A journey in grief: We'll meet my daughter Mia again one day, sooner or later, in our own bright places full of love

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

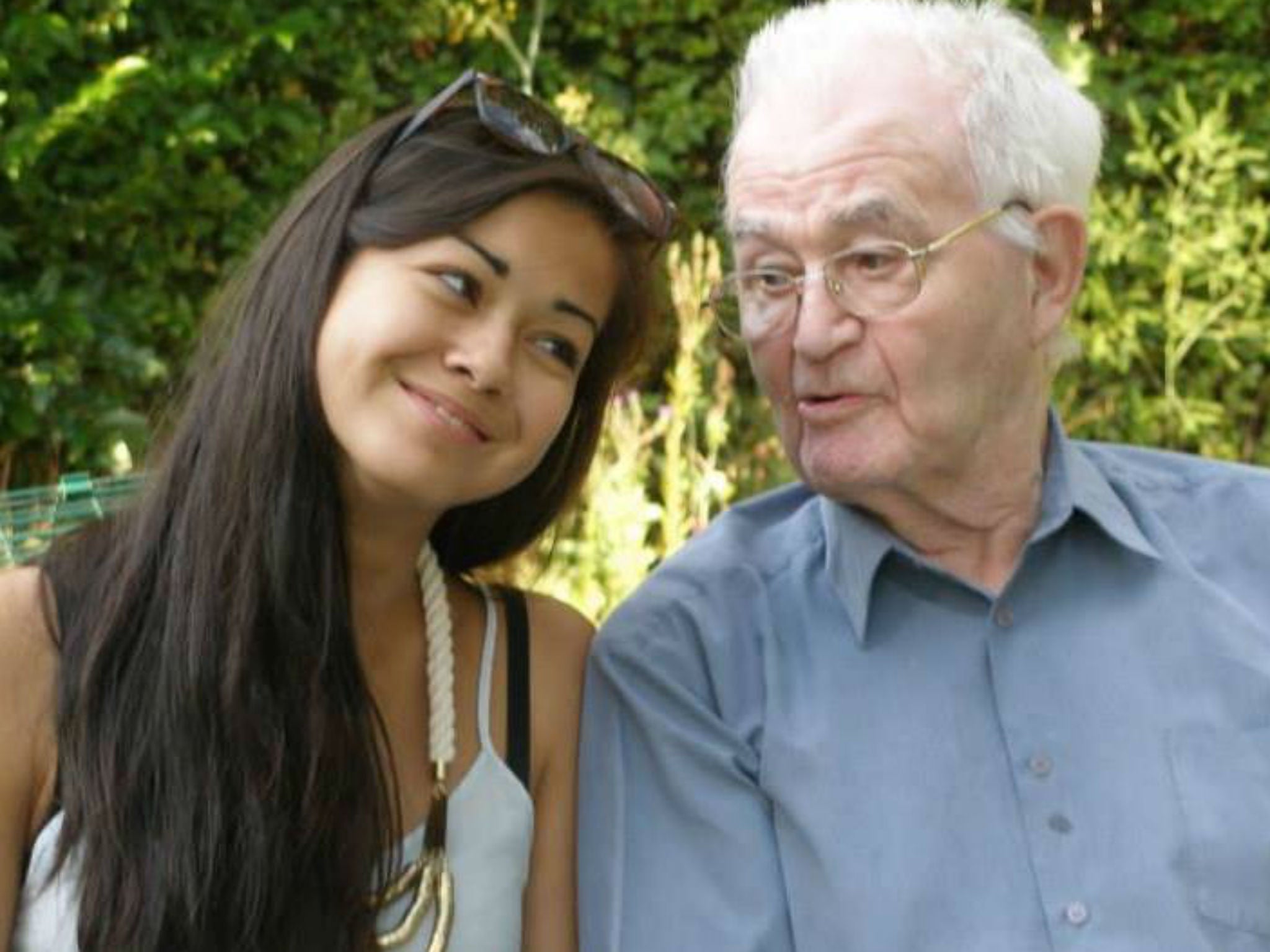

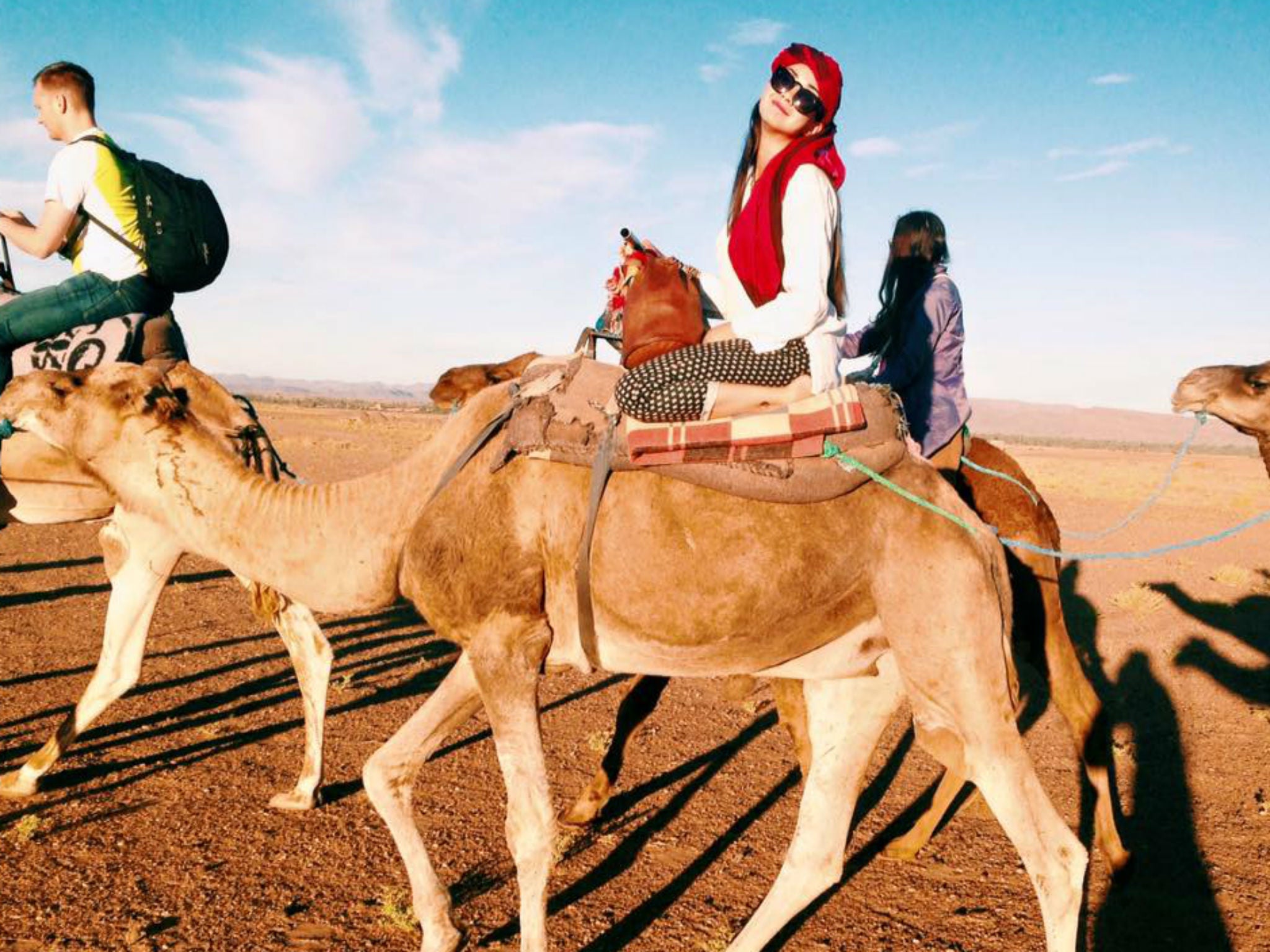

Your support makes all the difference.Mia Ayliffe-Chung is the 21-year-old British backpacker who was stabbed to death in Australia last Tuesday at the hostel she was staying in.

Mia, from Wirksworth in Derbyshire, was working on a farm in Queensland in order to fulfil requirements for her Australian visa.

In the coming week, Mia’s mother, Rosie Ayliffe, will write a daily blog in The Independent as she travels to Australia to collect her daughter’s ashes.

Here, in her own words, she talks about the impact Mia had on people throughout her life.

Mia’s family is raising money to create a fund for charity in her memory. Click here to donate or find out more.

Mia was no angel. Anyone who spent time with her before 11am can vouch for that. She only really became truly human as the day progressed. Her bedroom was so untidy you had to wonder whether it involved health risks. This was particularly galling after we went away on holiday and came back to discover she had kept the whole house immaculate for the duration. She told me a friend had left a used teaspoon beside the kettle and Mia had said to her, 'Are you intending to leave that there?'

Chatty, funny, the ultimate socialite, teachers gave up moving Mia because she was one of those kids who would just make a new friend wherever she sat. And she didn't have a competitive bone in her body. She'd rather lose the race than lose a friend.

But her aura was a captivating one and many of my friends commented on this. When we left London for the sticks, a friend of mine with a long list of qualifications and achievements commented that she was devastated, not because I was going but because I was taking Mia away from her. I was in no doubt that she meant it. Mia was six.

Mia wanted to move up to Derbyshire, but not without her beloved friends. In one school day she had six children lined up at the gate of Clement Dane's school with their coats on and bags packed. A couple of them were quite vulnerable children, so staff were most concerned when they realised the children had intended to slip out of the gate into the streets of Soho and hitch hike up to Derbyshire to live with Mia. One understandably cross mum questioned her daughter.

'If Mia told you to jump out of the window, would you?'

'I didn’t!'

'What do you mean you didn’t?’

‘She did ask me to jump out of the window, but I didn’t!'

And thus terminated a beautiful friendship. I explained years later why we had to drop it and Mia was highly amused and forgave me at last.

It was around this time that my grandmother passed away, and Mia reacted badly to the news. I've often felt Mia and I, as a single mother and daughter combo, were almost umbilically linked, and as she witnessed my face crumpling with grief I saw its mirror image in hers. 'Does that mean she's under the ground like William's grandad?' she wailed.

'No,' I said emphatically, 'she's in heaven with God.’

It was at that point I decided Mia needed to go to Sunday school. I was a committed agnostic, however I reasoned that primitive minds need the consolation of faith. Mia attended Sunday school until the day she told me she intended to convert the other children to Buddhism. Then I decided enough was enough.

And now, what of this new grief? How am I holding up on this interminable flight to retrieve her body? Well, not so well.

The tears are a relief, and I don't really care that my face is swollen like a swollen thing. What's harder is that the least suggestion of pain and violence on the film I'm trying to watch brings horrific visions of Mia’s final moments into my head.

If you want advice about how to talk to someone in my place, avoid saying, ‘Don't read this article.’ Whatever it is could easily become compulsive reading material. If I hear that a negative comment has been made, my exhausted body once again becomes awash with adrenaline, or cortisone, or some other substance that feels incredibly damaging, and I'm again suffused in a clammy sweat . Anyway, I ended up inadvertently reading a description of that attack.

In case you've managed to avoid it, I'll spare you the details, but the images are playing in my brain. I was told by the police that Mia was unconscious after the first blow, but my brain refuses to believe that, and instead it plays and replays that ugly scene for me until my whole being seems to be swelling up with grief. Post-traumatic stress probably.

I'm fearful of what the days to come have in store. I know people in Australia and at home are confused, distressed and angry about Mia's death and looking to blame someone. If I seem to deny them the right to retreat into xenophobia, will they turn on me? Will the press start to dig about or make up things to hurt me? Who knows? I don't care as long as they don’t discredit my girl. The thought of that brings back the fits of sobbing.

And what of that consolation I knew my little girl needed? Maybe it's not just important for children after all. Maybe we all have a need for a belief system at a time like this.

And what do I choose to believe now, in this time of overwhelming need? I believe that I need to go on, first and foremost for Mia's sake and for the sake of others around me, particularly for my lovely partner Stewart who deserves so much more than this. He's already carried five coffins, bless him, and one was his own brother.

I also believe Mia is with me on this journey. She asked me to come over in our last phone call and I agreed I would, now here I am. I believe we will hold each other again one day, and that the many who are grieving for her now will be with her again one day too. We'll meet her again one day, sooner or later, in our own bright places full of love.