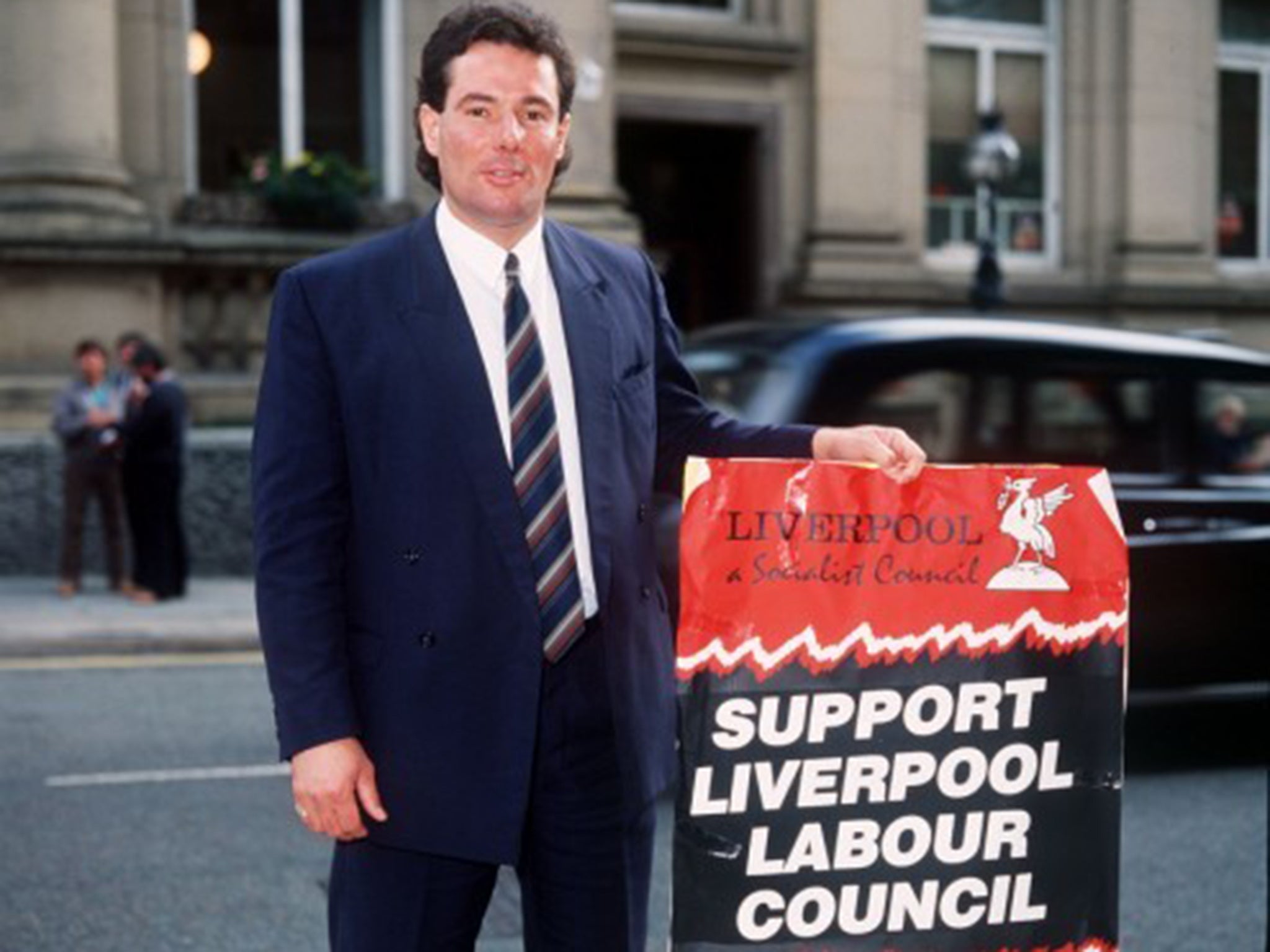

Derek Hatton: Meeting Liverpool's socialist poster boy after hating him for 30 years

Jane Merrick received a plea from Derek Hatton to put his side of the notorious events that nearly broke her family, the Labour party and the city of Liverpool

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Derek Hatton has just speared the yolk of an egg with his fork, and is watching it ooze over a plate of chargrilled asparagus. The former Militant leader, poster boy of 1980s socialism, is talking about his old enemy Neil Kinnock, who drummed him both out of office in Liverpool and out of the Labour Party. “Luckily I’m the sort of person in life who doesn’t bear grudges. I’ve always felt if you’ve got a grudge with somebody, either they don’t know you’ve got a grudge on them, or they don’t care. So the only person that gets ripped to bits is you.”

That may be Hatton’s view, but I struggle with it. I have been harbouring a grudge for 30 years. It hasn’t “ripped me to bits” but comes and goes, like a stomach ulcer, and now that the far left is back in fashion with Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, the pain is acute. My grudge is against the man who is sitting half a metre away from me in The Restaurant Bar and Grill, near Liverpool’s town hall. This is the first time we have met, yet as Hatton haunted my childhood like a bogeyman or mythological monster, it is like coming face to face with someone I already know. And I am here to tell him why I hate him.

In September 1985, when I was 11, Hatton sent redundancy notices to 31,000 council workers in Liverpool. One of those workers was my mother, an English teacher at a comprehensive school. The letters were despatched by a private hire cab firm. It became the climax of a war of attrition between the Militant-run council and Margaret Thatcher’s government. The incident gave Kinnock, then Labour leader, the ammunition to root out the hard left from Liverpool, inspiring his most famous speech, at the k Labour party conference in Bournemouth 30 years ago this week, in which he accused Militant of the “grotesque chaos of a Labour council – a Labour council – hiring taxis to scuttle round a city handing out redundancy notices to its own workers”. As Kinnock spoke, Hatton shouted “Liar!” from the back of the hall, prompting the Labour leader to address his adversary directly: “I’m telling you, and you’ll listen – you can’t play politics with people’s jobs and with people’s services or with their homes.”

This marked the very moment when, through Kinnock’s electrifying declaration of war against Militant, the Labour Party began its long 12-year walk back to electability. Watching the footage on the 6 o’clock news in our semi-detached home in the Liverpool suburb of Aigburth, it felt like our city, which was being sunk by torpedoes from left and right, the Militant council and the Thatcher government, had suddenly been thrown a life raft by Kinnock. As much as Hatton and his allies claimed at the time they were never going to carry out the redundancies, the instability meant that many of those workers – particularly those in NUPE, Nalgo and my mother’s union, the NUT – feared they would be out of their jobs in the run-up to Christmas. My Labour-voting parents (my dad was a teacher in the neighbouring authority of Knowsley) felt like pawns in a dangerous game of brinkmanship between Hatton and Thatcher, and betrayed by their own side.

Hatred sown at the age of 11 grows deep roots, particularly when it is directed towards someone who you feel is attacking your mother. In 2013, when Thatcher died, Hatton went on TV to say he wished she’d never been born because of what she did to “our” city. Enraged, I wrote an article saying that while Thatcher had left Liverpool to rot, Militant’s behaviour had compounded the decline. Hatton must have read this piece at some point as, during the election campaign in April this year, he contacted me via Twitter to suggest we meet up for a “proper discussion” about what happened in 1985. At first I refused, but after Labour lost the election (and before Corbyn had even announced his candidacy), Hatton reapplied to join the party that had expelled him in 1986, and I was intrigued. Why was the man who had been so ruthless about the lives of tens of thousands of his fellow Liverpudlians now seeking me out for absolution?

On a bright sunny day in September, I am breaking bread with the man I’ve hated for three-quarters of my life. At 67, Hatton no longer has the boyish, cocky face that I remember. Yet he looks very fit for his age, suntanned and dressed in jeans, with a dandyish spotted handkerchief spilling out of his breast pocket. Affable and charming, he tells me got in touch for two reasons: first, to set the record straight about 1985, and second because, incredibly, he doesn’t want anyone to think he is a bad person.

There are signs of prosperity in this Liverpool restaurant: a heavily tanned woman on the adjacent table wears gold jewellery and sips champagne. But Hatton swiftly transports me back to 1984, when the city was already in a battle with the government over industrial disputes at the docks. He tells me he was in a TV green room with Teddy Taylor, the Tory minister and one of Thatcher’s closest political allies, who said to him: “Just remember Derek, Margaret’s taking on the miners and when she’s finished with them she will come for you, so don’t get too confident.”

Hatton tells me it was this remark that hardened his feeling of “it’s them or us”. He comes alive as he recalls the summer of 1985 when his council refused to set a budget and ran up an illegal deficit. At one meeting of council officials, Hatton says, “The city treasurer turned round and said ‘you will either have to cut services or lose jobs’. And I said ‘how many?’ He goes ‘I think you would have to cut every one’. We all looked at each other and all of a sudden I said, ‘What if we did that and then afterwards didn’t carry it out? OK, let’s do it’. ” It was a high-stakes ploy to call the government’s bluff and get Thatcher to bail out the council.

My head is reeling from this first-hand account of how they hatched the plan. The “vast majority” of union leaders in the city agreed with the plan, but he admits: “However much we were sure that the redundancy notices were not go ing to be carried out, nonetheless it’s still a redundancy notice and there will be that panic.”

Nalgo, NUPE and the NUT did not believe the reassurances and refused to hand the notices out to their members – hence the taxis. “Every Friday night I used to get all the minutes and the agendas for next week’s meeting brought round either by a council car or by a Davy Liver taxi … So it was exactly the same thing.”

While he is still slick, and his mind as quick as it ever was, he is full of contradictions. Despite claiming he never bears grudges, he can’t hold this line for long: “I dislike what Kinnock did more than I dislike what Thatcher did. I expected it of Thatcher, you don’t expect it of a Labour leader. It’s taken 30 years to start to realise that it is worth having a decent Labour party again.”

But talking about my mother and all those workers, there is the hint of contrition. “If I had the time again… I probably would say I wish I could’ve communicated with more people. I wish I could’ve been in a position where more people were being talked to like I’m talking to you, but you can’t get round 31,000 people.

“Of course we could have carried out the cuts. Yes, we could have not built the houses. But I walk in town now and I get people who will stop me and say either ‘You got my mother a house, thank you very much’, or someone who says ‘My dad has only just retired now after 30 years in the job’.

“Even now 30 years later I want to put the record straight. I have a great relationship with people here, but still the powers that be say that Derek Hatton in that era was like the elephant in the room... so I get a little bit upset about that sometimes.” It is gratifying to know that he gets upset, even if it is only for himself. In any case, the “powers that be” in the Labour party are now Corbyn and his allies.

Hatton paid his £3 as a registered supporter, and would have voted for Corbyn, whom he describes as “fresh and new” – but never got to vote because he remains expelled. “The irony is that even though I haven’t got a ballot form, I’ve had so much of a say over the past two months, on every single political programme going… it doesn’t really matter any more.”

While it would seem barely believable six months ago, Hatton sounds tempted to relaunch his political career, perhaps as an MP or mayor of Liverpool. “I’ve got a massive ego – of course my ego has said, why don’t you stand against Joe [Anderson, the city’s mayor], but my head says, you’re 67 years old, you’ve got a great life, you’ve got four children and 11 grandchildren. I’ve got a couple of employee benefits companies, the big one is the Bike 2 Work scheme [of which he was a co-founder and is a director]. I promise you my head will always win, but you should never say never.”

So does he want my forgiveness? Hatton laughs: “It’s not about forgiveness. I certainly want us to walk out of this room today with you understanding more than you did before about why I did it. And actually, I am not all that bad a person. I actually haven’t got horns.” Hatton puts two bent fingers on top of his forehead.

After some photographs by the River Mersey, we part on amicable terms. Hatton is not a monster. I don’t think he is a bad person. But I am still wrestling over whether to forgive him. Back in London I pick up the phone to Lord Kinnock to get the other side of the story. The former Labour leader’s memories are as vivid as if it was all yesterday. He reveals that, in September 1985, when he was already planning to confront Militant at the party conference the following month, he read about the redundancy-by-taxis while on the platform at Preston train station with his then chief of staff, Charles Clarke. Kinnock tells me: “I turned to Charles and said, ‘I have got them, this is it’ .” During the speech, when he got to the passage about Liverpool, Eric Heffer, Labour MP for Liverpool Walton, stood up to walk out.

“Eric Heffer got up to the left of me, I thought he was going to strike me. He was completely in thrall to the Militant Tendency. He hopped up and started walking. I shifted my feet, using my rugby experience, to ensure that I had maximum resistance and mobility. Eric just swept by. As I watched him go I felt quite sorry for him.” k

What does he think of Hatton today? “What he inflicted on the people most affected was awful, unforgivable, as was the damage inflicted on an already crisis-hit city. In one sense Liverpool, a city I love, never lost its vitality.There are more jokes and music and football in Liverpool than anywhere else per square acreage – it never lost that brilliance, but it was obscured by the destructive economic collapse which was as a result of the Militant Tendency.”

“It has taken a generation to overcome that,” Kinnock continues, “to restore the vitality of the city. This is a passage of time which Liverpool shouldn’t have had to endure.”

I can’t let Kinnock go without asking him about Corbyn. Is everything he did coming undone? He won’t comment directly but says: “The awful thing is the amount of time, energy and commitment that I spent dealing with establishing democratic management of the Labour party in that first period of opposition, from 1983-87, I could’ve been attacking the Tories.

“The absolute crucial priority is to oppose the Tories and to develop a rational, progressive, democratic socialist alternative. When the party concentrates on that, Labour wins. Advancement is a permanent duty.”

As I write, Corbyn is appointing his shadow cabinet. I go back to Hatton to ask him, by email, what Corbyn’s victory means for the Labour party. “For the first time since the Eighties we have a clear choice between a Tory party supported by big business, and a Labour party based on the trade unions,” he writes. “This might sound very old fashioned, but it’s simply a return to the obvious split that has always existed. It was artificially camouflaged under New Labour.

“It’s an exciting time for the whole country, but I fear that the pressure which will be brought to bear from the ‘New Labour dinosaurs’ and from much of the media will be massive, and Jeremy Corbyn will need strength and support in abundance in order to resist it.”

It feels troubling to me that, just as I am being forced to disinter the memories of 30 years ago, the hard left has not only come back from the dead but is now in charge. At the very moment that Hatton had sought our reconciliation, his politics have been reconquering the Labour party. While I have decided to no longer hate Hatton, Kinnock is right: Liverpool’s vitality was obscured for a generation. For me it’s not simply about my mother, but that Hatton used his dogma to crush the spirit of our city, my city. Perhaps now I can let the grudge go, but I cannot, ultimately, forgive him. Not yet. Ask me in another 30 years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments