First moon landing: Michael Collins was the 'forgotten astronaut' - but he played a vital part in the Apollo XI mission

Rupert Cornwell on the nearly man who turns 85 today

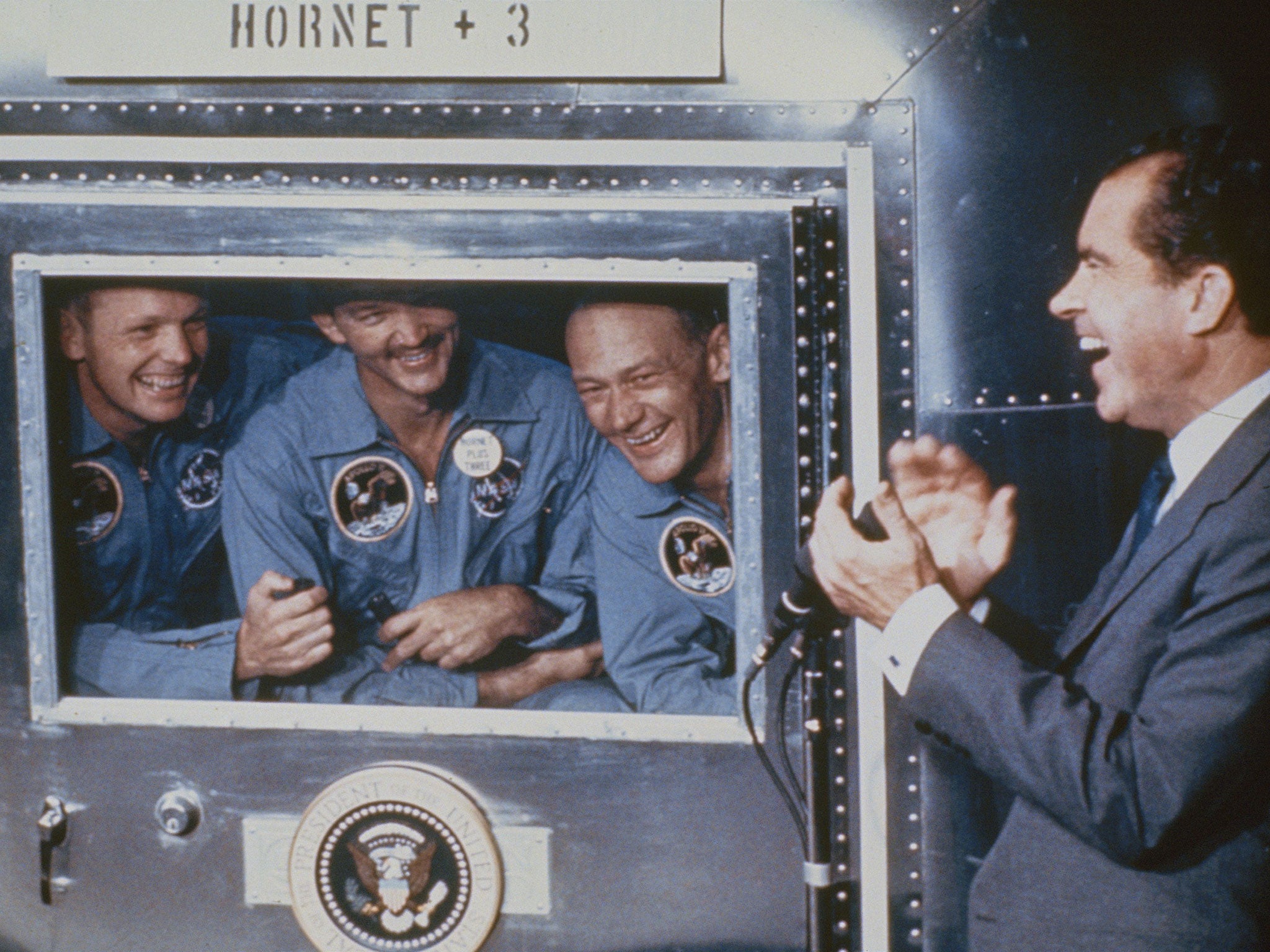

He has been called the forgotten astronaut – the odd man out in the most spectacular technological feat of the 20th century, with the humdrum job of merely flying the command module on the Apollo XI mission, while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin reaped the glory of being the first humans to set foot on the moon.

But Michael Collins played an equally vital part, thanks to skills honed in thousands of hours of Nasa (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) training by carrying out the docking manoeuvres that allowed the lunar module first to detach from the mother ship, and then link up with it again, after it ascended from the moon's surface.

That day in July 1969 he had an experience which was his alone. His two colleagues departed, the command module hurtled across the dark side of the moon. All contact with Earth, as well as with Armstrong and Aldrin, was lost. Suddenly he was the most solitary person ever. Collins wrote in his 1974 memoir Carrying the Fire – widely considered the best book ever written by an astronaut – “I am alone now, truly alone… and absolutely isolated from any known life.”

By his own reckoning he could still have made it to the moon's surface, under Nasa's rotation system, as commander of the final moon mission, Apollo XVII, in 1972. But six months after Apollo XI's mission, he left Nasa. As he put it, “My mindset was, 'It's over, we did it'.”

Collins's path to the moon mission was fairly standard: military college (in his case West Point), then service as a test pilot, before becoming one of the group of astronauts selected by Nasa in October 1963. Three years later, he was pilot on the Gemini X flight, the last in the programme that paved the way for Apollo. Less standard was his life in “retirement.” For seven years he was director of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, before studied advanced management at Harvard and embarked on a successful business career.

Inevitably Collins is forever linked to the moon: an asteroid and a lunar crater are named after him. But his sights are more distant. “Nasa should be renamed Nama,” he during a 2015 talk at MIT, where he occasionally lectures. “They ought to make [Mars] their one overriding goal and destination.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments