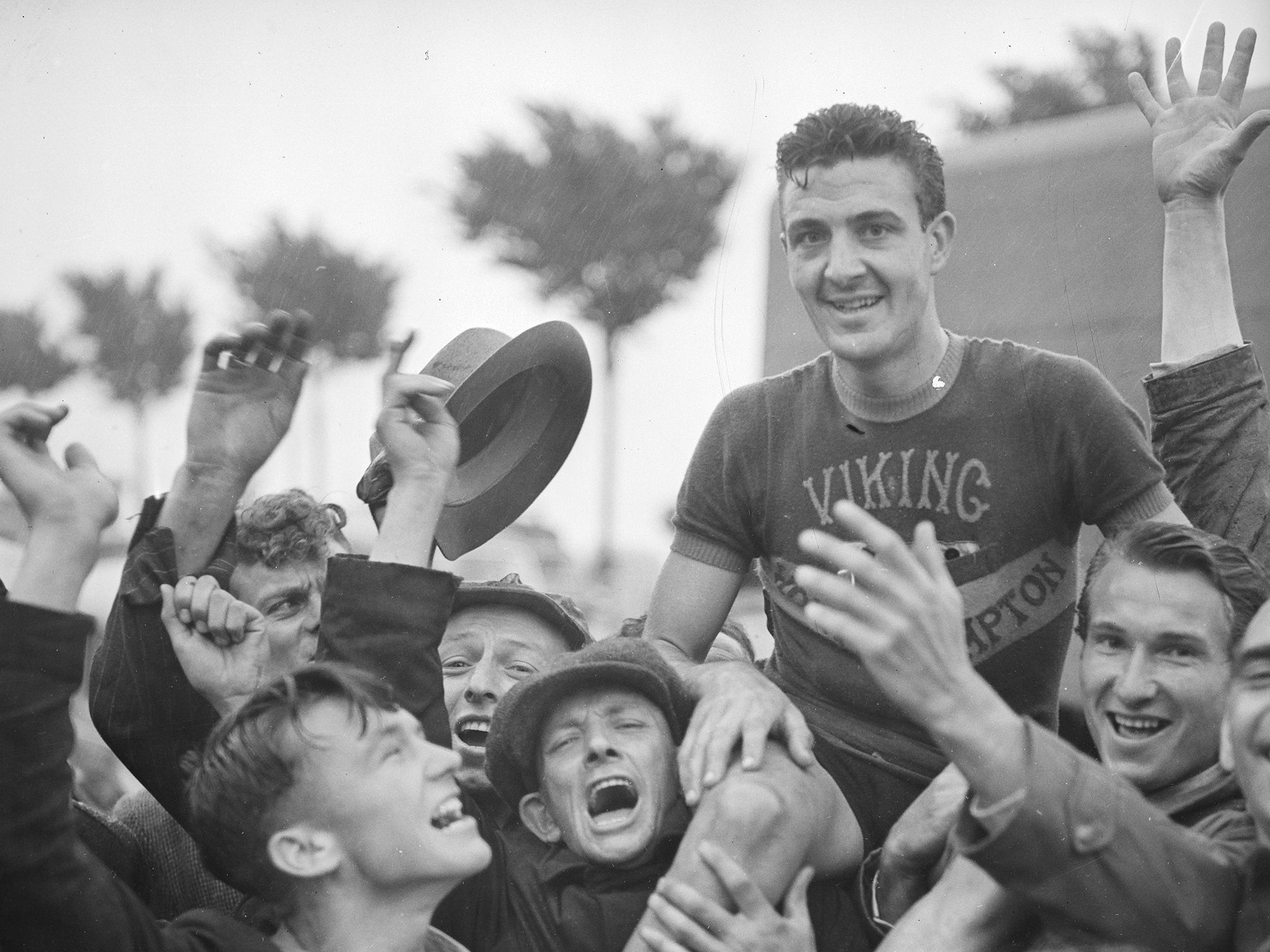

Courageous attacking over the Ore Mountains eventually allowed Steel to win outright ahead of local favourite Jan Vesely, in front of 200,000 presumably disappointed Czech fans in Strahov Stadium. The team were refused clean jerseys for the winners’ podium ceremony by the disgruntled organisers, as well as the chance of doing a lap of honour – and their top prizes of a Tatra car and motorbikes were never delivered, either.

Steel’s win in what was by far the world’s hardest amateur race garnered no UK media coverage barring the Daily Worker and a few paragraphs in Reuters. Cycling, then Britain’s leading specialist publication – and as a stalwart NCU supporter, with no time for BLRC success – gave it all of 12 words.

However, the impact on the grassroots scene of the victory – at the time a British rider’s greatest ever road victory in mainland Europe – was huge. Equally importantly, Steel’s Peace Race win and the realisation that a wealth of similar talent was probably being stifled by the NCU-BLRC rivalry galvanised cycling’s governing body, the UCI, into pushing the two organisations towards eventual unification as the British Cycling Federation – today’s British Cycling.

Interviewed in the GB cycling history book Kings of the Road, Steel himself said “It was the turning point. It needed something like my win to make that happen.”

Steel himself had already had one previous highpoint in his career, when he won the 1951 Tour of Britain by more than six minutes – aged just 23. Steel, who had started riding a bike as a messenger boy in Dunoon, in western Scotland, was hailed as Britain’s best road racer of the time. It also netted him £120, the equivalent of three months’ wages in his job as a carpenter.

As a professional, though, Steel failed to shine, with the low point coming in 1955 when he was part of Great Britain’s first ever Tour de France team – and abandoned mid-race. “He wasn’t the Ian Steel we’d expected,” says Robinson. “He hadn’t been training in France since January like the rest of us, and he paid for that.” Outside the Tour, Steel’s Viking team were rivals to Robinson’s Hercules squad, and Robinson – backed by a majority of Hercules riders in what was a national team – recollects that “he felt a bit left out.”

That April, Steel had also been part of Great Britain’s first ever Grand Tour team, in that year’s Vuelta a España, but one by one the riders abandoned due to appalling racing conditions. “It was bloody miserable,” recollected Ian Brown, his team-mate there. Steel earned praise from overall winner Jean Dotto for his gutsy racing on one climb near Barcelona. “He was tearing us to pieces,” Dotto said later. But Steel abandoned, apparently due to loneliness after all his team-mates had already quit.

After another abandon of the Vuelta in 1956, Steel quit as a pro aged just 27. But the effect of his Peace Race victory remains. As Cycling, ironically enough, wrote in an editorial in 1967, “If Steel had been born 10 years later he might today be one of the world greats; as it was, he paved the way, proving it was possible for a Briton to match the Continentals. For that, British cycling will be forever indebted.”

Ian Steel, cyclist: born Glasgow 28 December 1928; died Glasgow 20 October 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments