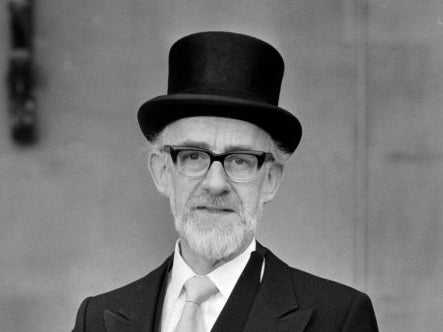

Sir Antony Jay dead: Yes Minister co-writer was both a distinguished product - and critic - of the British Establishment

However, his youthful anti-establishment tendencies evidently mellowed by the time Margaret Thatcher joyfully wrote her own Yes Minister in 1984

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Antony Jay, who died at the age of 86 on Sunday evening, was a prime example of an especially British phenomenon, being both a distinguished product and a distinguished critic of the Establishment. He had been suffering from a long illness, a representative of his family said.

He will always be best remembered for his masterful work in co-writing, with Jonathan Lynn, successive series of Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister in the 1980s, comedies that are ageless in their humour.

Sir Antony's establishment credentials were as impeccable as those of any real or fictional senior member of the British civil service, including Sir Humphrey Appleby, the deeply manipulative bureaucrat in Yes, Minister. Educated at St Paul's School, Sir Antony went on to study Classics at Magdalene College, Cambridge, emerging, naturally, with a First. From there, in common with his generation, he went on to National Service in the Royal Signals. After that, he joined the BBC, where he worked on “Talks”, the forerunner of current affairs, in the early 1960s.

Interestingly Sir Antony's first encounters with the Corporation were during the era of the first great British satire boom, with Private Eye and That Was The Week that Was lampooning politicians and marking the beginning of the end of the age of deference. Sir Antony's early career co-incided with the rise to prominence of David Frost, who, like Sir Antony, had a notably nuanced relationship with the Establishment, though Sir Antony’s satires (much later) were not nearly so vicious as Frost’s early ones could be, while Frost ended up marrying into royalty.

Sir Antony did, though, follow his clever and witty parodies of Whitehall with some very straight scripts for respectful documentaries about the House of Windsor - Royal Family and Elizabeth R: A Year in the Life of a Queen. For these he was awarded the honour of Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO), usually reserved for services to the Queen personally. It followed the CBE he was awarded for Yes Minister.

His youthful anti-establishment tendencies, according to Sir Antony shared with much of the then BBC staff, evidently mellowed by the time Margaret Thatcher joyfully wrote her own Yes Minister in 1984. This she was prompted to do as a fan of their work (not necessarily reciprocated) and when she was asked to present Sir Antony and Lynn with a showbiz award. She claimed it constituted the “first episode of Yes, Prime Minister”, which then duly followed. (Mrs Thatcher, in her only acknowledged venture into fiction, envisaged the abolition of the government Economic Service).

More recently, Sir Antony and Lynn revived Yes Prime Minister in the theatre, for a world of 24 hour news, smartphones and ‘sexed up’ dossiers. By that time the more savage The Thick of It, featuring the magnificently foul-mouthed spin doctor Malcolm Tucker, created by Armando Ianucci, was a more fitting reflection of the times, but the debt of honour to the original Yes, Minister, was plain. The originals, the late Paul Eddington as Jim Hacker, the late Nigel Hawthorne as Sir Humphrey – now the generic name of course for any civil service boss - and Derek Fowlds as Bernard Wooley were brilliantly partnered with Lynn and Sir Antony’s inspired writing. Many of the titles of their episodes from three decades ago immediately bring to mind current political personalities – “Compassionate Society” (David Cameron); “Equal Opportunities” (Harriet Harman); “The National Education Service” (suggested for real only last year by Jeremy Corbyn). As ever with gifted writers, their own words speak for themselves, and rarely has the European project been better summed up than this little exchange in 1981:

James Hacker: Europe is a community of nations, dedicated towards one goal.

Sir Humphrey Appleby: [laughs]

James Hacker: May we share the joke, Humphrey?

Sir Humphrey Appleby: Minister, may I?

[sits]

Sir Humphrey Appleby: Let's look at this objectively. It is a game played for national interests and always was. Why do you suppose we went into it?

James Hacker: To strengthen the brotherhood of free Western nations.

Sir Humphrey Appleby: Oh, really. We went in to screw the French by splitting them off from the Germans.

James Hacker: Well, why did the French go into it, then?

Sir Humphrey Appleby: Well, to protect their inefficient farmers from commercial competition.

James Hacker: That certainly doesn't apply to the Germans!

Sir Humphrey Appleby: No, no. They went in to cleanse themselves of genocide and apply for readmission to the human race.

Maybe Sir Antony’s satire wasn’t quite as gentle as we remember it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments