Edith Cavell: 100th anniversary to mark death of World War I nurse revered in Britain

Belgians recall her bravery in treating soldiers from both sides of the conflict

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Revered in Britain for her courage, First World War nurse Edith Cavell is now a forgotten figure in Belgium, the country where she was executed for treason.

Monday will mark 100 years since German soldiers shot Cavell at a Brussels shooting range, an act seen at the time as a shocking affront to human decency. The anniversary will be remembered at ceremonies across the UK, from Inverness to Norwich, as well as Canada, where she gave her name to the 11,000ft Mount Edith Cavell. Earlier this year, the Royal Mint issued a £5 coin depicting her tending a wounded soldier.

Yet few Belgians recall her bravery in treating soldiers from both sides of the conflict. In Brussels, Edith Cavell is best known for giving her name to a prestigious hospital that is on the site of the nursing school she helped to set up. The local Belgian press has largely ignored the centenary, despite Monday’s long-planned unveiling of a new bust by Princess Anne and Belgium’s Princess Astrid in the Parc Montjoie, which adjoins Edith Cavell Road and is close to the Edith Cavell Hospital.

There will be other centenary events, but mostly run by the local British community. The Belgian Edith Cavell Commemoration Group, set up in 2010 by retired businessman Andrew Brown, has helped to organise exhibitions and concerts, but has struggled to raise awareness of her legacy. “I was disappointed that she was not more recognised,” he said. “They don’t commemorate as much in Belgium as they do in Britain.”

Mr Brown admits he first heard about Edith Cavell when, as an Ernst & Young accountant, he was assigned to tell the hospital it was bankrupt. (It closed in 1982, but Mr Brown was instrumental in its reopening the following year.) The experience inspired him. “The legacy she left us is one of teaching and caring,” he said.

Sophie de Schaepdrijver, a First World War historian and professor at Pennsylvania State University, says that if Cavell is unknown, it is because Belgium has largely forgotten about the war. “Belgians were for a long time complacent and smug towards the wartime generation,” she said. “In my four years studying modern history at Brussels Free University, we did not touch the war at all.”

Born in Norfolk in 1865, Cavell went to Brussels in 1906 where she was eventually appointed matron of the Berkendael Surgical Institute training school for nurses. On holiday in Norwich when war broke out, she quickly came back to Brussels. Cavell tended both German and allied wounded, and refused to leave her post when Brussels fell.

However, she also worked with the Belgian underground network to help to smuggle more than 200 British, French and Belgian soldiers into the Netherlands. The soldiers were given fake identification and hidden until they could make it to the Dutch frontier.

In August 1915, Cavell was arrested for treason. She confessed her role, and was condemned despite appeals from then neutral United States, as well as Spain and the Vatican. Taken from the Saint Gilles prison at dawn and transferred to a firing range in the Schaerbeek, she was shot by a 16-man firing squad, while still wearing her nurse’s uniform.

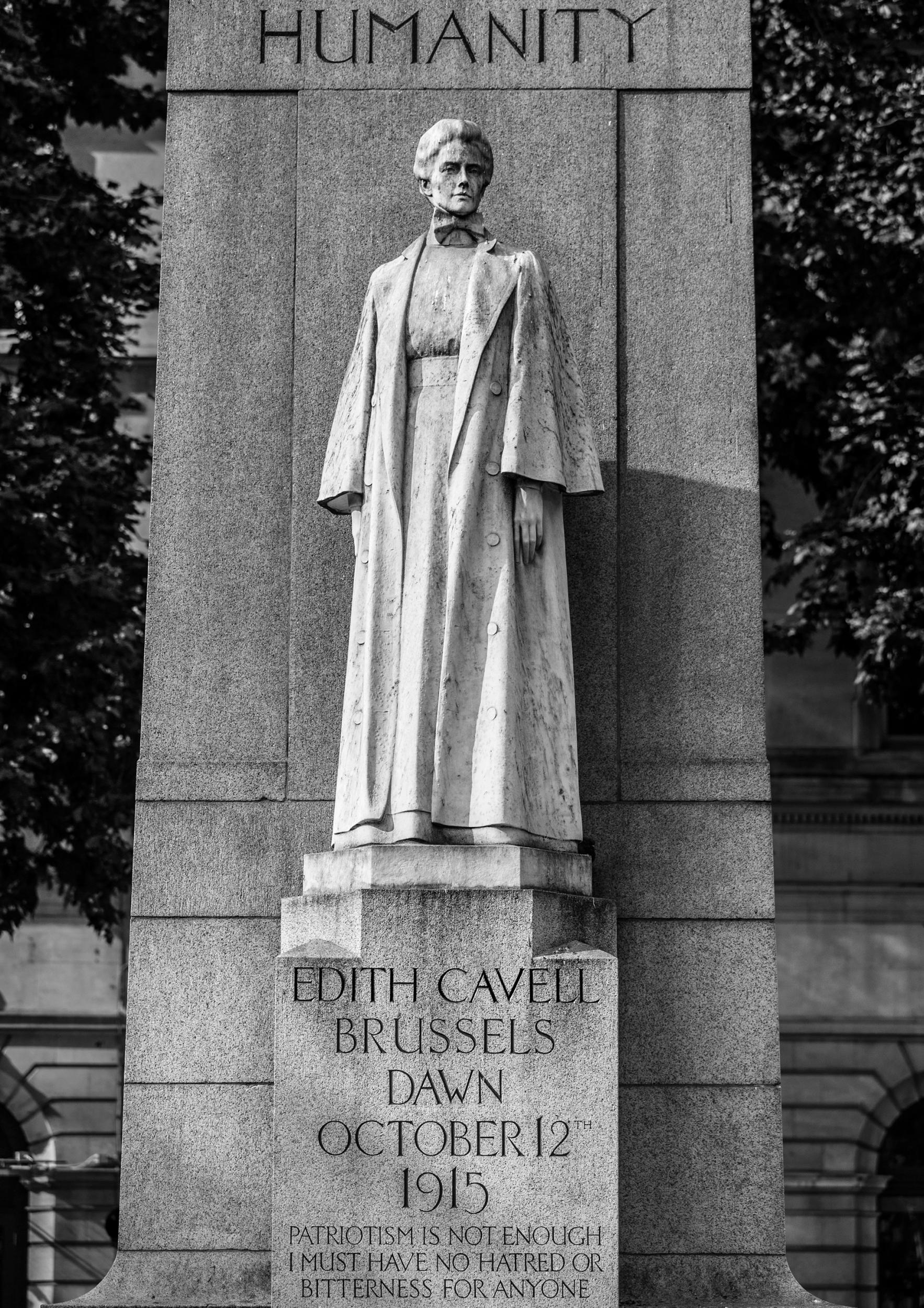

However, her execution was a propaganda disaster for Germany. Cavell was hailed as a martyr and the Germans as murderous monsters. In the eight weeks after her execution, recruitment into the British army doubled. Her death was equally mourned in Belgium, where King Albert I said: “Brussels will be haunted for ever by the ghost of this noble woman, shamefully murdered.” Many memorials were raised in her memory, the most famous being her statue in St Martin’s Place, next to Trafalgar Square.

In France and Belgium, Edith became a popular name for girls, including the singer Edith Piaf, born just two months after the execution. Cavell’s remains were brought back to Britain in 1919 and she was given a state funeral and a memorial service in Westminster Abbey attended by King George V, before being reburied in Norwich.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments