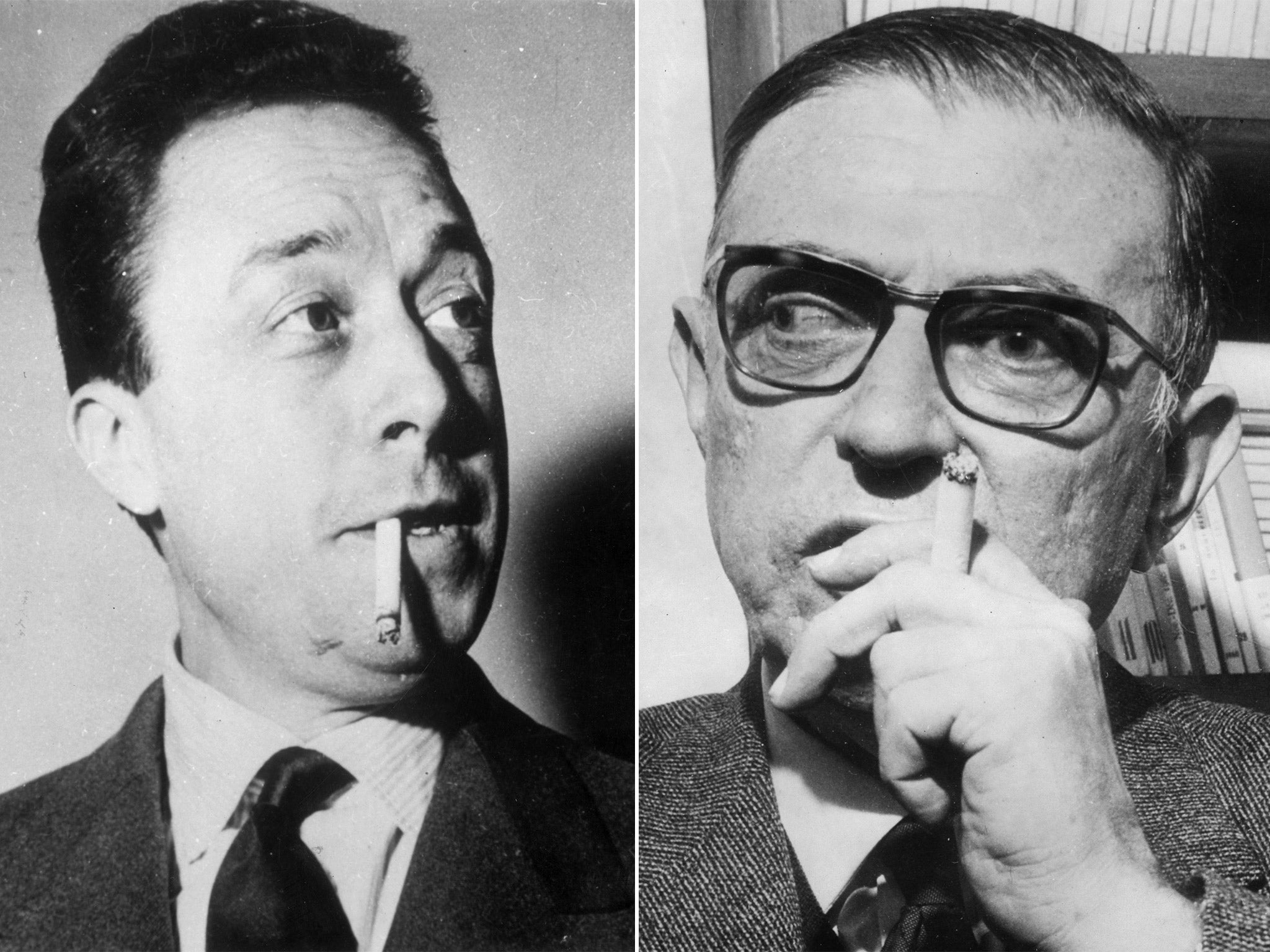

Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre: 'Lost' letter shows philosophers were dearest friends before their bitter falling-out

The pair grew apart in the midst of the Cold War and began to disagree over philosophy and politics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They were France’s chain-smoking philosophers whose relationship turned publicly sour. Indeed, when one of them wrote “l’enfer, c’est les autres” (hell is other people), it was easy to imagine he was referring to his lauded rival.

But now a previously unknown letter sent by Albert Camus to Jean-Paul Sartre shows the two men had been dearest friends only months before they fell out.

The undated letter, authenticated by experts, is believed to have been written in the spring of 1951. “[It] was acquired by an autograph collector in the 1970s and kept in a frame above his fireplace ever since,” said Nicolas Lieng of the Le Pas Sage Bookstore, which specialises in 19th and 20th-century literature. “It was sold to a private French collector, who owns one of the most beautiful Camus collections, a week ago,” he added.

Opening “my dear Sartre”, the long letter signed by Camus, ends with “I shake your hand.” The Nobel-prize winning author of L’Etranger includes a recommendation that Sartre considers an actress named Aminda Valls for his new play. Camus described the actress, who was also a friend of the French stage star Maria Casarès, as a “Spanish republican” and “marvel of humanity”.

At the time, Sartre was preparing to stage his play Le diable et le bon dieu, that was premiered in 1951 in Paris’s Théâtre Antoine. While Casarès got the role of Hilda, Valls did not end up taking part in the production. Camus also makes clear he wrote the letter from his apartment on Rue Madame in Paris’s grand sixth arrondissement, where he lived between 1950 and 1954.

This is not the first time a piece of correspondence between the two intellectual stars of Paris had been discovered recently.

Last year, a short note written by Camus to Sartre in the 1940s shed some light on one of the 20th century’s most infamous friendships. The two men were closely entwined throughout their careers.

They first met during the German occupation of France and become famous overnight when Paris was liberated. They were both essayists, playwrights, literature and theatre critics, philosophers, journalists, and editors-in-chief.

They had the same publisher. They both were awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. Camus accepted his award in 1957. Sartre loftily declined the designation seven years later, claiming to have not been insulted “because Camus had received it before me”.

However, the pair grew apart in the midst of the Cold War and began to disagree over philosophy and politics.

Only few months after the letter, Camus would publish L’Homme révolté that was sharply criticised by Sartre. This caused their bitter and very public falling-out.

Sartre wrote in an open letter: “Dear Camus, our friendship was not an easy one, but I shall miss it,” and accused his ex-friend of “philosophical incompetence”. He also destroyed nearly all of their correspondence.

The rift, in the summer of 1952, divided philosophically minded Parisians.

The two intellectuals never spoke again, although they continued to publicly disagree, in code, until Camus’s death in 1960.

Fifteen years later, the then 70-year-old Sartre, asked about his relationship to Camus in an interview for Les Temps modernes, said: Camus was “probably my last good friend”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments