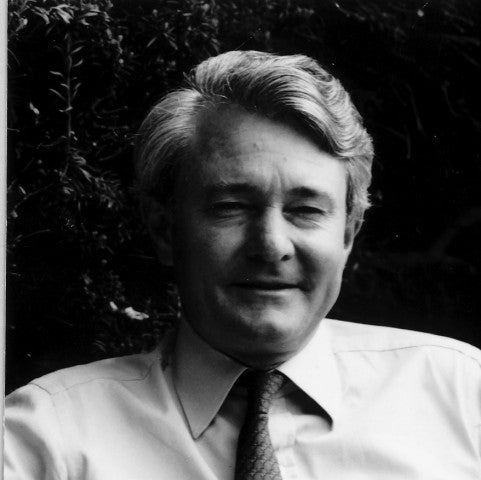

The Earl of Leicester: Landowner who took charge of Holkham Hall in Norfolk and restored both house and estate to former splendours

Leicester was an extremely hard-working servant of his county

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By any reckoning Holkham Hall in north Norfolk is one of the loveliest great houses of Europe, and its surrounding estate one of the best-managed in Britain. Its current pre-eminence owes much to the love and care of Edward Douglas Coke – Eddie – the 7th Earl of Leicester, a dynamic Southern African who came to Britain at the age of 25.

Along with Merlin Waterson, at that time the National Trust Historic Properties Director, my wife and I were given a two-hour tour of Holkham, when Eddie Leicester was a spritely 72. Two recollections are etched in my memory: first, the wonderful collection of paintings and treasures; and the non-deferential warmth with which he was greeted by guides, custodians, volunteers and others working there. The discerning people of Norfolk knew they owed him for having reversed the decline of both the mansion and the estate.

It was typical that he should hand over to his son Tom, Viscount Coke, in 2005, when he was still young and energetic. It was also typical that he should have had a portrait commissioned and displayed of those who had worked for him for many years. "Like me," he told us, "they are custodians of Holkham."

Edward Douglas Coke was born in Zimbabwe, then Rhodesia, and brought up on a farm, far from any city. This gave him an understanding of the problems he was to encounter in the rural North Norfolk of the 1960s. "From a very early age it was imbued into me that one day the responsibilities of Holkham would be mine."

His father, Anthony Lovel Coke, having been expelled from Gresham's School, Holt, was despatched to Bechuanaland, now Botswana, to get himself "sorted out". He did so – but to the family's consternation the "sorting out" resulted in a life devoted to Southern Africa, to the detriment of the estate in Norfolk. In 1962, when Eddie came to England, Holkham, house and estate, was in a sad way. Though he did not succeed the title until 1994, he was de facto in charge, as his father spent his time in Africa.

I first heard of him from an unlikely source. Edwin Gooch, President of the National Union of Agriculture Workers and MP for North Norfolk, told me the landowners in his constituency were "a pretty feudal lot", but, he added, there was "a South African lad who has inherited the greatest estate of all, Holkham" who he liked, and who seemed sincere about improving the conditions of NUAW members.

Gooch was prescient. In 1964 Bertie Hazell, an NUAW official, was elected to North Norfolk. Conservative Norfolk was not best pleased, but Leicester went out of his way to make a friend of Hazell and seek his advice.

In 1965 I was on the Agricultural Miscellaneous Bill Committee. Hazell, who had campaigned on the issues of tied cottages and agricultural rents, told us there would be little difficulty if all landowners were like Coke, who was installing bathrooms in 370-odd cottages on his estate and making provision for retired workers. "The boy is a chip off the old block," he said – the old block being the 18th century agricultural reformer, Coke of Holkham.

After Hazell lost his seat in 1970 Leicester continued to seek Hazell's advice and wisdom arising from his 30 years' membership of the Agricultural Wages Board.

Therein lay the key to Leicester's success. He would seek advice from the best possible source, then act on that advice. Merlin Waterson was fascinated by the way in which he would identify and seek out the most authoritative experts. He was not just vaguely enlightened: he took determined, serious-minded, practical action, always with a view to the long term.

If it was an architectural problem Leicester would go to John Cornforth, architectural editor of Country Life and a pivotal member of the Historic Buildings Council. If a decision had to be made on textiles he would go to Sheila Stainton, Housekeeper of the National Trust. The result was that a great House, on the verge of dereliction in 1962, is now a House whose care is exemplary.

Leicester was similarly adept in picking the brains of international scholars. He not only set the standard for great houses; but for estates too. He commissioned Susanna Wade-Martins to write a history of the estate and its structures in their 18th and 19th century heyday. Leicester was an active Trustee of the Norfolk Historic Buildings Trust and ally of the ebullient Billa Harrod, champion of Norfolk churches.

Leicester was an extremely hard-working servant of his county. Baroness Shephard, education minister from 1994-97 and MP for South West Norfolk from 1987-2005, recalled to me that he had been a "fresh eye" as member of the King's Lynn and West Norfolk Burgh Council (1973-91), its Leader (1980-85) and Chairman of its Planning Committee (1987-91),

Nationally – unglamorous but hugely important to Eastern England – he was President of the Association of Drainage Authorities, which brought him into fruitful contact with the MP for Huntingdon, John Major. He was also President of the Ancient Monuments Society, and their Secretary Matthew Saunders told me, "Leicester restored the Main Hall of Holkham, one of the most spine-chilling architectural experiences in Britain. Though outwardly mechanical in feel, the poetry was still there. He chaired our AGMs with good humour and presence, devoid of pomposity. He offered his benignly managed estate for experimental purposes: for example, he paid for the upkeep of the hotel/pub in the middle of Holkham village, which had served his 18th century ancestors as accommodation for their guests. It still functions after three centuries."

As Commissioner for English Heritage he was able to cope calmly with his Chairman, Sir Jocelyn Stevens, even when he was hurling typewriters out of windows in one of his rages. But perhaps his most significant service on the national stage was as an effective Chairman of the Historic Houses Association. Peter Sinclair of the HHA told me that he was their oldest President but among the most energetic.

In 1998 Leicester did more than anyone else to persuade the incoming Labour government to delay restrictive taxes on stately homes. He provided facts and figures to identify the heritage's contribution to tourism and regional economics – two causes of which he was such an effective champion.

TAM DALYELL

Edward Douglas Coke, 7th Earl of Leicester, landowner and public servant: born Rhodesia 6 May 1936; married 1962 Valeria Phyllis (divorced 1985; one daughter, two sons), 1986 Sarah de Chair; died Norfolk 25 April 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments